Three Taps at Midnight

Past midnight, Echo, a fifteen-year-old Beagle, limped along Main Street, nose full of rain and hot metal. The small town slept, but he tasted panic in the air. Sirens were silent; the clock tower ticked. He followed the sharp thread of fear to the shuttered depot. The scent pooled at the cellar grate, young and desperate. His heart kicked like a pup’s. He pawed, whined, listened. A muffled tap replied, three beats. Then the floor trembled, and a hiss rose from below, harsh as a snake. Echo pushed his muzzle into the gap, ready to bark, when something grabbed him.

Little fingers clawed into the wet frill of his neck. They were cold and fast, talons of a small bird catching a branch. Echo jerked back, teeth flashing, not to bite, just to get room to breathe. The grate scraped his nose. Through the slot a slice of face swam up at him, pale and streaked with grit, one eye wide and glassy. The hiss was louder down there, a steady snake, and under it a thin wet laugh—water touching something it should not touch.

A strip of cloth pushed through the gap. It smelled of apples and school glue and panic. Echo took it in his teeth on instinct. It went taut. He planted his paws and leaned. The cloth dug into his gums. The grate complained, a long sore groan, then held.

He let go and licked the small fingers that still clung to him. Another tap came from below, three beats. He knew three. Three had been the code in summers when the boy he’d slept beside—the boy with freckled knees and a conductor cap he never earned—hid behind woodpiles and under porches. Three taps meant I’m here. Three meant Don’t leave.

He pressed his weight against the grate, found the weak corner, and lifted. His hips shook. The old ache crawled up his spine. It rose a hair. It slammed shut. The hiss beat like cicadas.

No sirens. No footsteps. The town was blank as a held breath.

Echo whined once, high and hard, then turned and ran.

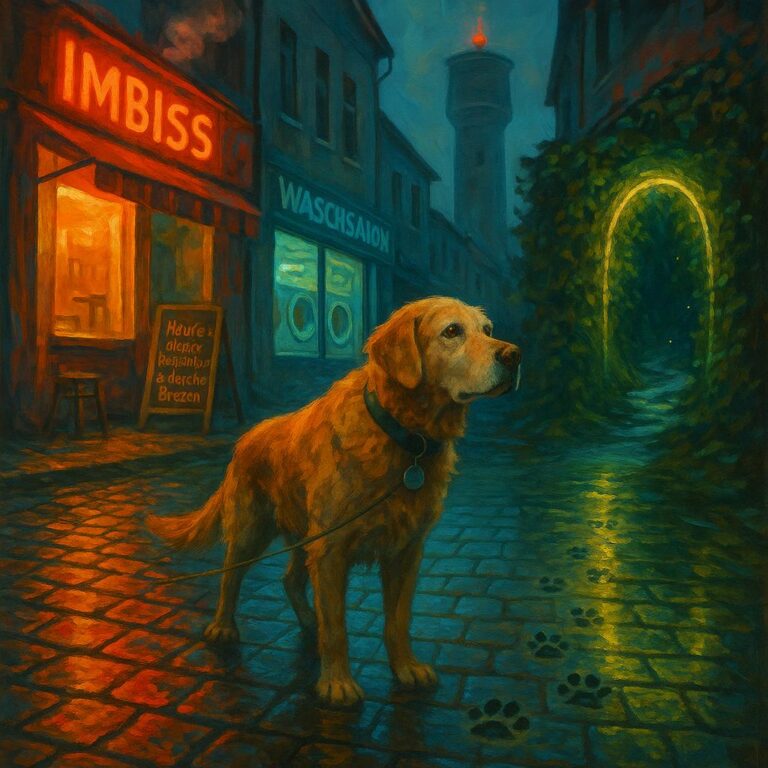

The diner’s neon S hummed a blue sorrow at the far end of the street. He took the center of the empty road, nails clicking like little clocks. Rain stitched itself in rows on his back. He veered into the light and threw his shoulder into the glass. The door bumped, did not budge. He pawed, he barked, he lifted his head and sent his cracked old howl up the block.

Alma looked up from the grill like a soldier waking. Wide arms, a towel over one shoulder, hair in a scarf. “Echo?” Her mouth made his name like she’d been waiting on it. “Hush now, you’ll bring the whole—what is it?” He spun, sprinted, looked back, sprinted again. He’d done this dance for years: This way. Now. Faster.

