The Scent of a Leash

Perched on a tenement stoop, Lumen the Papillon, fifteen and bright eyed, watched the city measure time in headlights. In window 6B a nurse counted breaths of a plant, in the gutter a coin dreamed of hands. Lumen had learned that old bones listen better than they run. Tonight a wind rounded the block and carried a scent that should not exist anymore. It was coffee and wool and the vanished wrist that once held his leash. He followed into the lobby, past mailboxes, to a blue door he knew. From inside, someone whispered his name, and the lock turned.

The blue door opened a hand’s width, and the apartment breathed out a year it had been keeping. Lumen stood in the seam of hall light and inside dark, his nose lifting to the old map of smells that unrolled—lemon oil, radiator iron, rain folded into wool. The voice was near, softer than he remembered and more certain. Lumen, it said again, like a small door opening and staying open.

He went in. The hinges sighed the way winter stairs do. No shoes had walked the thin runner in a long while, yet the carpet still remembered the places feet paused. On the wall his own collar hung from the brass hook, its leather having gone soft with his years. He touched it with his muzzle and the tag chimed once, a coin on a table.

The hand he knew came into the light. Not a face, not yet, just the wrist and the sweater sleeve and the smells that once bracketed morning. The hand hovered to let him decide, and he pressed his head into its palm. There was a star of warmth in the exact place where it had always been, right there between thumb and first finger, and the star traveled. It went to the old ache in his hip, it traced the white blaze on his chest, it reached the tender soft between his ears where thoughts unknotted.

Nothing clicked on the collar. There was no leash and then there was one, the weight of a thread you only feel when it slackens. The room leaned wider, the coat hooks becoming streetlamps and the rug’s woven field becoming sidewalk, and the hall let out into the outside that used to be theirs.

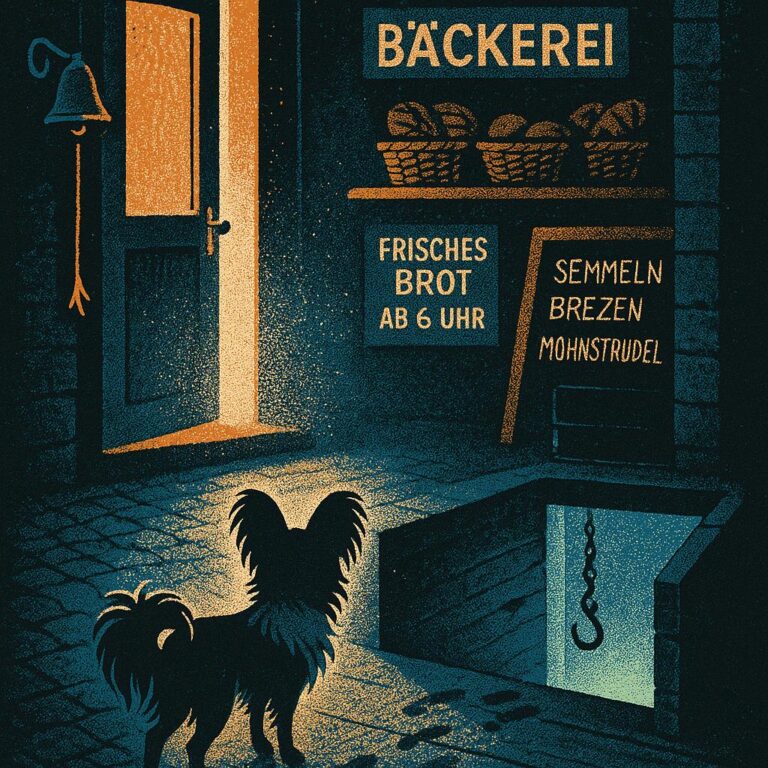

They walked the city Lumen kept in his body. He knew the cadence, even now. The stoop with its iron railing curled like a sleeping cat. The bakery that lived in the hot morning exhaust, though the sign was gone and the window was a phone store now. Steam rose anyway, because some smells are untenantable; they outlast their names. Pigeons lifted and arranged themselves on the wire like notes. A bus sighed at the corner and a woman laughed three floors up, and in window 6B the nurse paused her counting to look at the night she had not left in weeks. The plant breathed on its own.

