The Well’s Whisper

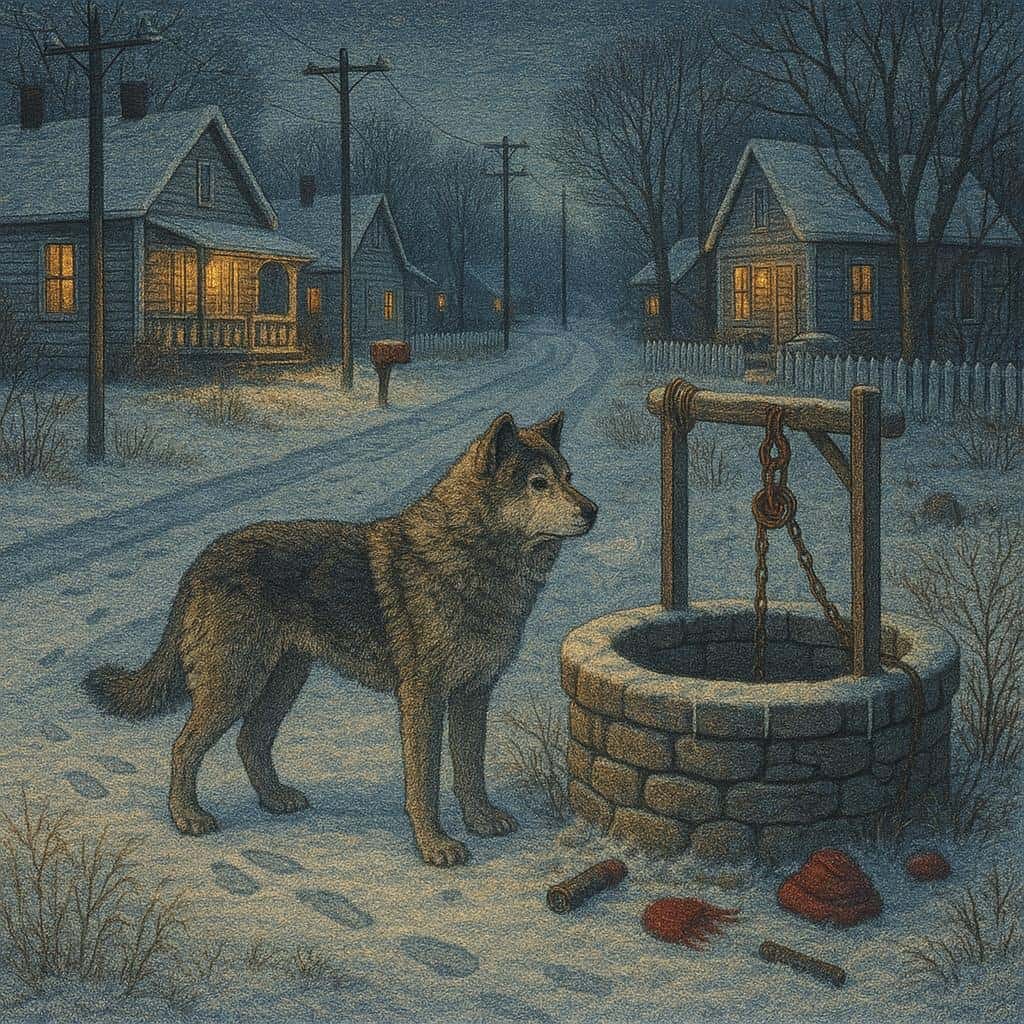

When winter dusk settled over our village lanes, Aiko the Akita, fifteen winters old, listened to the world hold its breath. The old dog moved carefully, but inside he said, I am not done. Every door knew his pawprints. Every mind worried about the boy lost near the chalk road. I knew the ache in Aiko’s hips and the bright wire of his will, and I knew the sour metallic scent drawing him to the dry well. He peered into it, ears forward, as a whisper rose from below and a second scent climbed up behind him.

He didn’t bark. He lowered his chest until his claws found stone and he leaned out, neck long, breath combing the cold. I heard it too then, the whisper that had been a rumor in the lanes all afternoon stretched thin and real: help.

“Aiko,” I said, too loud, and he flicked an ear at me without taking his eyes from the dark.

I smelled it then. Not the boy. The other. Rank and root-sour, an old boar’s musk braided with turned soil and rot. It slid up from the hedgerow behind us, a shadow heavier than the others. Snow had not yet started but it was coming; the air had that iron taste. My hands found the braided rope at my shoulder. We had brought it because of Aiko, because even as a puppy he had a way of standing in the middle of a thing until you gave in and did the right work.