She grabbed the flashlight and a tire iron from behind the counter and followed him out into the rain, apron flapping. He took her down the alley that smelled like onions and old beer and cats, past the stacked crates, to the depot’s side. The metal grate gleamed dull; something white slipped between the bars, a bit of knuckle or tooth.

“Jesus,” she breathed. She dropped to her knees. “Hey baby. Hey. Can you hear me?” The three taps answered, brave as a bird.

Alma struck the grate with the iron. The clang shuddered back at them. “Rust-welded,” she said to herself. “Of course it is.” She flicked the flashlight beam through. The light came back in smoky ribbons. “Gas,” she said, then louder, “No more matches in the world right now, you hear? We’re getting you out.” She pulled her phone with slick fingers and stabbed at it, shouted something into it, and then she looked at Echo like his collar held all the answers. “Help me wedge it.”

He nosed the tire iron under the lowest lip where he’d felt a give. Alma planted her boots and pried. The grate moved, then sang and stopped. Echo threw his shoulder into the cold bars. Pain lit his thigh like summer lightning. He kept pushing. His paws slipped. He hooked one hind foot into the seam where concrete met brick and drove. The iron bit. The grate rose one inch. Two. “Hold it,” Alma grunted, and shoved a crate under the corner.

Echo slid himself into the open space, ribs scraping iron. He felt the boy’s breath on his cheek, sour with fear and the sweet of old gum. A face now, close enough to count lashes. “Hi,” Alma said, voice softened to Sunday. “Hi, sweetheart. Take my hand. One shoulder at a time.” The hiss popped, a change of note. Alma’s eyes went wide. “Now.”

The boy’s fingers shot up, slick, tiny. Alma caught his wrist first try and pulled. He stuck at the shoulders, panicked, scrabbled, slid back, screamed without sound. Echo did what his bones told him was right and bit the sleeve, gentle and relentless, to give the pull somewhere to go. He pulled with all the stupid old strength left in him.

The boy came like a stubborn root torn from clay. His shoes left wet tracks on Echo’s back. Alma swore and heaved them both up and out and away across the alley to the puddled grass. The hiss rose to a tea kettle shriek. The ground ducked once under them. Alma threw herself over the boy and hooked another hand into Echo’s collar and jerked. The depot coughed. A breath of heat pushed past. A window shattered somewhere, tinkling like ice.

Silence fell hard, broken by the long far complaint of the clock. Echo stood on spaghetti legs and shook. The world in his nose rearranged itself: plaster dust, wet oak, fried sugar from the diner clinging to Alma’s apron, the bright penny tang of the boy’s scraped palm pressed to his face.

“Ma?” the boy said, because now breath came back and with it the shape of that sound. Alma shushed him, checking his limbs, the little ribs that rose like paint-stir sticks. She was talking, to him or into the phone again, Echo wasn’t sure. Lights came in pairs at the end of Main—headlights, halogen, red coughs of emergency. The sirens, at last, woke and remembered the town.

“Back here!” Alma yelled, a bullhorn in an apron. “Basement! Gas! We need—” A medic in a yellow coat vaulted the curb, another behind him carrying a green case. Hands moved like fish. They tied a mask to the boy’s face and said things only to each other. The boy’s eyes stayed on Echo.

“Echo?” A woman’s voice cracked like an old board. She was tall in a coat too thin for the rain, hair loose and all the wrong angles. Her shoes splashed. She dropped to her knees without seeing where and gathered the boy into herself with a sigh that vibrated Echo’s ears. “Noah. Noah.” She kissed and scolded and counted fingers and kissed.

Noah lifted a hand off the blanket they’d wrapped around him and held it out to Echo. There was grease in the half moons of his nails. One stripe on his wrist where the grate had kissed him was white with shock. “I knocked,” he said into the mask, voice muffled and stubborn with tears he refused. “I knocked three like you told me, Mama. You said three meant you’re supposed to come.”

The woman laughed in the laugh that is a sob. “Your grandfather said that,” she said. Her palm went to Echo’s skull, heavy and certain. “He taught his dog to listen. He said this town knew how to answer a knock.” Her hand slid down Echo’s neck to his tag, the brass one shaped like a whistle. Her fingers stayed there a breath longer than a pet. “You old wonder,” she said to him, as if she’d just recognized him in a crowd.

He leaned into the weight of her hand. He liked the way humans used touch like punctuation, full stops and commas and sometimes parentheses. He liked that this one had remembered him when he wasn’t at his best or fastest, when his coat held more white than not.

