Whistle Across the Current

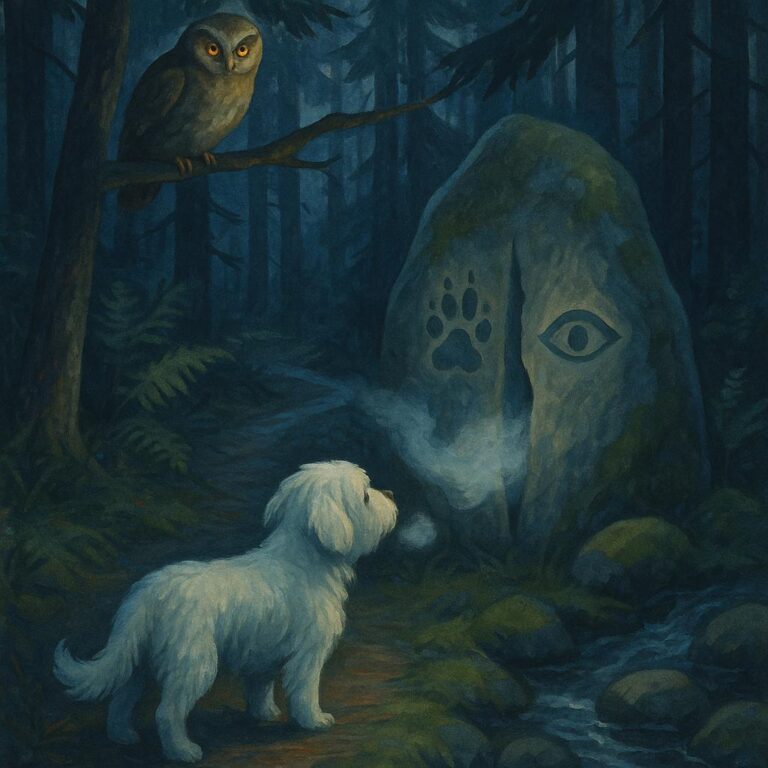

Her whiskers trembled as Fleur, a fifteen year old Papillon, watched moonlight braid the river. Roses perfumed the air; she remembered Beau’s gentle evenings. Then a familiar whistle drifted across the current. Heart quickening, she crept closer, paws sliding as the bank suddenly gave way.

Part 2:

Cold seized her belly as the earth let go. The river lifted her like a sheet shaken open, and she went under once, twice, ears slicked to her skull, lungs burning with the shock of silt and stars.

Instinct found her before fear did. Paws churned, small and steady, the way they had in summer creeks when she was all spring and laughter. The current tugged at her spine; stones rolled under her pads as if the whole river were purring. Above, the moon wrote thin silver ladders across the black water, and somewhere, clear as a bell and older than sleep, the whistle came again.

Two notes. The ones that meant come home.

She angled her body toward it. The smell of roses thinned, replaced by iron and reed and the dark, clean cold. She heard him before she saw him—boots scraping, cane striking root, his breath tight with calling her name into the wet night. Then Beau was there on the low shelf of gravel, hat pushed back, coat already in his hands, sleeve dragged long to reach. He whistled, then lowered his voice to that place she could always find. “Par ici, ma belle. That’s it. Good girl. Come.”

Her legs shook; the current pressed. She aimed for the pale of his hand. Water rang in her ears. For a moment she felt her age—fifteen winters, fifteen summers of climbing the same back steps, of finding sun-squares on old rugs—but the sound of him unspooled something stronger than tiredness. She kicked. She slid sideways. She coughed river and tried again.

Beau stepped into the water until it caught him at the shins, then the knees. He hissed at the cold and laughed at himself in the same breath. “Ah, foolish old man,” he said, and made a bridge of his coat, a dark raft across the black, the wool blooming with water. “Take it, little butterfly. Bite and hold.”

