When the Tide Whispered My Name

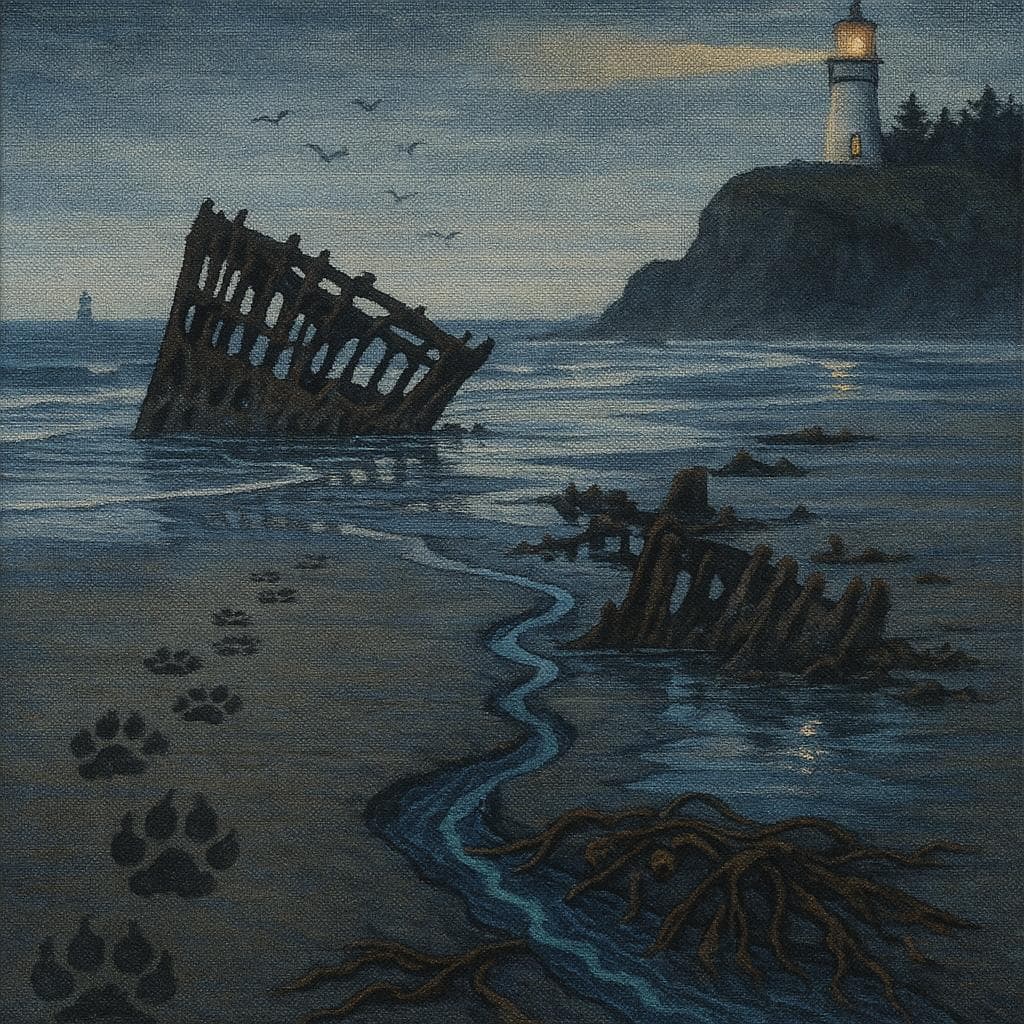

From the moment the tide began whispering in colors, I, Ivo, an old Istrian Shorthaired Hound of fourteen winters, knew the coast was remembering me. My paws draw maps on damp sand, every print a story I chased. Gulls stitch spells above. The lighthouse blinks like an eye, guiding me toward the wreck I dream about nightly. Salt tastes of figs and thunder. I hear a bell that no boat rings, coming from under the waves. Something waits beyond the kelp curtain. I step closer, muzzle trembling, when the shore beneath me cracks open and a voice says my name.

It says my name again, the way my first person did when I returned from thorn and thistle with blood on my ears and pride in my teeth: low, amused, sure. The shore splits like old bread. Inside is not darkness, but a steep of green light that smells of rope tar and nettles. Steps appear—scales of shell, stone worn smooth as a nose. My pads test them. They take me.

The kelp curtain breathes in and out. As I pass, tiny fish count my ribs and decide I am not food. Water climbs my legs, then my belly, and I expect cold, but it comes warm, the way summer stones hold day for the old. My hips stop complaining. The lighthouse blinks and the blink moves inside the water too, a slow pulse that leads, that says, here, here.

The bell hangs where the current keeps it honest. It is old and furry with salt, and yet when it calls, it is not metal but palm and voice and whistle. I hear the tongue of it lick the hollow space and what comes out is “Ivo” and “good dog” and the chuff of a laugh I chased for years. My tail betrays me and thumps the sea.

