Waffles and the Rat King

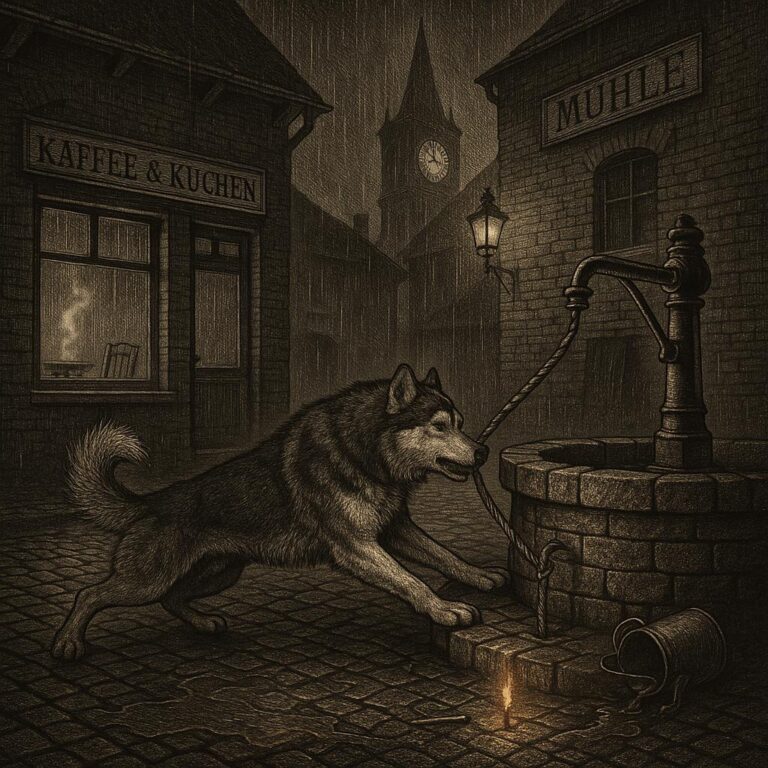

In the city that never naps, a fifteen year old Silken Windhound named Waffles ruled sidewalks with swagger. He knew every hot dog cart’s secrets, couriers‘ squeaky brakes, and which revolving doors tried to eat tails. Pigeons respected his seniority. His human, Mara, thought they were heading to the park; Waffles knew better. The scent of pretzels braided with the whisper of a lost squeaky toy tugged him toward the subway. Below, turnstiles clicked like castanets. He lifted a paw, judge and jester in his gaze. The train sighed open, and out stepped city’s infamous Rat King waving a churro.

He was shorter than legend but wore authority like cinnamon sugar. Churro held aloft, seven whiskers braided with foil, the Rat King bowed just enough to be protocol, just little enough to remain dangerous. Around his ankles, attendants rippled in a gray tide, their eyes bead-bright. The platform smelled of brake dust, old coffee, forgotten raincoats. Mara’s hand hovered at the leash clasp.

“That is not for you,” Waffles said with an eyebrow at the churro.

“It is for peace,” squeaked the King, and a sugar crystal fell like a snowflake. “And for a favor. Your nose for our tunnels for a relic of yours.”

The whisper of the lost squeaky toy tugged again, from down where trains howl and the city keeps its secrets. Waffles looked up at Mara. She met his gaze and nodded like someone pretending they understood what the dog was saying. She had always been a quick study.

He followed the Rat King along the yellow line until a service gate sighed open on hidden hinges. Rats poured through. Waffles folded his old legs and slid under, chest brushing grit, plume tail flagging dust. The light changed. The air went wet and metal, a soup of warm wires, old pennies, spilled mustard, the ghost of lilies from someone’s bouquet a year ago. The tunnels sighed and popped and spoke in their own impatient language.

“Your relic wedged our machine,” the King said, skittering along the edge. “It sings when it should be silent. It calls our children into gears. We tried to quiet it with churros, with lint, with fingernails. Our engineers are small.”

Waffles snorted; it echoed like a bass note. He remembered the toy—cheap plastic, duck yellow, a squeaker that squealed in the register of joy. Puppy afternoons returned in sudden, small increments: a couch he wasn’t allowed on, sunlight igniting dust in the air like constellations, Mara younger, clapping, saying, “Bring it, Waffles! Bring it!”

