When the Reliquary Breathes

Across the cloister stones, my paws remembered every echo. I am Pax, a Pharaoh Hound, fifteen winters old, keeper of the night watch. The monks have gone, but the incense still clings to the corridors like a whisper. I follow a scent I have not met since puppyhood, a reed-sweet trail that winds toward the crypt. Candles gutter as I pass. The abbey bell shivers once. From behind the reliquary, mortar flakes. A seam of darkness shows. Something inside exhales my name. I press my nose to the crack, and a golden eye opens.

I do not bark. The stone breath tastes of lime and old beeswax. Dust powders my nose; it clings to whiskers and the tender web between my toes. The crack is narrow, more thought than door. I press my skull against it anyway, the bones that have learned bells and winter and rain. Once, when I was small and my ears were too big for my head, a novice pulled me back from this seam, laughing but stern, scolding in a voice that smelled of bread. Not yet, little one, not yet.

Now there is no one to pull. The mortar flakes soft as ash. The golden eye watches me without blinking. It is not a cat’s eye or a rat’s. It is my color when I run at dusk, the light that catches a hare just before it leaps. It is a patient eye.

I push. Stone whispers over my ribs. I stand in a space that remembers rush mats and winter water. The air is cool and full of reed-sweet, that green music from far banks. My paws touch flagstone, but something beneath is moving, slow as a sleeping flank. The candles above the crack are behind me now; their light does not follow. I do not need it. I see by smell and by the hair along my back.

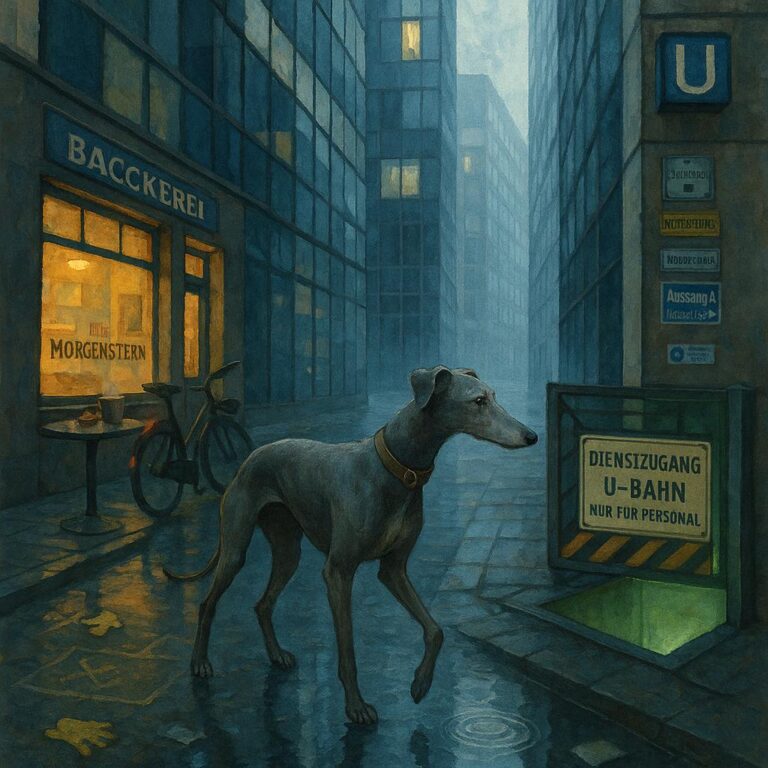

He is there. The long one. He is shaped as I am shaped when I hold myself still, when I become a reed in the wind. Tall ears, narrow face, the slope of the back that speaks of distance. His fur is not fur but something older—soot, night river, old paint. The eye gleams. One, gold as honey; the other a soft cloudy pearl. He exhales my name and the hair in my ears stirs. Pax. Scent says more than sound: tar of boats, sun-baked clay, hot skin of men who pray differently under the same sky.

We circle once, a polite hello that is older than abbeys. He dips his head to my scarred shoulder. I offer him my gray muzzle, my chest where my heart has beat too strongly on certain storms. We breathe each other. He smells of when dogs first consented to keep fire, of fish laid on reeds, of loaded donkeys stamping at dusk. I smell to him, I think, of bells and smoke and old wood, of wool and rain and the sweetness of spilled beer.

There is work.

He turns and the dark under the stones opens into a path where there is no room for a path. We go. His paws make no sound. Mine whisper salt, salt, old salt, across the damp. The reed-sweet grows stronger, and with it rise other threads, thin as hair, each with a name. Brother Aimo, who limped. Father Bede’s ink-stained fingers. The girl who carried milk when the fields still sent girls, who fed me crusts for a week until someone told her kitchen dogs are not for petting. The plague year when the mule wouldn’t pass the gate. Voices that don’t have voices, but I know them because I am keeper and nothing kept is only stone.