Beyond, the wreck waits the way a ribcage waits for breathing. Its planks have the same cracks as my paws. It was a blue boat once, chipped to truth. On its side I can still read the ghost of a name. Feral? Ferula? I press my muzzle to the letters and I smell pitch and anchovy and the wool cap of the boy who slept on deck with one arm over me. Luka. He tasted of cigarettes stolen from his uncle, he told stories to the net and to me, he whistled two notes that were an oath. The day thunder wore a coat of wind, his hands were quick until they weren’t. The rope sang a song called Breaking. The sea took his cap and then took him. I brought the cap to shore and worried it until it knew all my feelings. After, the coast spoke only in whistles and I learned to listen to emptiness.

The voice under the kelp is the same voice as he had when he pretended to scold me for stealing figs. It runs along the ribs of the wreck and through me, and every thorn of the old years falls out. “You came,” it says, as if there was anywhere else for me to go. The bell nods, proud of itself, and a string of bubbles climbs like a path.

We go—not with swimming, because there is no need now for the flailing rhythm of lungs and legs. We go the way scent goes, honest and straight. The water is full of old village tastes: iron of keys, smoke of olive wood, damp stone that has known knees. Bells from the hill church answer the bell below, and for a moment the whole coast hums with the voices of bells remembering their hands.

I find the cap again. It is not cloth now but a circle of light that fits between my ears without weight. I find his whistle, which turns, invisible, in the water and touches my chest in exactly the right place. “Bravo,” he says, the word a warm pomegranate he breaks open for me. I do not need eyes to see him. I know the shape of him by the way the world arranges itself around his absence. The world unclenches. He rubs the place between my brows where storms hurt, and it does not hurt.

The wreck shifts and becomes not an end but a house. I see it the way dogs see, not how men record it with pencil and ledger. There is a hearth where mullet fry in old oil. There is a doorway hung with drying nets that let in light and keep out the dull flies of sadness. Kelp is a curtain, yes, but also a fringe of grandmothers’ shawls. The bell is a clock that never tells me I am late. When he opens his palm, there is my bone from a winter that tasted like truffle and snow; there is the stick I carried for a whole summer until the bark polished to river; there is a small stone flat as a tongue that licked me when I was a pup. “You have carried so much,” the voice says. “Let me carry you.”

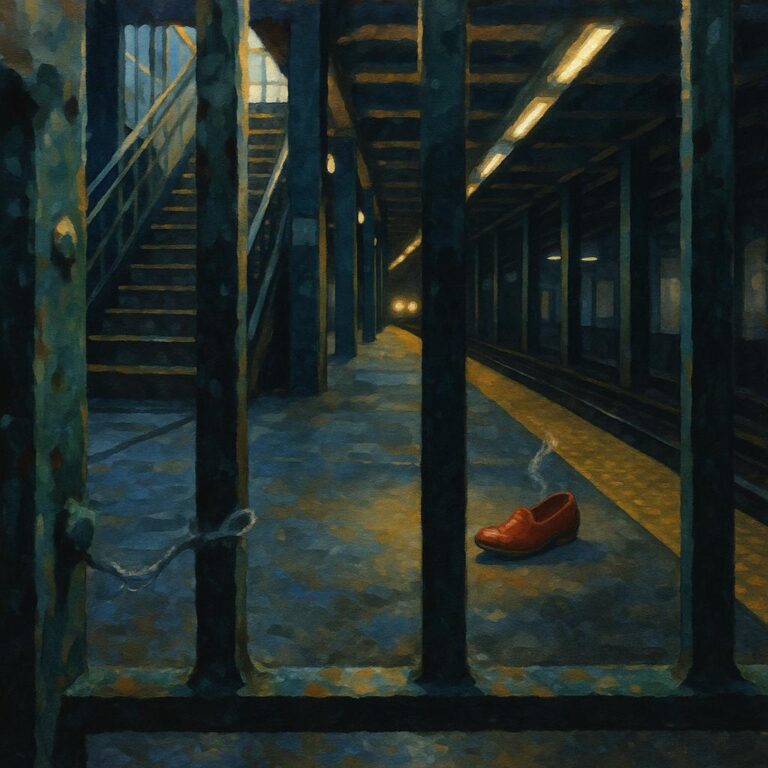

Above, the gulls are still scribbling. Their black-tipped pens write me into the margins of the sky. The lighthouse blinks—one, two, a heartbeat that does not miss. The crack in the shore sighs and closes, but not to shut me out. It holds a place for me as a warm bed holds a shape after I rise.

I curl where wood turns to sand turns to story. The sea, which is not a thief after all but a keeper of careful books, noses my paws into comfort and speaks names to me: jackalberry, juniper, sail, Luka, Ivo. Salt tastes less like thunder now and more like the tongues of puppies who do not know their own feet. The bell quiets. Not silent—the way salt is never flavorless—but resting.

My prints behind me fill with water and then with little fish who think they have found new homes. This pleases me. A dog likes to leave use behind him. On the path not yet wet, a child will find a line of tracks and hop from one to the next, and he will feel himself clever because he is following a dog he cannot see. He will whistle without knowing why and the tune will be the right one.

Gulls drop lower, throwing nets of shadow over the sand that do not catch me because I am not running anywhere anymore. I am where I was always going. The coast and I share a breath. I give it back, and it gives it back, and the world keeps that small exchange as if it mattered, which it does. The wave leans in, says my name a final time, softer, and I answer by putting my head down on the knee I have been looking for, the knee that smells of nettles and soap and all the good years, and in that easy place there are no more distances to cross.