Mara’s Red Shoe

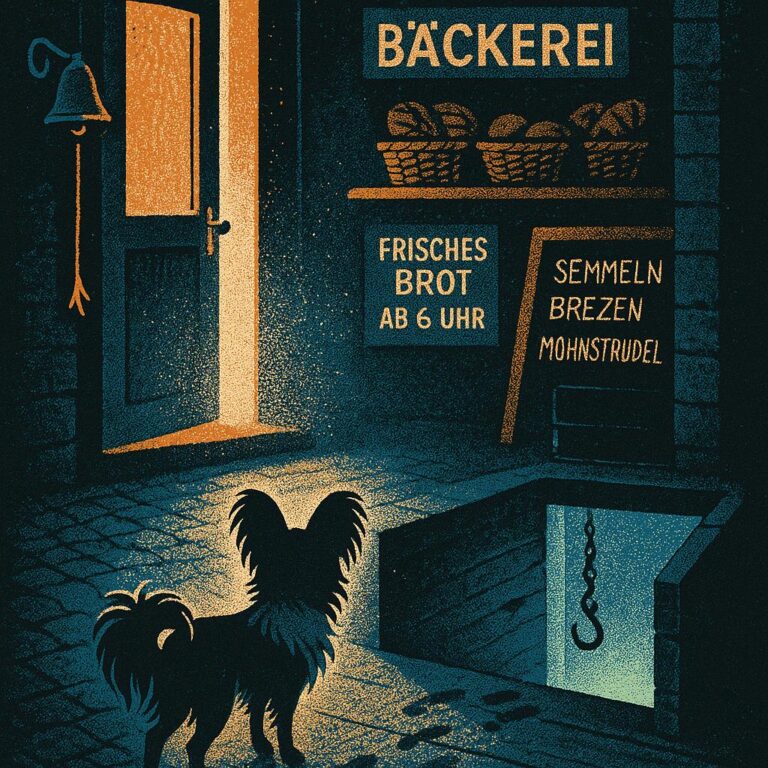

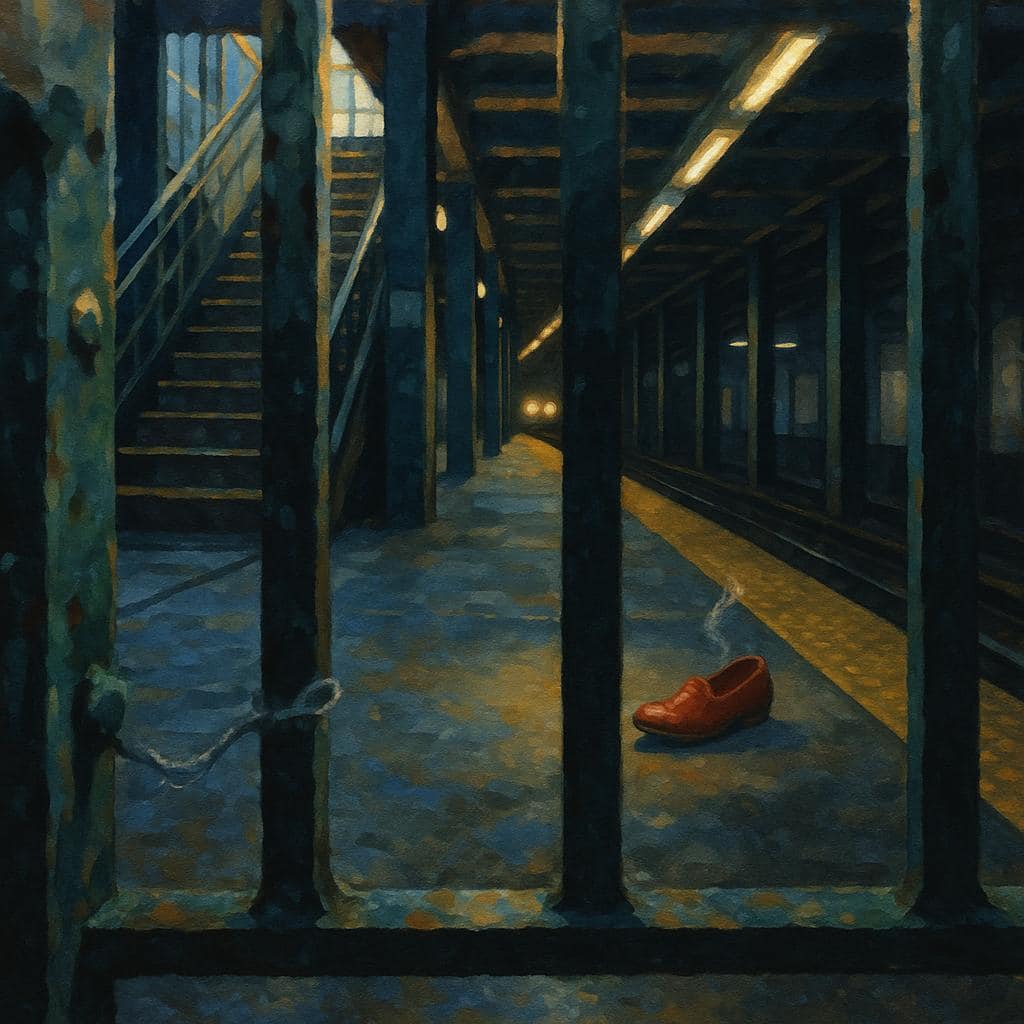

Gravel sings beneath my paws as dawn rinses the city glass. I am Gideon, a fourteen-year-old Glen of Imaal Terrier, more gray than ginger, yet my nose still maps avenues like veins. Humans hurry like thoughts; I travel beneath them, reading heat and oil. Today the air tastes wrong, metallic and sweet, like memory bleeding. Mara, my person, did not rise. Her coffee cooled, her phone kept buzzing. I traced her scarf’s ghost to the shuttered station. The platform shudders. A train howls from the tunnel, and on the rails ahead lies Mara’s red shoe, still warm.

The rails sing a thin wire note that raises my hackles. Hot wind pours out of the tunnel, tasting of dust and brake pads, and the platform breathes in and flattens. I know the rails’ voice; long ago, as a pup, I learned that the humming ones bite. I do not drop down. I press the yellow line with my chest and throw my bark into the black mouth.

Humans turn their faces, some laughing, because they hear noise and not meaning. The train shoulders the air. Its howl shears past and the red shoe flutters like a startled bird, spins, and ricochets into the trash-shadow under the overhang. Sparks crackle, and with them a bite of copper on my tongue. Then the howl thins, the tail wind licks my ears, and the rails quiet to a dull breath.

I jump.

Gravel teeth nip my pads. I keep my shoulder low, the way I hunted rats in barns, and snag the shoe by its strap. It is warm, Mara-warm—spice, soap, the thin floral of her lotion—plus the iron coin of blood and a sugar-rot I have only smelled when she slept too long and the room went stale. The shoe is talking fast. I climb with it clamped in my mouth, my old haunches burning, and land back on the platform with a grunt.

Mara’s scent is braided through the shoe, but it runs away from the lip of the rails, not toward them. I set it down, take one breath, and the thread leaps out, bright as a leash. Not toward the escalators, not across the floor like all the other foot-sweat and hot rubber. It goes right, to the metal door with the yellow stripe and the NO ENTRY block letters that mean nothing to dogs.

The crease below the door smells of oil, bleach, and mouse. I put my paw under and hook the rubber lip. My shoulders complain, the scar on my flank twangs, I shake my head as if a fly has landed between my eyes, and then the door hiccups. A hand has left it carelessly not-latched. A breath of air slips out, sweeter and wronger than the platform: memory bleeding.

