The Hissing Tin

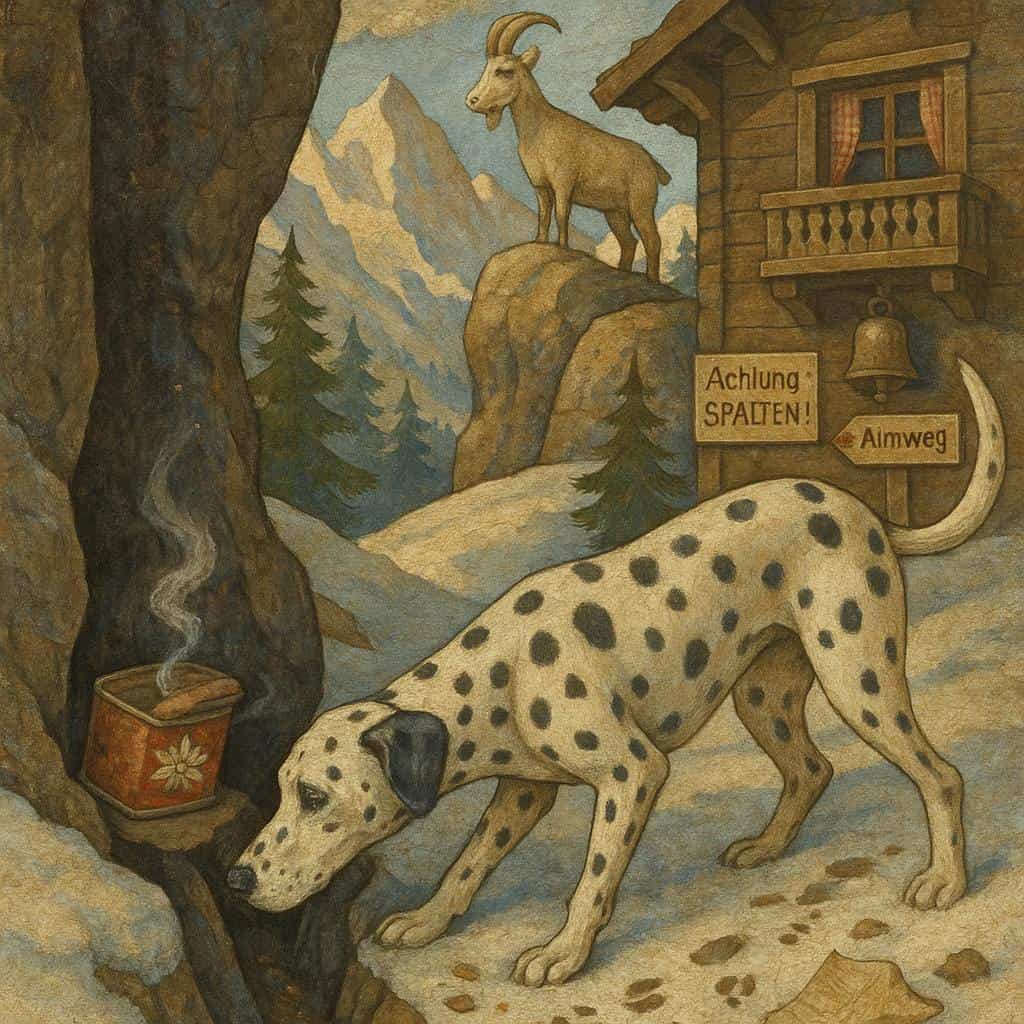

No one told Dashiell, a fourteen year old Dalmatian, that mountain retirement meant naps. He considered naps a negotiation. From the chalet porch, he surveyed peaks like giant chew toys, then waddled off on his daily patrol, joints squeaking but dignity intact. The air tasted of pine, snow, and last night’s sausage. Excellent clues. He followed the sausage trail past yodeling hikers and a smug goat, certain glory awaited. When his nose pointed to a narrow crevasse, he huffed, squeezed in, and found a tin that smelled like victory. The tin clicked open by itself, and something inside hissed.

