Whispers Beneath the Altar

In the wind scoured cloister, Eusebio, a fifteen year old Estrela Mountain Dog, raised his muzzle to the bells. He remembered snow on shepherd trails and the taste of wolf breath, but here the stones hummed with vows. The monks feared the night thief; the abbot feared his doubt; Eusebio feared forgetting the path home. Candle smoke curled into symbols he alone could read. It led him past the scriptorium to the sealed crypt. Beneath the altar, a heartbeat answered the bells. The slab shifted, cold air pressing his whiskers, and from the dark a voice whispered his true name:

—not the kennel name the monks had given him, but the braid of scents that was his first knowledge: lanolin and milk, iron of snow at dawn, the vinegar sweat of the young shepherd he’d shadowed, the musky rune of wolves threading the pines. It spoke in pulse and frost, and he stepped down into it as if back onto the old trail.

The crypt air was damp, green with stone and old beeswax. In niches lay kings of parchment and bone; above them, the reliquary heart ticked under silver like a small bird trapped under a bell. Its beat was not steady—more of a call, a missing step in a dance. Eusebio nosed the seam of the slab with the caution of age, laying his chest against it, listening. The voice was there, under his ear, beside the heart, beneath all of it. Do not use your teeth, it told him, and the warning smelled like thyme and lamb’s ear and the crease in his mother’s paw.

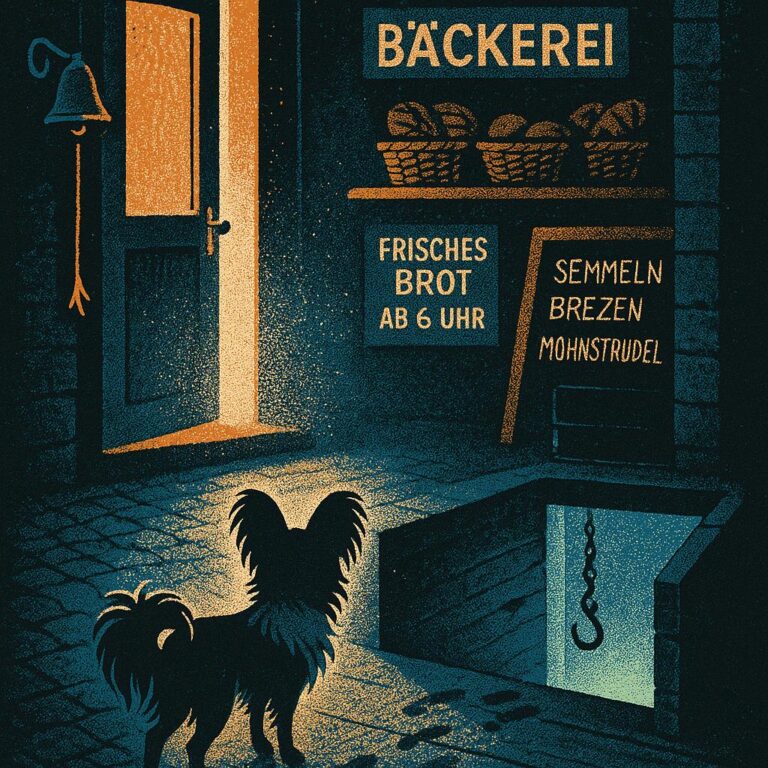

The bells hushed on their ropes. Their last tremor ran along the stones into his bones. Silence pressed, and with it the newest scent: lard smoke, wet wool, a boy’s fear grained with hunger. A thin hand in the dark. Metal scraped. A figure unpeeled from the shadow at the grate like a snake shedding its night: reed-boned, barefoot, eyes used to not being seen. The sack he carried was as big as his ribs.

Eusebio rose.

He filled the crypt mouth with the old mountain, with his chest and shoulders and the weight that had once turned wolves aside at a canyon lip. The boy stopped, knife in his fist pointed at the floor; a silly blade, thin, more tool than weapon. For a heartbeat that matched the little one under silver, they watched one another, both of them in the same pool of cool.

The boy didn’t smell evil. He smelled of raw turnips, of ash, of the river’s reeds where a person might hide from village lanterns. Under that, a thread: the abbot’s linen and beeswax. A visiting nephew, then, or some child of the launderer, or simply a child.

The world tilted; Eusebio swayed. The voice steadied him, his real name uncoiling in his chest like a long-remembered road. Not with your teeth. With your holding.