She bit. His knuckles closed over the collar he had buckled that morning with those careful hands. The river pulled hard, but he pulled harder, gasping, slipping, catching on a buried root. Then she was on the gravel, coughing and bright with it, and he was on his knees with her pressed to his chest. Everything smelled like him—woodsmoke and apples and the faint ghost of rosemary from the garden, and beneath it all the warm animal truth of home.

He wrapped her, muttering soft nonsense, words she did not need to understand to know. “You stubborn star. You brave thing. I’ve got you. I’ve got you.”

They climbed the path together, his arm firm under her ribs, the night’s wet shaken from the roses in passing to anoint them both. In the kitchen the lamp pooled honey on the table. He rubbed her down with the good towel, the one that had dried a hundred rains, and set her on the old braided rug. Heat from the stove found her bones. He hung the whistle on its nail by the door and touched it with two fingers the way some men touch saints.

Fleur’s breathing smoothed. She dreamed the river less sharp, softer around the edges, as if the moon herself had come down to comb its hair. Beau made tea. He moved her bed closer to the fire. When he sat, she shifted so her chin found the groove above his boot, the place long carved by evenings like this. He reached down without looking and rested his hand between her ears. The kettle sang. The house settled.

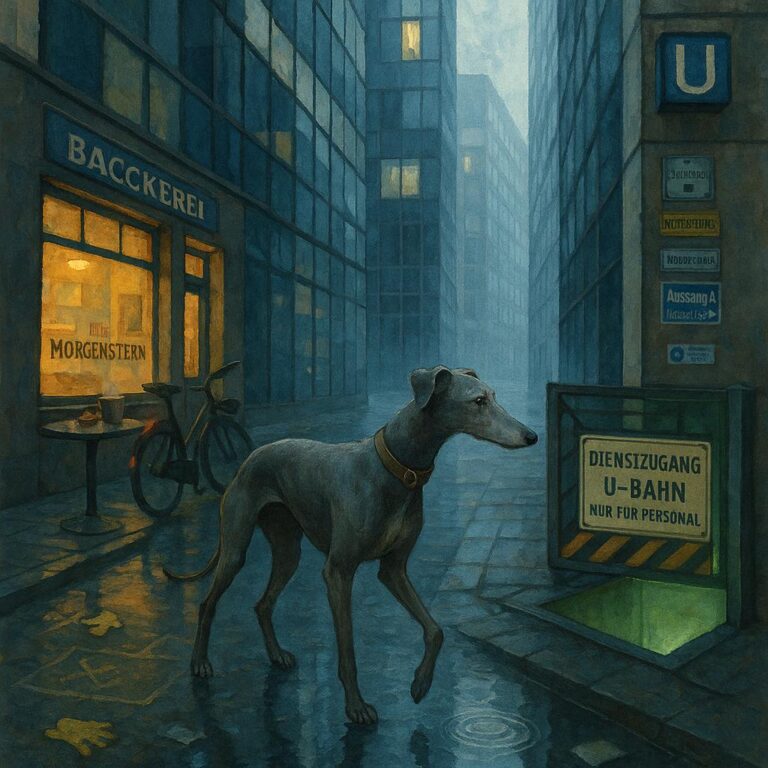

Morning found them slow and whole. Mist lifted off the water like breath. Bees stitched among the roses, their work neat and secret. Beau tossed bread to the carp and whistled to no one in particular, a whisper of habit in the bright air. Fleur went only as far as the warm step and lay where the sun could collect her.

Later, when shadows lengthened and the river braided itself in silver again, another whistle drifted across the current—from a boy on the far path, from a train down the valley, from the way sound carries at dusk and makes memory out of distance. Fleur lifted her head. Her ears, those little wings, turned.

But she did not rise to the edge. She did not test the bank. She knew the call and the answer better now. She turned instead and pressed her muzzle into the cloth at Beau’s knee. His hand, old and sure, found its place on her neck.

Moonlight would braid the river again and again, roses would keep perfuming the air, and whistles would wander the evening. When they did, they would find Fleur safe on the warm bank, heartbeat measured to Beau’s, as in all their gentle evenings, home.