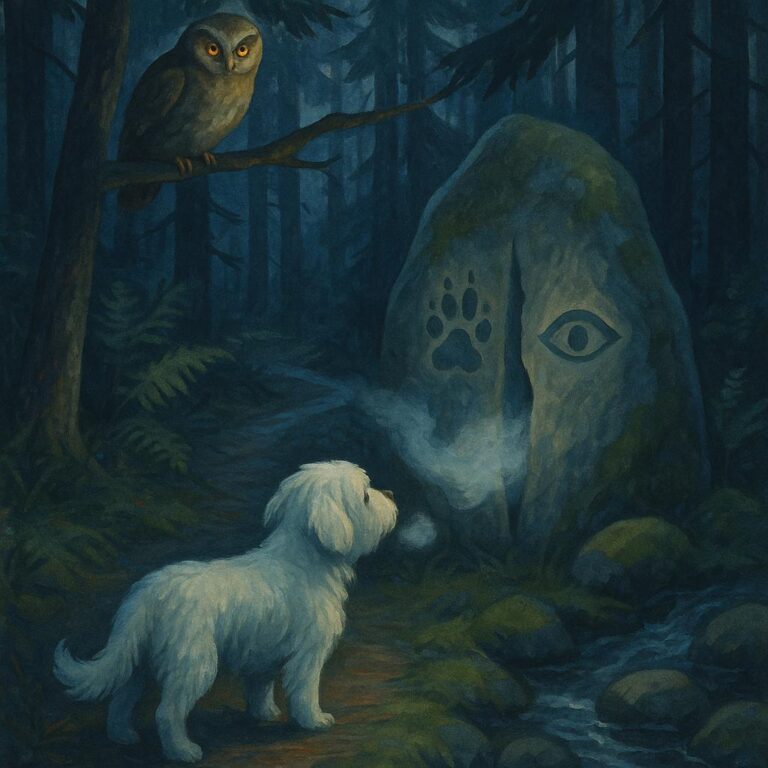

They came to the switch, a tangle of mechanical sinew stuttering with responsibility. The squeak was in there, a heartbeat in a throat. Around it were offerings: bottle caps, gum foil, a metro card that had run out of rides and been granted an altar’s afterlife.

Waffles tucked his paws beneath him and laid his chin against cold steel. This was a job for long muzzles and patient teeth. He breathed slow, counting by smells. Oil. Hot. Rat fur. He slid his snout into the labyrinth. The metal tasted like pennies and thunder. The squeak called again, higher, delirious. He closed gently around slick plastic, angled, waited, felt the machine shudder, and with an old dog’s stubbornness matched to a dancer’s memory, he didn’t pull yet. He waited for the slip in rhythm, the tiny pause between breath in and breath out of the city, then he drew back.

It came free with a gasp of released tension. The machine sighed, the rails sang truer, something large miles away decided not to have an argument with gravity today. The toy was scuffed, noble, ridiculous in his mouth. He delivered it to the platform of rats like a priest presenting a relic. It squeaked once, unasked, in a tone that could only be described as delighted profanity.

The Rat King flattened his whiskers in gratitude. “The truce, then,” he said, because Waffles had named his price before he knew he had. “Pigeons keep the mornings. We take the nights. Noon belongs to the messy children. We do not bite toes. They do not peck tails. The pretzels will be shared.”

“Also,” Waffles said around the toy, then put it down because diplomacy prefers consonants, “your nephews will stop chewing buskers’ amps.”

The King winced. “They thought the cords were snakes.”

“They are snakes that sing,” Waffles said. “Respect the musicians.”

It was all very simple after that because rules make cities possible. They climbed back, the rats slipping like shadow, Waffles awkward and heroic, toy in his jaws, his joints making small wood-sounding pops. The gate shut. The platform opened like a mouth to the day. Mara stood where he had left her, hands in pockets, pretending to ignore the fact she’d just watched her old dog broker a municipal treaty.

She knelt, and the years folded like napkins. “Is that—” Her voice caught on a little laugh. “You ridiculous thing, where did you find that?”

He set the toy in her hands. The squeak answered: under the couch, in a drawer, on a windowsill by the raven plant, fifteen years of classrooms and train rides and Tuesday nights.

“Park?” he asked with a look.

“Park,” she said, and that was law denied only by rain and revolutions.

They walked topside. Pigeons cooed like gossip over coffee. A courier braked, respectful, because the city remembered favors like a grandmother remembers recipes. Past the pretzel cart that flaked mercy on the wind, through revolving doors that backed down from their old grudge, into a slice of grass bordered by traffic and tiny wars, Waffles tested the toy’s voice. The squeak came out sticky with tunnel air and triumphant. He chased it two bounding strides, remembered his hips, chased it another half stride anyway because dignity is negotiable when happiness whistles.

Mara lay on the grass, hair a dark comma on green. He folded himself against her like a vintage coat. The toy rested between his paws, sentinel and souvenir. High above, a falcon put the fear of god into a gaggle of pigeons and then decided he had better places to be. Somewhere below, rats told a story about a dog who reached into the throat of the city and made it hum.

The sun pulled down the afternoon. The park salted itself with shadows. Waffles watched his kingdom arrange itself into evening: the kid learning to throw a frisbee and failing with such artistry that the frisbee was proud, the older man who always smelled like mint and old books, the couple arguing gently in two languages, both of them right.

He was the oldest of good boys, and he had work yet—checking hydrants for messages, auditing benches for napping grade, reminding a hot dog cart that hot dogs can roll—but the city that never naps cannot stop a dog from claiming a pocket of sleep. He placed his nose on his toy and closed his eyes.

Mara’s hand found his ear, traced the old map of it. The squeak, exhausted from its adventure, offered one last soft note that nestled into the murmuring larger song: trains, shoes, laughter, tires, leaves, lives. Waffles let the music hold him. The city took the next watch, and the sidewalks, for once, walked themselves.