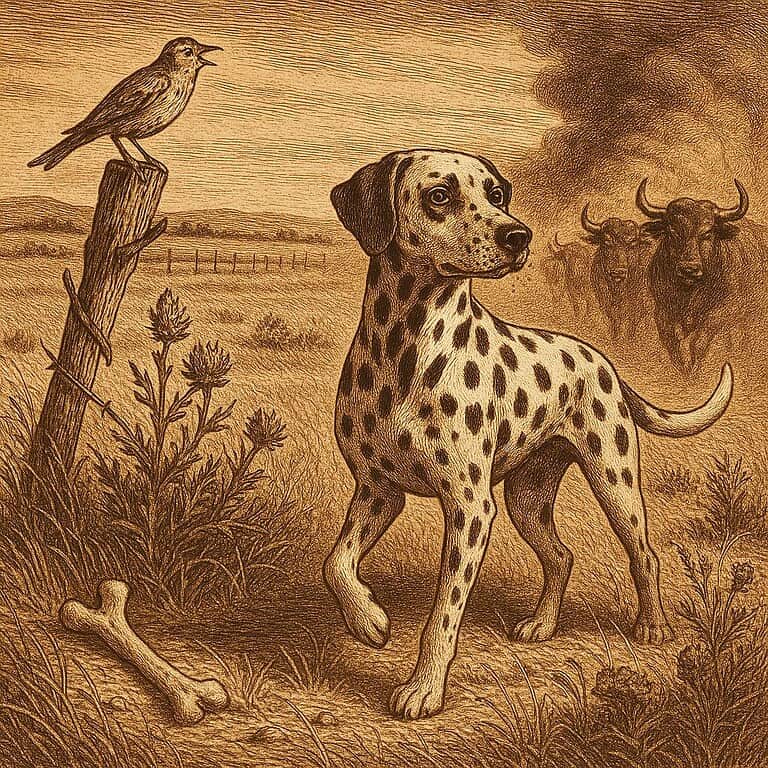

They did not hurry. Old bones listen better than they run. Lumen listened to the gutters narrate, to the newsprint scudding like fish, to the wind that had circled the block earlier and apparently had never stopped, just slowed to walk with him. He nosed a scrap that remembered a park, and for a moment his paws were in grass again, and the park was the size of the sky, and the sky was full of dogs he used to be.

At the corner where a coffee cart had once lived, a cup ring waited on a forgotten crate, a dark moon that never dried. The hand set a coin on it without thinking, the way old habits set themselves back on hooks. Somewhere in the gutter a different coin felt its dream conclude and went quiet. Lumen’s tag answered with a small clink from his chest, as if to say, I have my own circle.

They passed the bodega with the cat that played checker pieces off the board, though the board was a cigarette display now and the cat was a rumor. They passed the playground where he had learned to wait while a mittened child untied his ears by mistake and then tied them back with apologies. The hand kept time with his footfall. In headlights, in breath. The city did its counting; Lumen did another kind, tallying touch and voice and the weight of being seen.

The walk ran them back to the blue door because all good walks do. Inside, the lamp was a low moon. A bowl by the door held keys with their clever weight, and a single copper rested among them with a look of having always belonged. The kettle remembered the sound it should make and made it. Steam outlined the air, and the hand moved in it as though drawing a leash out of a fog and looping it around the years.

Lumen turned in a slow circle at the old rug and lay down. The rug held his shape as if it had been practicing without him. He put his chin across the arch of a shoe waiting there, the shoe that fit the foot he loved. The wrist came close. There was a steady counting in it. He matched it, his chest a small bellows. The city went on with its own metronomes—traffic lights, elevator elevators, the click of a neighbor’s knitting, the plant’s delicate lungs. The nurse in 6B stopped counting when there was nothing left to worry over and began to hum.

The hand kneaded the loose skin at Lumen’s neck. Good dog, the voice said, and the words were the same ones from the first snow, the flooded spring, the bathtub with its sharp-sided sea. He tasted the words. They tasted like peanut butter spooned out and shared while papers rustled and the world forgot its seriousness. He closed his eyes into the hand, and behind them the city arranged itself into the simple places—lap, bowl, ball. He was each age at once, ribs narrow and ribs wide, paws too big and paws just right. Between heartbeats there were entire summers he’d misplaced and now found, sticks retrieved from the farther throw, puddles chosen on purpose.

He listened one more time, because listening had become the good part: to the voice saying his name as if it were a door he could step through without being asked to hurry, to the radiator counting like a cricket in a cupboard, to the sweater fibers telling a story of rain followed home. He lifted his head, then set it back where it fit best. The leash between them loosened by an inch, not because he pulled but because everything did.

When he went, it was the way lights decide to rest when morning shows them the job is done. The street kept measuring time in headlights. Upstairs the plant went on breathing like a small, green city. The coin in the bowl stopped dreaming and simply was a coin. The wind rounded the block, less frantic now, and carried away the last of the night’s extra. The blue door stayed ajar until it had nothing else to hold. And the hand, which had never really been gone, kept its place, warm and sure, in the space his name had opened.