The Last Leap

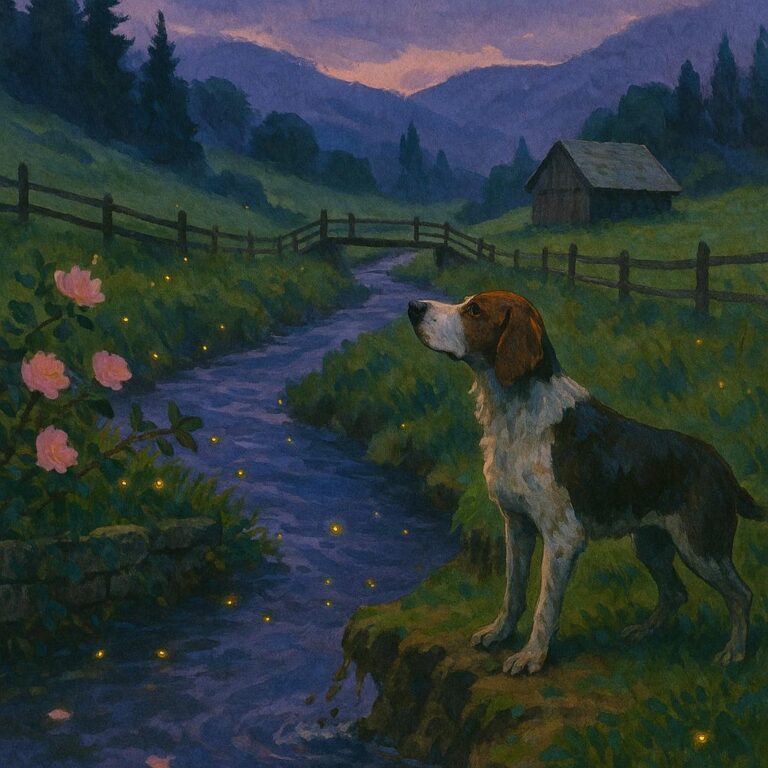

Maybe retirement meant more naps, but Kipper, a fourteen-year-old Border Collie, had other plans. The lake smelled like wet pancakes and mystery. His hips ached, yet his tail kept editing the air. He spied a bobbing neon tennis ball two piers over, clearly abandoned and clearly his destiny. He paced the wobbly dock, calculating like a professor of fetch. One careful leap, then a heroic paddle, then applause and snacks, he thought. A frog belched. The ball drifted farther, tugged by a sly ripple. Kipper crouched, sprang, and the water beneath him swelled with a sudden, silvery shadow.

He hit the water with a slap and a grunt, lake-cold climbing his ribs, his mouth filling with metal and cloud. The silvery shadow rolled under his chest—a fish, big as a backpack, turning one coin-bright eye up at him like, You sure about this, old-timer?

Kipper was absolutely sure. Or sure enough to pretend. He tucked his paws and kicked, kicked again, hips complaining in the voice of old porch hinges. The neon ball bobbed away, smug as a buoy. He put his professor brain on: angle, current, ripple, wind. Herding was herding, even if the sheep were made of tennis and tide. He veered, letting the sly ripple carry him past the ball, then arced back, a black-and-white canoe with a stubborn engine.

The carp—or whatever submarine ghost it was—ghosted alongside, a pale back breaking just once. Kipper ignored it with the professional courtesy of one elder to another. The frog belched again, a judge’s horn. The ball tried to escape under the skin of a small wave. Kipper swung his nose, touched it, lost it, found it again. He thought of the applause and snacks part of the plan and his tail, half submerged, wrote emphatic exclamation points in the lake.

He clamped the rubber in his teeth at last. It squeaked like a tiny argument. Lake water stung his throat. He turned for the dock, lungs counting beats, shoulders doing the heavy lifting now. Someone shouted his name—Ruth, high and tight; she didn’t want him to sink like a stone. A man with a tackle box paused on the next pier and gave a low whistle that had fishhooks in it. The sun poured itself on his back like warm syrup.

Halfway home, the current tried one more trick, pushing him toward a boat slip where the water deepened and shadowed. His jaw ached. The ball tugged at his gum like a stubborn duty. He pivoted again, a slow careful pasture turn he’d used on wayward lambs years ago. The ball came with him because it was his now, because he had decided it would be. That’s what destiny is, he thought: the thing you keep turning until it follows.

The dock’s ladder waited, two glittering ribs. He lifted a paw, scraped, lifted another, belly bumping each rung, heaving his wet weight up the way old dogs and older fishermen have always done. Then he was on wood, water running out of him and back into the lake with noisy relief. He shook, a storm all by himself, and everyone within radius received their baptism: Ruth, the tackle man, a girl with frog-green nail polish who giggled as her hair splotched her cheeks. The carp flicked its tail and stitched itself back into the mystery.

“Absolutely not,” Ruth said, bending, hands on his cheeks, wet forearms glowing. “Absolutely yes,” her eyes said, and then they turned into a sandwich. Not the whole thing—she had sense—but the crusts, ham-flavored, rich with the hands that made them. He crunched, the ball trapped under one paw like a hostage who had secretly applied for the job.

The dock stopped wobbling as his heart slowed. Somewhere a dragonfly zipped like a bright idea. The frog belched a last time, satisfied. Kipper lowered himself carefully, joints clicking like typewriters, and let the sun iron his fur. The ball was there. Ruth’s knee touched his shoulder. A breeze slipped its cool fingers through the reeds and brought him back the smell of breakfast and minnows, of rope and algae and the faint, heartbreaking sweetness of a pastry someone had smuggled into a tackle box.

“That was not the plan,” Ruth told his ear. He had always liked that she spoke to him like a colleague. He nosed the ball into her palm and watched her face gentling into a smile she saved for victories. She lobbed the trophy low and soft to the frog-nail girl, who caught it with both hands and a whoop. So the ball had been a mission, not a prize. Fine. That made sense. He had always liked missions better anyway.

The ache in his hips arrived as a suggestion, then a statement, then an essay with footnotes. He leaned into it and found, beneath the pain, a steady hum of satisfaction, the good dog’s choir. Maybe retirement was more naps. It could be naps and this. Naps and lake rescue. Naps and teaching the young what had to be done.

Ruth rubbed the white blaze between his eyes until the last of the swim shiver left him. “Hero,” someone said, quiet, not a big word tossed like a stick but a small one, set down near his paws. He didn’t know that word, not the way humans meant it. He knew the weight of a thing in his mouth and the feeling of returning that weight to the right hands, and the way the world lined up straight after you did.

Around them, the lake breathed and breathed. A heron lifted, slow as an old newspaper, from the far marsh. The silhouette of the carp, or its cousin, showed once more in a ring of ripples that found the dock and tapped it hello. Kipper closed his eyes and saw sheep-shaped waves, a meadow made of water, the young ones fast and foolish and the old ones clever, all of them following, eventually, the curve he made.

Sleep nosed him from the side. He let it. His ear still took attendance: creak of a cleat, shoe on wood, whisper of sandwich paper. Ruth’s hand, warm and always there, settled on his chest where the rhythm was steady again.

When he woke, the dock boards would be dry and the sun lower, a coin sliding to the pocket of the trees. There might be a second mission, or not. Either way, he’d be ready in the way that mattered—eye bright, brain ticking, tail making edits in the air. For now he let the day end without him for a little while, chin against the rescued ball, the lake’s cool breath in time with his own. Maybe retirement meant more naps. He could live with that. He had plans. And he had the good, simple job of keeping what floated from floating away.