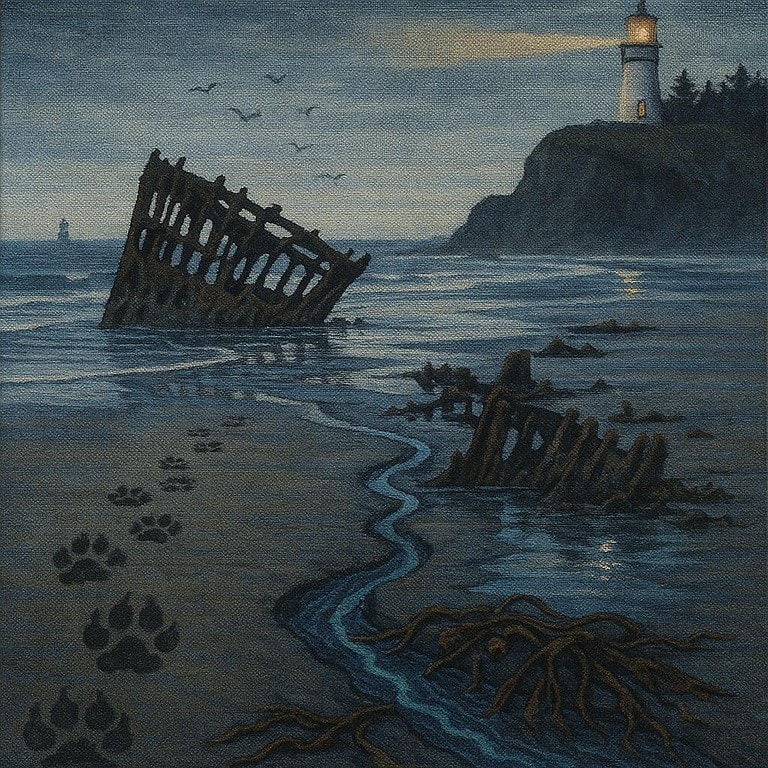

We come to the pool that is not a pool. Stone shows water and water shows sky and the sky is full of little fires you can’t chase. A boat waits in it. Not boat—hull and curve like a rib, smelling of pine and pitch, old but not rotten, so clean it makes my nose sting. At its prow a painted eye watches forward. It is not the golden eye, which is alongside me now. Two eyes watch; none blink.

He steps onto the boat as if stepping onto a fallen trunk. I do not let water have me when I don’t know its tricks, but this water smells of sleep and linen and the pages of books closed with a sigh. I trust it. I jump and land without splash. The boat breathes; we breathe.

The river under the abbey carries us where night collects the old light. Along its banks—if banks they are—hang tatters of habit cloth, the wool and sweat of prayer. Names written into wood with knives, then smoothed away by time, float past and return. The monks once taught me to sit; I taught them how to keep the fox out of the hens without anger. All lessons are scent; they do not go.

He looks at me and does not speak. He touches the side of the boat with his paw and the reed-sweet deepens. From the dark come other shapes. They are not men, nor only men. They are the warmth left on stones where men knelt. They are the dry crackle of pages turned. They are the thrum of the bell in my bones on winter nights when the wind took our roof and we tied it down with ropes, three of us, one of me. They are the last breath of Brother Aimo when he smiled at the far wall and said, Hush, Pax, it’s fine now, and I let my head lie on his chest even after the chest forgot to move.

Come, I tell them in the way of dogs, with tail and shoulder and the set of my head. Come, this way, stay together. We will not go fast. There is time enough in this dark to be slow. They gather, obedient as wheat in wind, and fall in behind us, a line of things-that-were that have forgotten how to find the door.