Cold breath curled from the tin. It smelled like old metal, glacial, a basement that had waited a hundred years to exhale. Dashiell sneezed—one of those whole-body sneezes that rattle your ears and make your collar tags clack—and then the crevasse filled with a ribbon of milk-white vapor unspooling faster than he could sniff.

He knew fog. He knew when it arrived low and honest from the valley or crept sly from the lake, when it licked at your ankles and when it swallowed the world. This fog poured. It came with a faint crackle that made his whiskers buzz. It slid over rock, trailed over his paws, and then spilled down and out, spilling and spilling, as if the tin housed a very long breath that had finally remembered it was air.

He tried to nudge the lid closed with the flat of his paw. The tin spun, lid flapping like a small metal tongue. The hiss rose to a high, merry note. The fog slicked his nose and filled his mouth until all he tasted was wet chalk and a whispering of electricity.

Above the crevasse, the goat bleated once in a scandalized tone and stepped back as the white rolled over its hooves. Yodeling ceased mid-yo. Far-off, a bell stopped halfway between bong and ding, and the mountains around the chalet became paper cutouts folded away, then nothing at all.

He had lived long enough to know when a patrol had turned into a situation. Dashiell nosed the tin deeper, pinning it against ice with his shoulder blade, and shoved the lid with all his dignified weight. The lid kissed, missed, skittered. The hiss didn’t stop. Everywhere became the inside of an old cloud.

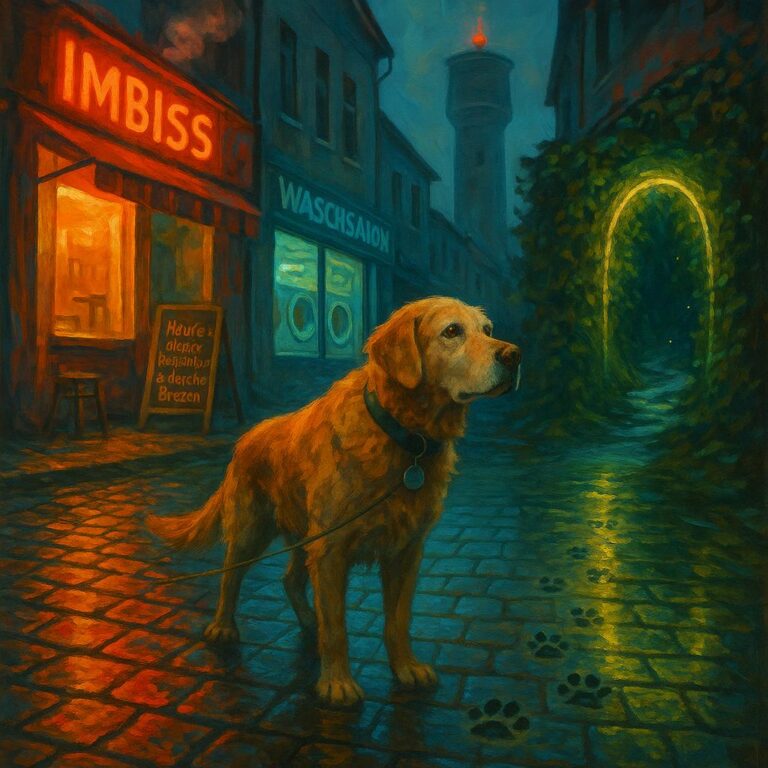

He did what his bones remembered before his head caught up: he barked the clear, rhythmic bark he had learned when snow fell wrong and voices disappeared. Two sharp, one long, then pause. He had not used it in seasons. It came out with a rasp along the edge, but it went, down the crevasse, up to where people would be turning in slow circles feeling like socks lost in a laundromat, and it came back to him in muffled echoes.

