The Wrong Air

Even at fourteen, I still circle the feed store like a sheepdog on parade. I am Fergus, a Finnish Lapphund, born to guide, now the old nose of our small town. I patrol Main Street, greeting boots and bicycles, my girl Tessa laughing behind me. Today the air tastes wrong, sharp and hot, and the pigeons scatter from the courthouse roof. I follow the scent past the bakery, past Mr. Cole’s porch, toward the empty rail yard. Tessa calls my name. I bark once, twice, then see the open boxcar, dark as a cave, and something inside moves toward us.

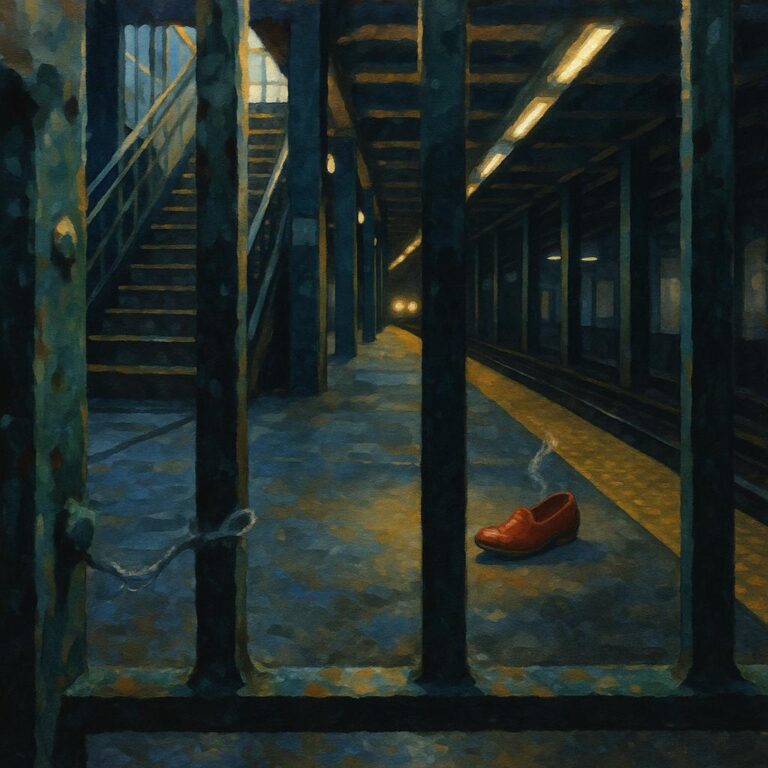

I plant myself between Tessa and the dark. The boxcar breathes heat, old sun and rust, and the air in there tastes like penny and fear. The thing moves again, low to the floor, scraping. Not a man. Too light. Then a sound comes, thin as twine: a whine.

Milk. I know it as soon as my nose finds the stream of it—sour-sweet and urgent. Milk and dog and iron nails.

“Fergus,” Tessa says, softer now. Her hand hovers above my back. I tip my ears and slide one paw forward, then another, pushing my chest to the ground the way elders do to pups. I blink long and slow. My tail draws a slow half-moon. I say without words: It’s alright. Come.

Two eyes lift from the dark, reflecting the sky behind us. A head. Ribs like fence slats. Her belly hangs low, tight as a ripe melon, teats swollen and dust-marked. She takes one step, then stops, teeth showing in a tired ripple. The boxcar floor is hot enough to make the pads sting. The air is the sharp I tasted before, the bite that says hurry.

“Tessa.” I don’t have her words, but I push sideways into her shins until she looks down. I look from her to the storefronts, to the feed store, to the water dish that always sits by the door, blue plastic faded to white at the rim. She understands quick. She always has. She runs, and her shoes patter away.

I hold my post at the door of the cave. The mother dog noses forward and back, indecisive circle, a trapped dance. I give another low whuff, friendly, just breath. She listens. Brave girl. She comes two steps and falters when the rail sings under us, heat ticking the metal. I put my paw on the lip of the boxcar and then off, show her the way out. My joints complain, but I keep them quiet.

Tessa returns with the blue bowl full, sloshing, and Mr. Cole’s old towel flung over her shoulder like a banner. Her dad’s voice floats faint from somewhere, the way a gull cries before you see it. People always find the place you circle.

We get the bowl just outside the boxcar, half in shade, half not. I step back and let my body be a bridge—her eyes go to mine, skip to the water, back to me. She chooses my eyes. Comes down in a slow, stiff spill, pads tapping the metal lip, then all four feet on gravel. When she reaches the bowl, she drinks like she’s fallen into a river, fast and brutal, then lifts her head to scan. No one reaches for her. She drinks again.

The sharp in the air strengthens. I lift my nose and the wind labels it for me: smoke, new, still small, the kind that runs along grass rather than curls like a snake. Down the track, past the weeds that grow as tall as a pony’s belly, a line of fire broken into coins steps along the dry stems. The pigeons had known. My spine hums. I circle hard, nose to Tessa’s knee, then point my muzzle at the bright, then back at the mama dog, then at the street.