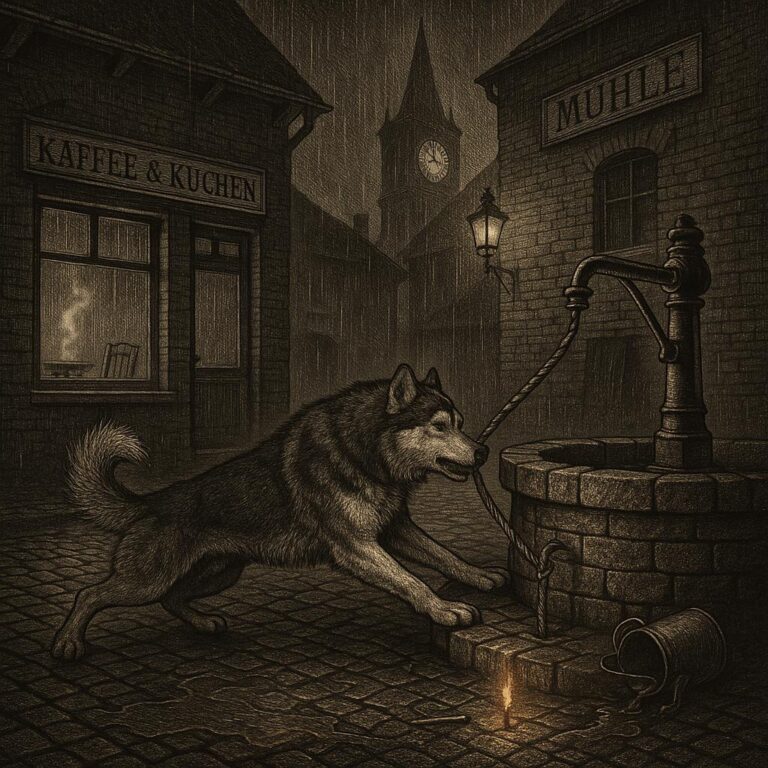

We come where the river under the stones meets the bell. It hangs like a ripe fruit above us, its brass skin smelling of cold and many hands. The rope falls to the water and trails a tail like mine. I have never been allowed to hold this rope. My teeth itch with wanting. The first time I came near, a stern palm blocked my nose. Not for dogs, Pax. Not yet.

I catch it now. My jaw complains. The rope tastes of dust and oil and the salt of skin. I pull. Old muscle pulls with me, young muscle remembering how. The bell moves once, unwilling, surprise in its belly. I pull again. He beside me sets his paw on the boat’s gunwale, not to help or to hinder, only to say yes. I pull a third time and the bell finds its own wanting.

The sound rolls through stone and water and me. I feel it in the soft gap where my ribs meet, under my tongue, in the tender place where ear joins skull. It is low and clean and full of both wheat and bone. The line behind us stirs. Things-that-were lift their faces as if to catch rain. The reed-sweet rises like a pot coming to the boil. The river moves away from the bell and toward a gate I have patrolled since I learned my name.

The cloister door stands where it always stands, only we have come to it from within, like a mole finding day. It is unbarred. I step out on the familiar stone. The sky above the cloister is night, and in that night a fox coughs and a star falls and the world does its work without me. I lead them along the walk, past the place where Brother Bede’s cart ran a groove I know even in ice. Past the kitchen door whose hinge I have thumped with my flank every morning. Past my rug.

The orchard is black with apples. The trees wait, slick with dew. Beyond their low fence the field breathes out its good dark earth. The line behind me streams like smoke, like leaves when wind wants to clean the ground. At the gate I step aside. This is what dogs do. They find, they show. They do not hurl.

They pass. One by one. The warmth of kneeling. The smell of wet wool. The scratch of quill. The print of hands on stone. The last to go is a laugh—a small quick thing that I could not chase when it lived because no one thought to throw it for me. It darts and then its tail touches my nose and it is gone. The orchard takes what is owed. The gate breathes and is only wood.

I am tired. The boat has gone. The long one is with me still. He looks at me with the gold eye and the cloudy one and he nods, which is a dog’s way and a man’s too when words are not enough. He leans and touches the hollow between my eyes with his nose. It is cold, like water on a hot day. He smells of ash and honey and the far quarries where stone is cut into sky. He turns toward the crack that is door that is seam and pauses. He does not command. He is without command. He is a path.

Not yet, I tell him with my ears. Not quite. There is a place where the mice come to check the floor for crumbs. There is a rug that holds my shape. There is a spot in the refectory where morning finds me and gives me a square of sun, small but perfect, that moves as the world moves and asks nothing.

He waits while I make the rounds once more, slow, my old toes clicking like rain. I nose the kitchen door and listen to the absent pots, the sleep of hooks. I walk the nave and touch my shoulder to the pew that holds Brother Aimo’s dent. At the font I drink, not because I am thirsty but because it is cold and it is there. I set my chin on the slab of the sacristy and breathe deep and let out a sigh that smells of oaten porridge and pewter and the inside of my own mouth.

I go to the rug. I circle twice, which is old habit and older. The bells do not ring. The candles burn at the crack and are very small. The seam of darkness is smaller now, the mortar fallen like snow caught at the edges. The golden eye is almost only paint. He stands there and his outline is stone and night and something between.

I lie down. My elbows ache; my hips whisper. My paws fold under me the way they always have, the way they did when I was pulled from a barrel full of straw and held to a man’s beard and given the name that means peace. My breath goes in. My breath goes out. There is the small sun on the floor that the window makes and I put my cheek in it because I always have.

Across the cloister stones, my paws have known every echo. Now the stones remember for me. The world goes on smelling of apples and bells and reed-sweet. A fox coughs far away. In the crack, the golden eye closes, not from cold but because nothing watching needs to watch any longer.

The abbey bell, satisfied, shivers once and is still.