I shove in sideways, my ribs making a squeak against the metal. Inside is a throat of concrete, lit with a drip-drip of yellow bulbs. The lights buzz in a way only teeth hear. The scent of Mara spills down the hall like a dropped spool. I follow, claws skittering, past a rattle of mop buckets and the stale-fur of a security jacket hung on a peg.

Her scent doubles back, staggers, smears. There, on the wall: a red thumbprint. Beneath it, a scuff of red leather. My heart thumps a heavy, old drum. The sweetness in the air is bigger here. Fruity, like the breath of apples going soft in a bowl. I have nudged Mara awake from this scent before, when she melted into the couch and her fingers grew slow. There is another smell laid over it now: a stranger—a wool coat that did not know our apartment, a cologne that tries to be pine and ends up sharp and false, the vinegar edge of fear-sweat. He was close to her. He touched the shoe.

I push on until the hall opens to a maze of pallets and pipes. The city’s intestines. My nails click on metal grates. There, behind a stack of paint buckets, is the soft thud of a breath that does not keep time right.

Mara.

She is on her side, her hair spread like riverweed, her face the white of the underbelly. One foot bare, the other still shod; the strap on its twin must have given, must have leapt like a red fish to the tracks. Her cheek wears a thin scrape, the kind a wall gives when you argue with it. Her mouth is open a little, and the sweet is pouring out. Her eyes are not here. I press my nose into her palm. It is cool, then warm where the veins run. The pulse is a small mule under the skin, stubborn. Relief and fear tangle.

I lick her hand, lick the sticky iron at her temple until it shines, press my forehead to hers, and then I leave her. The leaving hurts. My paws don’t want to go. But help lives where keys jingle.

Back through the throat, my teeth locked gently on the red shoe so the world understands what I am saying. Back onto the platform where the crowd has thickened into reeds. I do not waste a bark on everyone. I choose the man with the square blue shirt and the braid of plastic cards on his belt. His shoes smell like the room I just left.

I thump the shoe into his shin, bark once—and not a pretty bark. The one that drills. He looks down. His eyes flick to the shoe, to me, to the yellow-striped door I came from, cracked like a mouth. I run to it and back. He follows. He is smart enough to listen to a noise and hear meaning.

His hand shakes keys at the door. The lock opens with a metal cough. We enter. I lead. He is slower than me, but his feet make a command kind of sound that tells others—as they appear, more blue shirts, a woman with a walkie—that here is something to move for. The lights buzz like angry bees.

