Whistle Beneath the Glass

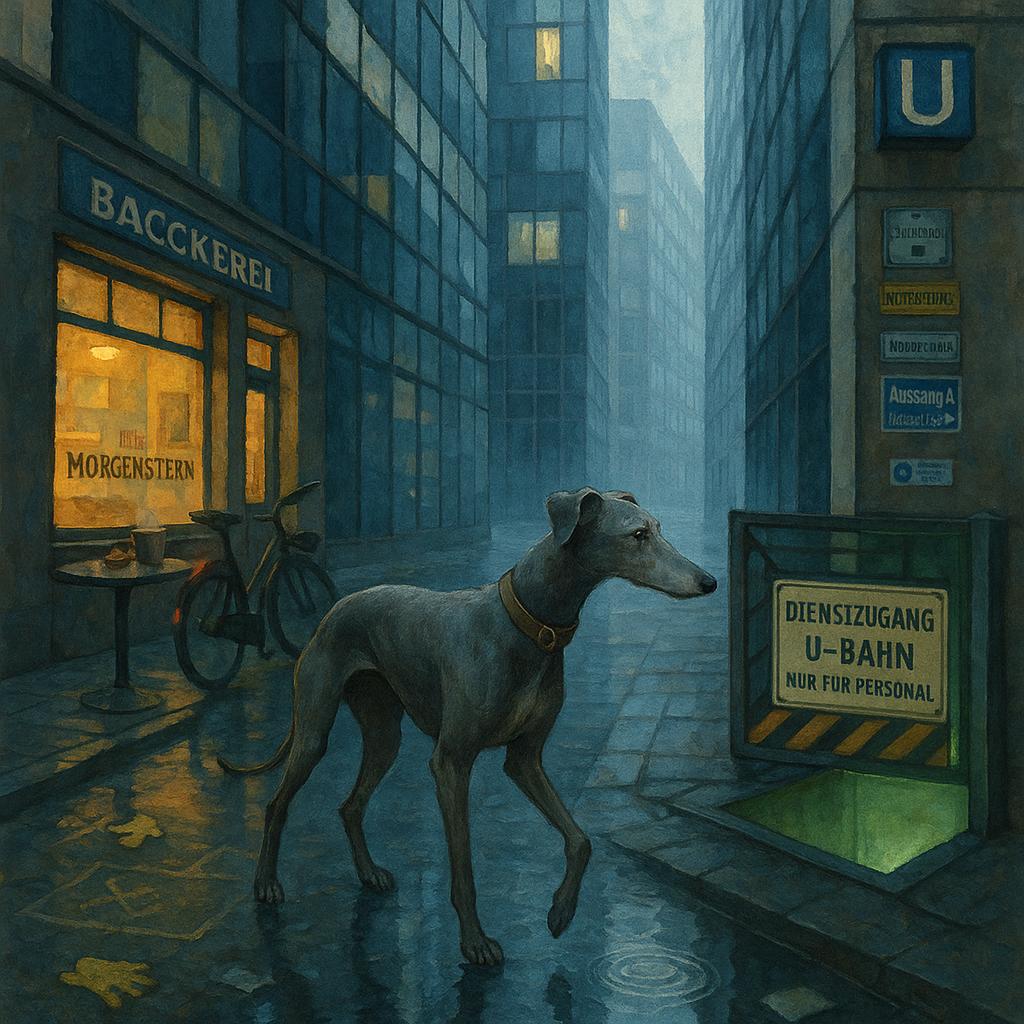

Within the glass canyons of the city, Kona, a fifteen year old greyhound, read the morning like a long story. The streets breathed coffee and rain and old fear. A courier rushed, counting debts. A child clutched a secret. From high windows, a widow forgave the night. Kona carried years in careful steps, each stride a memory of speed he could no longer spend.

Then the wind turned. It carried a single note, a whistle from the buried tracks, braided with the salt of panic. Far below, someone whispered help.

Kona slipped through the service gate as the street trembled.

The stairs were wet and the air tasted like pennies. Down where maps forgot to name things, the tremor became a hum, metal speaking to metal. Kona took the turns by scent and echo, shoulders grazing pipes, claws finding the seam of each step. His breath was a bellows. Old bones negotiated with the dark.

The whistle came again—single, thin, the sound of someone asking without words. It braided with salt and old oil and the sour cloth of fear. Kona followed it to the shuttered end of a maintenance spur where the tiles were older and the advertisements peeled in curls like fish skin.

She was there, a small knot of person behind a fallen grate, knee trapped under it. The flashlight on her wrist jittered a cone of light along the wall. She held a shoe box under her chin, as if it could keep her afloat. When she saw Kona, her breath hiccuped and the whistle slipped from her mouth and rang on the track.