They loaded Noah into the ambulance. He would be fine, someone said, who knew in their bones how to tell that truth. The volunteers dragged a heavy fan to the depot door and set it roaring. Tape went up, bright and suggestive. The clock told the hour like it had always meant to.

Alma sat down on the curb and patted the space beside her. Echo folded himself with the soft groan of old hinges. She took his wet ear in her fingers and squeezed it lightly, a game they had where she thought it made his thoughts straighten. “Mighty,” she told him. “Still mighty.”

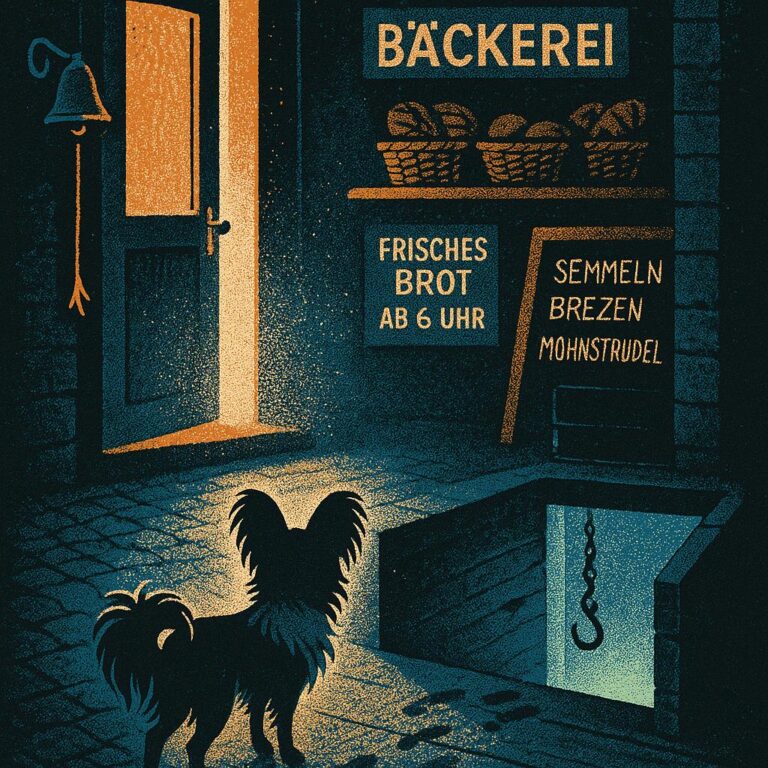

He put his chin on her knee. He let his lungs catch up with the night. In his nose, the panic thread that had wound him down Main Street untied and drifted. Other notes came back. Earthworms. Coffee. A bakery oven warming, two blocks over, their first shift early for once. He watched his own paws for a while, the pale half-moons of them, the broken nail on the left from some April ago.

Noah looked at him through the ambulance window, mask fogged with the small pump of his breath. He lifted his hand again—three soft taps on the glass—and smiled a crooked, brave smile. Echo’s tail did its slow old metronome.

The town reassembled itself around the hole in the ground. People leaned on each other and traded names for what had just happened, vesper murmurs with steam in them. Someone put a blanket over Alma’s shoulders. Someone else remembered to throw salt on the slick stone.

When they were done needing him, Echo stood. The rain had thinned to a ceiling of mist. He shook the depot grit from his coat and took his time walking back to where he lived now, which was exactly nowhere, which was exactly everywhere they let him in. He stopped at the diner door and looked up. Alma got there first. She opened it wide like a letter. “You earned a booth,” she told him.

He jumped onto the red vinyl with more care than he used to and tucked his legs under. Alma laid a towel over him and, as if the night hadn’t had enough heat, slid a plate with two strips of bacon on the table’s edge. “Doctor’s orders,” she said. He took them very seriously, in two deliberate bites.

By the time the clock tower remembered to chime half past, the ambulance was gone, the fan complained itself to quiet, and the neon S blinked in apology. Echo watched the window fog and clear, fog and clear. He remembered the boy with freckled knees tapping three under the porch, and the way he had always found him. He remembered the hiss and the crush of iron, and the little hand that had held onto his name.

He let sleep come the way it came to old dogs, sideways, with one ear still turned to the room. The diner smelled warm and human and safe. Rain stitched itself flat. Somewhere a woman said thank you to the night itself. Echo breathed and the sound of it filled his chest. The town curled around him like a pack, and the last of the panic left through the back door.

Morning would lift and scatter everything. Mail would run. The clock would keep a stubborn truth. He had done what he was for. He closed his eyes.