“Fire,” Tessa says, voice split and thin. She’s already pulling out her phone. Her fingers are quick. “Main and the rail yard,” she says into it, and I think of our volunteer siren, the one that mashes sound like thunderstorms do.

We cannot wait to be saved. The mama dog sways where she stands. I nudge her shoulder and begin to walk, not away from her, but in front of her, slow, the way I do with lambs when the pen gate creaks and they think it’s a mouth. She follows because I give her nothing else to do. We cross the gravel, the hot patches, the cooler shadow of the boxcar wheel where the grease smells sweet. Tessa moves with us, sideways, the towel open like a leaf in her hands, ready to catch what falls.

We get to Mr. Cole’s porch as the first crackles leap up the weeds. He is there now, bare feet, garden hose pulled like a green snake, face red from his nap. He sprays a lazy arc that turns fierce when the wind brings the smoke to his mustache. Other people blink into existence—Mrs. Navarro with a bucket, the boy from the bakery with his apron on backward, the sheriff’s nephew with a shovel that shines like a mirror. They hit the fire with water and dirt and noise, and the fire, arrogant small thing, decides to go be a rumor instead of a disaster.

On the porch, the mama dog sinks onto the towel Mr. Cole throws down, then stands again, then sinks. The water runs out of her mouth in a pink thread. Tessa holds her hand near but not on, letting the dog choose. The belly tightens. The dog’s eyes find mine, not Tessa’s, mine, and I feel old and right, all the years of chivvying, all the times I’ve set poster boards on legs instead of letting them fall.

My girl whispers, “It’s happening.” Her voice turns very young and very sure at the same time. She thinks of school science and the rabbits her uncle kept and the time I got glass in my paw and she watched the vet pull it out. She thinks of holding on until help arrives. I think of warm things that are soft even when the world is hard.

I lie down just at the edge of the towel, my nose close to the mama dog’s flank where the milk smell is loudest. People move carefully and loudly around us in equal measure, the way they do when they are trying not to look like they are afraid. Tessa hums the thing she hums when storms dump nails on the roof. The mama dog rides a wave, and then another, and then the first pup arrives wet and silent, then complaining, pushed with quick, fierce licks into a slick of life.

We get three. One brown as toast, one black with a white toe, and one the color of wheat berries with a stripe down his nose like a spilled splash of milk. The fire is already a story on somebody’s phone by the time the wheat berry one finds his first meal, pawing at his mother’s belly with the impatience of the new. The siren finally winds down and the hose trickles to a stop, and I close my eyes, because I can, because the air goes back to tasting like our town—grain, oil, summer, sugar, the far-off river.

Days tilt and fold. The mama dog—she gets the name June because she arrived hot and needed shade—sleeps and eats what Tessa carries, and the pups grow like secrets kept well. On the mornings when my hips are generous, I loop the feed store again, patient as the moon, and June watches from the porch as if taking notes. People’s hands smell like flour and sawdust and the brand of dog biscuits that always live in Mr. Cole’s pocket. They stop to put those hands on me, old, and on June, tired and bright, and on the pups when they are big enough to wobble out and tangle themselves in shoelaces.

When the wheat berry pup opens his eyes, Tessa laughs because they are the exact color of the river after rain. She gives him a name that fits in the mouth easy—River—and he answers to it in the way of the young, which is to say he hears it everywhere and always.

I teach him without telling him I’m teaching. I show him how to read a bicycle by its chain-song, how to step aside for the wagon with the unpredictable wheel, how to lift his nose at the same places I lift mine: the bakery vent, the post office drop, the hole in the fence where the fox passed in winter. He stumbles and skids and attacks his own tail as if it insulted his mother. He wears himself out and sleeps with his chin on my foot, and the heat in his little jaw feels like a coal, not the kind that burns the field, the kind that makes tea.

Not all days are easy, even for heroes small and old. Some mornings I am more bones than bark. On those, I take my time. River bounces like a ball somebody forgot to catch. I circle tighter, inside the line he makes, and he learns the shape of the job by the shape of my shadow.

When he is almost too big to tuck under the porch rail, the pigeons scatter from the courthouse roof for no reason at all, just practicing. He startles, but he does not chase. Instead he looks at me. I sit. I let him see it: the quiet. He matches me, one beat later, and his breath slows. The town exhales with us.

That night, Tessa and I sit on Mr. Cole’s porch. June is asleep with her nose pressed to her paws, and River has found a place at my back, warm and certain. The air is clean. The tracks are only tracks. Someone laughs out front of the bakery; someone else locks the hardware store and goes home. My girl puts her hand on my ruff and finds the soft place between ear and collar that she’s known since I was more river than stone.

I was born to move things where they belong. Today I moved fear into water, and a mother into shade, and new life into the heart of our town. Tomorrow, River will circle wider, and I will circle tighter. The work will get done because noses know, and feet remember. I shut my eyes and let the sound of Tessa’s humming fold over us like the towel on that hot day, and for a long while, everything holds.