“My mom is coming,” she said, but it wasn’t a promise. “I didn’t want to let him go up there. It’s cold.”

The box trembled. The lid was dragged sideways just enough for Kona to see the gleam of an eye and the busy whisper of feathers. The secret he had smelled upstairs: rooftop pigeon, soot-gray and ribboned at the ankle with a little blue string. A friend, most likely. A secret belongs to a pair.

The grate would not listen to his teeth. He pushed until his pads burned. Metal gave only the smallest sigh, a false hope. The girl tried to smile and failed. “It’s okay,” she told him, which is the thing children do when they need someone else to say it first.

Kona turned and ran.

Up through air that heated by the degree, through the door that fought and the gate that lied, he burst into rain bright enough to feel. He lunged back into the street’s current and found it full of faces drawing back in surprise. He barked, that old horn in his chest, barked until conversations snapped and phones paused, barked until the city listened.

The courier was the first to understand. Maybe because his counting had always been about weight, and this was a weight he could carry. Kona bit at his sleeve and pulled, then released, then ran three steps and looked back. The man swore, then followed.

From the fourth floor, the widow leaned on the sill, hair pinned with two crooked clips, the break of night softening on her face. She knew that whistle. Years of knowing it carried in her bones. Her husband’s badge lay in a drawer like a smooth stone, his keys hung against the kitchen wall for reasons she never explained to anyone. She reached them down from their nail and tossed the ring with an arm that remembered. It clanked on the hood of a parked car, skittered to the curb, landed at the courier’s foot. “Take them,” she called. “Blue tag, then brass.”

They ran: Kona leading, the courier behind, another set of footsteps joining—someone in a security jacket who had been nowhere and then was suddenly everywhere. The blue tag woke the gate. The brass spoke to the rusted lock in the lower door. Metal reconsidered. They descended into the throat of the city.

Water licked the edges of the tiles. The flashlight jittered like a moth. The courier took one end of the grate, the guard the other. Kona pressed his shoulder under the middle and pushed up with a grunt that sounded like ten winters. For a second the thing didn’t want to move. Then it did. The girl slid free, cradling the shoebox, gasping a word that might have been sorry or thank you or both. The guard hauled her to her feet. The courier steadied her and looked at Kona like someone seeing a treaty signed.

“Is he okay?” she whispered, touching the lid. Her teeth chattered. “He hates the rain.”

“Let’s see,” the courier said, hands already at his belt to strip off his jacket, to make a warm thing of it. “Let’s see him fly.”

They climbed back toward the color of day. Outside, the rain had softened to a fine cloth. The widow had come down to the stoop and stood with her keys in both hands as if she were counting them by touch. When the girl saw her she folded in, sob opened, and then the box opened too. The pigeon blinked once, shook grit from its wings, and rose. It cleaved the damp air like a letter folded at last and set on the right doorstep. Blue string flashed, a sign in miniature.

People clapped without deciding to, the way people do when something unselfish moves through them. The courier laughed once so hard it took a year off his face. Sirens sought an address and then lost interest. The city exhaled.

Kona lay down on the warm wavering pane of a steam grate and let the heat soak his belly. Hands found him—forehead to forehead, palms behind ear, a thank-you pressed into the muscle of his neck. Someone gave him half a cinnamon roll and he took it delicately and chewed it the way a good thing should be chewed. He could feel an old ache flowering at the hip, the debt of his push coming due, and it did not matter.

The girl knelt beside him, jacketed now, knee scraped, hair a damp wreath. “I heard you,” she said into his ear as if telling a secret back to itself. “I knew it was you.”

He watched the pigeon make three slow circles and find its line home. He felt the tremble under the street settle back into the hum that cities keep to reassure themselves. Above, high windows stared and blinked and forgave.

When they finally stood him, Kona rose careful as a priest lifting a candle. The pavement had the memory of sun under the rain. His person would worry and then forgive him for being where he needed to be. He took one long drink from a puddle that tasted of coins and clouds. The day unfolded its last pages.

He moved through the glass canyons with the quiet that comes after a race, not the silence of emptiness but the silence of a job done. He had spent a little of his saved speed and the morning had made good use of it. Around him, the city shuffled its pieces back into their ordinary places. The courier counted a new kind of number. The widow locked her door with the slow love of habit.

Kona carried years in careful steps, lighter by one. The wind turned again, but this time it carried laughter and pigeons and something like applause. He read the afternoon like a short ending, sure and clean, and when he reached his door he went in, the way a story goes quiet after its last, right line.