The well yawned in front of him, stones slick with a skin of nighttime damp. The whisper fluttered like a moth’s wing. “Aiko?” The boy’s voice, thinned with cold and thirst, climbed out of the throat of the earth. Aiko’s ears came forward so suddenly his whole skull seemed to sharpen. He grunted low, a sound none of us ever admitted we understood. Down. Wait. Not alone.

Behind us, a twig cracked. Aiko turned his head just enough to see, not enough to give up his vantage. The boar eased out from the brush, shoulders like boulders under a shag of dark bristles. One small eye fixed on Aiko. The other on me. It must have been nosing the lanes, not afraid, pushed by hunger toward our gardens, toward our children. The night pressed close around its breath.

“Go,” I said to Aiko, even though I was the one who had to move. He made his choice faster. He slid to one side, placing his body across the lip of the well, an old soldier guarding a gate. His tail hung still as rope. His feet set. He showed the boar one shoulder and not the other, nothing wasted, every hair saying, you come past me, you go over.

I tossed the coil and it struck the stones with a soft clack and fell into the dark. I had the presence of mind to hook the other end under the old iron cleat in the wall, the same cleat that had held the bucket before the spring gave up and the village called the well dry. My fingers were already raw from the cold and from the day’s worrying. Now they bled a little, quick bright pain that made me breathe easier.

“Hold it,” I called down, forcing steady into my voice. The rope jerked and bit, and somewhere in that black throat the boy sobbed and then swallowed it. “I’ve got you. Hands and knees. Hook your foot. Take your time.”

The boar’s hooves picked out stones. It blew a wet grunt through its tusks, glistening, a knife’s edge on one side chipped to a wicked hook. Aiko’s lips peeled back, not a snarl. A promise.

He had been a beautiful dog once, all bright alarm and white blaze, but even grayed and bowed he was a line you could not cross without it meaning something. He had broken fights and herded toddlers and slept under thunderstorms. He had gone to the river and watched the salmon ladder when his hips were still sure and brought back a drowned glove as if it were a bird. And now he slid one forefoot forward and then the other, weight low, head lower, until the boar decided we mattered more than the hedgerow and tossed its head and came.

The sound of it was wrong. Soft. No trumpet, no raised dust. Just speed and will and the dull piano of hooves. Aiko let it close the distance and then he moved in the space between two heartbeats, something I had seen him do when he was three and something he had never forgotten. He shifted, he yielded, he was suddenly where the boar’s shoulder would be if the world had slowed down, and he drove the hard hinge of his jaw at the right place and held. The boar screamed high and surprised and Aiko’s teeth slid on greasy bristle and landed on skin. Then the tusk found him. It raked his side and the old dog’s body shuddered but he did not let go.

Below me, the rope jerked twice, then the weight on it grew. I planted my feet, heel to stone, thighs burning. Frost broke under my boot and squeaked like mice. “One hand above the other,” I told the dark, because it’s what you always say when you’re pulling anyone out of anywhere. The boy’s weight was wrong. It swung. His shoe scraped, found a crack, slipped. He choked and coughed and said, “Aiko,” like he was telling me a secret password. I pulled. The rope burned hotter. The boar hammered the stones. Aiko shook his head and his collar jingled once, a bright domestic sound in the middle of old, wild business.

The boar tore free and came again. It wanted the easy win, the hole, the small thing in the earth. Aiko put his whole tired self in front of that want and the world had to go through him to get to it. He drove sideways this time, gave the boar a flank to look at and took a leg when it was offered. The tusk ripped flesh and heat poured into the winter. I tasted it, iron and animal. He did not cry out.

Hands appeared at my shoulders. The baker’s wife, the one with thick wrists from kneading, barefoot in hurry, hair unpinned. Old Fumi with his lantern, his breath whistling. A rope over rope. We three leaned back as if the night were a plow we’d agreed to pull. The boy’s head came up, then his elbows, then his wet face paled with chalk dust. I got my hands under his armpits and the baker’s wife swore and Fumi said a prayer so small it was only a breath. We dragged the boy over the lip and on top of our knees and wept into his hair.