We find her. The blue shirt man kneels, says Mara’s name in a careful way, like he is laying down a glass. He touches her neck where I did and calls words into the walkie that bounce and split and come back as boots, a package that smells like plastic and sterile lemon, hands in gloves that snap like flagpoles in wind.

“Hypo,” says one of the lemon-hands. “No, look—fruity—get the glucagon ready. And that head. Easy.”

Their voices make a rope over us. A needle whispers into Mara’s thigh. Her breath takes a hitch and then a different shape, less shallow, more like the tide I know. Her eyelids tremble. She blinks and swallows and swears—softly, a little, the way she does when she finds an email from her boss at midnight.

“Gid?” Her voice is a pebble dropped into a pond.

I put my head under her fingers. The fingers remember me before the eyes do; they latch onto the thick of my neck, into the wiry scruff that has caught a thousand burrs. Her hand smells like fear and then changing to relief. The sweetness fades minute by minute, replaced by salt and the small chemical that means she is sweating now because she is coming back.

They put a white hat of bandage on her temple. They slide her onto a board and strap her with belts that smell like new tires. I argue about the belts with a whine until she chuffs a laugh and tells me, “It’s okay,” which is not about belts but about everything.

We move. The station becomes a funnel. The elevator is a box that has swallowed many of my mornings; today it swallows all of us at once. The doors open to street, and afternoon has crept up without asking. Siren-light paints rainbows on the bus windows across the way. The ambulance smells like every clinic, every sharp citrus and rubbed-alcohol. I dislike sirens. They make my teeth itch. I plant my weight. A lemon-hand looks at me and then at Mara, who has my name in her mouth again, like you would hold a coin you want to keep.

“He’s coming,” she says. “He’s service.”

I am not, not in the way they mean, but I am service of the oldest kind. The lemon-hand nods. A space opens. My claws click on the metal step. The ride buckles and darts. I plant my feet and press my shoulder against the hard box that holds Mara. Her fingers find my ear and live there.

The city unwraps outside in red stutters. Inside, the air is a clean slice. I watch Mara’s chest rise and fall. I count with my nose, because numbers for me are smells: the rubbery whiff each time the bag collapses, the starch of the cotton, the electric ghost of the defibrillator no one uses. I check the corners of the ambulance for the stranger’s pine-false cologne, and it isn’t here. His scent veered off at the service hall’s cross, a quick left scrambling into nothing, into the crowd. I have teeth left, if he ever finds my street again.

At the hospital door, they try to divide us. They put a line of light on the floor and say stay. I sit on the line. They wheel her through a mouth that eats families and spits out discharge papers. Someone with a clipboard asks me a question about ownership. I look at them until they look away.

Time falls into a bowl and keeps rolling. The bowl is a chair with cloth that smells of other dogs waiting to be let in, of tired and patience and vending machine oranges. My hips ache and my eyes grow heavy, but when the automatic doors inhale and exhale, my head lifts each time, because any breath could be her.

The doors open and there she is, upright, wrapped in hospital cotton and a cheap blanket that sheds blue fuzz, a small, stubborn smile taped to her face with the same stuff holding the bandage on. A nurse steers her by the elbow like she is a shopping cart with a squeaky wheel.

Mara crouches. Her hospital bracelet rattles. I fit my head to the crook of her arm, into the hollow I was made for.

“You nosy old man,” she says into my ear. “You absolute hero. I lost my shoe.”

I press the salvaged red into her lap. It is scuffed, the leather nicked, but it has kept its color. She laughs—really laughs now, the laugh that tugs her shoulder blades close together—and then she cries the way people cry when they stop running but the heart is still moving fast. I let the crying wet my head. It smells like salt and new grass. It is a careful thing. I am careful with it.

We walk home that evening slower than the city wants, her arm looped through the strap of my harness. Sidewalks flex under us. Neon opens its flowers. The wrong sweetness has left the air; instead there is crushing basil from a pizza place, hot metal from a bus, rain sleeping in somebody’s tires. People pass and look down and up again. Some of them see us. Some just see their own feet.

Our door opens to the apartment where the coffee sits in its cold ring. I drink the water she sets out, and she drinks juice that smells like oranges and medicine. She eats the small square that crinkles in foil. She sits in the chair that has learned her shape and closes her eyes, but only for a breath. When she opens them, I am watching. The room is no longer stale. It is ours again.

She takes my face in her hands. Her thumbs smooth my eyebrows, my white lashes. She rests her forehead against mine, and our breaths make a tent between us. Her heartbeat is steady, a familiar drum. I tap my tail against the floor in time, then just a little faster, because I am greedy for this.

Outside, the city lays down its evening. I lay down as well, my bones grateful to be bones. The day has been long, but my job is simple: find, keep, return. I sleep with one ear up, as I have always done, listening for the shape of her name in the dark. When dawn comes to rinse the glass again, I will take her to her coffee and to her train, and I will keep mapping the veins of this city until the song of it grows too quiet to hear.

For now, she is here. My nose says so. My paws stop their worrying. The gravel of the day has finished singing.