He stepped forward without sound, put his great head under the boy’s wrist, and lifted until the knife scraped against the plaster of the arch and fell into the old dust. The boy flinched like a hare. Eusebio took his sleeve and held it—not biting flesh, but the cloth—and turned, drawing him, not unlike the slow pushing of ewes across a stream when spring is too eager. He chose a path that curved away from the altar, up past the cold of old saints, toward the warm curling smoke where men slept and the milk pail clanged. His claws ticked on the chisels of the steps. The boy came because to resist would have been to fight a cliff.

Brother Mateo woke first at the sound, stumbling with eyes grainy and hair skewed, his mouth already forming the word thief. Eusebio set the boy down in a smear of moonlight in the cloister and stood over him, vast and simple.

The monastery came all at once like rain: torches, feet, a chorus of breath. The boy’s chest fluttered like the heart under silver. Eusebio lowered his head until his muzzle and the boy’s stomach were one rise and fall.

Then the abbot came, barefoot, habit loose, his face naked with the thing he feared. He had not put on his doubt like he did his ring and cane; it shone anyway, making him look both old and very young. He saw the knife on the steps and the sack, saw the beloved old dog, his champion and worry, saw the boy.

Eusebio’s eyes found his, and the abbot’s mouth closed on the word he’d come to use too easily: judgment. He let go instead. He knelt, and the stone bit his knee through fabric, and he reached out not for the blade or the sack, but for the thin wrist Eusebio had carried. Warm. Trembling.

Bread, he said, not to excuse, but to name the shape in the dark that had been stealing their cheese and apples and fat. He looked up at Brother Mateo, at the brothers behind him, at the fear that had made them whisper of ghosts and devils and thieves. The abbot, who had feared he’d misplaced God somewhere between chant and tally, found a better place to set his hand. We have plenty, he said, and his voice was almost laughing and almost breaking. The words went around the cloister and shook dust off the old frescoes.

They fed the boy at the refectory table with the big dent from the time the cask fell. He ate without taking his eyes off Eusebio until the hunger inside him believed the promise outside him. Brother Mateo’s temper found a stool and sat down. The abbot’s doubt folded itself small and settled under his scapular with the memory that there was always more bread when there needed to be, even in years when there shouldn’t be. Eusebio stood in the doorway while the brothers asked the boy his name and he mouthed it as if it were a poor fish and the bone stuck in his throat.

When dawn loosened its first thread over the ridge, Eusebio went back down to the church alone. The crypt mouth yawned as before. The reliquary heart ticked clean now, regular, as if reassured. He lay with his chest against the stone and felt it answer him, not like a bird trapped now but like a bird at rest in its nest, turning now and then to tuck its head under its wing.

Tired took him like snow takes a trail—slow, inevitable, softening the edges. The monastery stirred above: the scrape of benches, a cough, the stone basin’s cough of water. He could go when he pleased. He knew the path again: across the kitchen yard where sage grows wild and the cat pretends not to care, out past the gate the pilgrims smear with thumbs, over the shepherd track where the scent of the mother ewe he’d once chased still lives in the earth if you know where to put your nose. The mountain was an old song in his bones calling him to finish the verse.

He rose once more. His hips clicked like rosary beads. He took the long route through the cloister, each arch a memory: the novice who brought him bowls of broth, the winter he slept on Sister Imaculata’s cloak when she forgot it on the bench, the night he howled when the wolves came too close and the bells answered back that they had heard. The abbot found him at the gate, laid a hand on his flank, not to keep him, not to send him, only to testify. The hand trembled. Eusebio leaned the weight of a full dog life into it, then away.

The morning was clear. Above the olives, the ridge-line wore its old white cap. He did not hurry. He took his time with the thyme, with the burrs that clung and the places he had, once, marked as his with a young dog’s insistence. He found, as the path narrowed, that it didn’t matter whether he went out beyond the last milking stone or only as far as the rosemary bush that pressed against the outer wall and hid crickets. Home was a rope he had carried the whole time hooked to the ring of his true name, and he tugged on it now, and it tugged back, and the two ends met.

He lay in the sun on the warm cobble just outside the gate, head between his paws, facing the mountain. The bells began again behind him, first small, then filling. Beneath the altar the heart went on, untroubled. In the refectory a boy who had meant to be a thief wiped a heel of bread through a bowl and planned the planting of turnips in a patch the brothers would let him have. The abbot, whose doubt had found a seat, smiled into the morning and began his prayer not as a duty but as an answer.

Eusebio listened until the bells were not bells but snow geese, until the heartbeat under the stone was not a relic but the murmur of ewes behind a low wall. Scent rose like script again—milk, lanolin, pine smoke, wolf—and all of it spelled the same thing. He closed his eyes, not from fear of forgetting, but because he remembered so well he could walk the whole way without them. He let his name lead. He went home.