Aiko fell silent. Not down. Silent. He was standing, but only because his belief in standing was stronger than his body. The boar turned, saw the child, saw the narrowness of its window, and decided badly. It came a third time, this time with anger. Aiko moved straight into it, not to dodge but to decide the place where the two of them would meet. If he let it get past him, even a hand’s width, it would be a story we told apologizing to each other for the rest of our lives. He hit it at the shoulder and his teeth found the thick meat of the neck and held. The tusk came up hard and then lower and he took it. He took it and did not fold. He wrote a line on the boar’s hide with his mouth and the boar wrote a line on his belly and the winter sky wrote its own thin line above us, a new cloud forming where the world lets go of its heat.

Then the boar broke. Its bravado leaked out, its body remembered the old fear of anything that stands and looks at you without blinking. It huffed, it took a step back, it threw its head as if to shake off a story, and it went sideways into the hedgerow and was swallowed.

Aiko took one step after it and then stopped. He turned his head to me and then to the boy. He put his ears halfway up, the polite version. The boy crawled across the stone and reached, fingers shaking, and laid his hand on the wet fur at Aiko’s shoulder. “Good boy,” he said, like he was saying thank you to a person. He whispered it until his teeth stopped knocking.

We wrapped the boy in the baker’s apron and Fumi’s coat. We bound Aiko’s belly with my scarf and a second rope Fumi had brought in case the first one was not enough. There is a kind of laughter that comes when you are not dead yet and it sounds like someone else. It followed us as we went slow along the chalk road toward the village lights. Aiko walked with his nose an inch from the ground as if reading a note the earth had left him, as if the note mattered and for once it was for him and not about work. He did not stumble. He did not cry. He allowed the boy’s hand to rest on his back as a man would allow a stranger to lean on him when the bus lurches.

At his gate, which knew his paws, he paused, and we all paused with him. The boy, whose name was Kenta and whose mother’s hair I would remember being stuck to her cheeks with tears, would not let go of Aiko. He pressed his cheek to Aiko’s neck and Aiko closed his eyes and breathed that one deep breath he always saved for someone else’s trembling.

Inside, the house smelled of rice and tea and old cedar. We made a place. We made it with blankets and hot water and those words you carry down the years that are neither prayer nor command but are the rope you throw and pull hand over hand. The boy was carried home. There was a new noise in the lane, the relief of a village darting from porch to porch with other people’s business. Snow began softly, just enough to make the footprints crisp, to lay white on white over the chalk road like an erasure.

I sat with Aiko. I put my hand on his paw and his toes flexed once around my fingers, a puppy’s reflex waking under snow. His breathing sawed gently. The blood slowed. He looked at me and then past me in the way dogs do, as if trying to recall an old smell from when the world was younger. We had promised him, years ago, that when it was time, we would not ask him for one more duty, one more watch. We had broken it. We had asked. He had answered. The answer had teeth in it and a soft mouth.

The door opened. Kenta came in in his mother’s arms, a quilt around him, his eyes bigger than the rest of his face. “He’s here,” the mother said because she knew what a child needs for the rest of his life is a sentence that ends right. Kenta slid down and walked in bare feet across our floor. He knelt again with Aiko and held the old head. “Please,” he said to me with his whole body, as if I could turn the wheel back.

Aiko’s tail moved once against the blanket, a small thump like a listener agreeing with a story. He pushed his head into Kenta’s hands and licked the salt from the boy’s wrist. He looked at me again and the wire in him, that bright wire I had always felt thrumming, went slack without breaking. He placed his muzzle on the floorboards like a book being put down carefully.

Outside, the temple bell marked the hour and the first drift of snow gave up its grip and fell from the plum tree with a muffled sigh. The world exhaled. The room stood very still to make a space big enough for gratitude. Aiko took that space. He filled it. He let his breath ease out and did not pick it up again.

In the morning, the chalk road was a clean stripe, our prints, and his, and the boy’s small ones doubled where he had come back and forth, a shorthand for love in the powder. I carried Aiko wrapped in the old quilt to the hill where he had watched the salmon, where he had once turned and looked at me as if to check we were seeing the same night. We gave him to the ground there. Kenta set a stone by the cedar root. He whispered something to the place between sky and branch. It was not a prayer. It was the promise children make to the first brave thing they ever witness and believe they might, someday, be.

The village thawed. The chalk road showed itself again. Every door still knew his pawprints, only now we kept them in our mouths, telling. In the evenings, when winter dusk settled and the fields inhaled, you could almost hear it: Aiko listening back, not done, exactly, but known.