“Dashi?” That was a voice he knew, somewhere above and to the left. Marta who ran the chalet, who always smelled faintly of yeast and knit wool, who had hands that found the exact place behind his ear that made him limp with gratitude. There were other voices too—the thin one with the expensive backpack that always squeaked, the teens with the neon hats, all evaporated now into damp, blind sound. Pretty soon someone would step where the mountain kept its secrets.

He abandoned the tin long enough to wriggle out of the crevasse and into milk. His eyes watered. His spots vanished into the same white as the rest of him; only his black nose was certain. He moved, head low, ears forward, letting each exhale tell him what it bounced off. The goat ghosted alongside him, solid and silent and smelling of thornbush.

He found the expensive backpack by colliding with it. The man made a noise like a broken kettle. Dashiell leaned hard against his shin, stepping in a deliberate rhythm: forward, forward, wait. He had led enough people to know they followed better when you gave them something to do. He nudged again. The man’s hand found his collar and clamped. Good. One.

He looped in a wide circle, scooping up the neon hats by their uncertain chatter. One of them said, “Is that the Dalmatian from the porch?” and reached down, and Dashiell pressed his ribcage against her knees until her body oriented toward where the earth leveled out. They whispered to him—good boy, good boy—as if praising could thicken the air back into view. It helped. The rhythm of their feet behind him fell into his old internal metronome. His pads mapped the way by temperature and texture: scree rasping, grass slick, the faint gritty promise of the path’s gravel under the first layer of fog’s blankness.

As he shepherded, he kept the other part of his mind fixed on the crevasse. The tin kept hissing. The world’s edges were loosening. This fog felt unnatural, too eager, as if it had waited inside its metal belly for an invitation. He had given it one.

At the top of the first slope he left the neon hats at the goat’s shoulder. The goat planted its feet and lowered its head just enough to make a fence out of itself. It would hold them. Dashiell turned and vanished back into the blur.

His bark ricocheted and drew Marta like a thread pulling taut. She reached him with a laugh edged in panic, put both hands on his head, and said the thing he needed most: “Show me.” He did, walking backwards a few paces so she could keep her hands on his cheeks, then turning and pulling gently at the cuff of her trousers until her boot found the path and stayed.

He put them all—backpack, neon hats, Marta—on the groomed slope that always led home. He put them into the sound of the little bell that hung from the chalet’s eaves, now a small determined ding-ding-ding in the damp. Then he left them and went back, because the hiss had become an impatience in his bones.

He slid down again into the diagonal opening. The lid was half open, half closed, like a stubborn oyster. Fog roiled and curled out, eddying around his muzzle. He jammed a paw over the tin and pressed. He could feel the cold there in a way that went past the fur, straight through the pads. He pressed until the tips of his toes went numb. The hiss dropped in pitch. He held. He breathed. He recognized the metal taste of old machines and a memory surfaced of a poster tacked crookedly behind the chalet bar, from a time when someone thought it clever to sell „Canned Mountain Air“ to tourists, a cloud painted on a tin with a cork in it and letters in a jaunty font. No cork here. But a faint stamp on the warped lid revealed itself as he steamed it with his breath: a puff of cloud and a single word: FOG.

It had not been meant as a joke. Someone had put weather in a can and misplaced it. He’d found it.

“Are you doing something heroic down there?” Marta’s voice drifted over the crevasse, strained and light at once. The goat added a doubtful mmmm. She crouched, her hands patting just at the edge, useless and dear.

He dug his blunt nails into a seam and pried. The tin’s hinge screamed. He shifted his shoulder to change pressure, leaned his whole weight—the old barrel of him, the years of naps avoided and patrols logged—until the lid finally slapped shut. The hiss hiccuped. Then, with the faintest sucking pop, stopped.

Silence did not return at once so much as it remembered how. The fog around him trembled like something caught in deciding, then tugged, then began to gather. He felt it move past his whiskers, an invisible fur ruffling toward the tin as if the world were reversing a spill. He put his paws over the lid and kept them there even when he heard muffled laughter overhead—relief makes people giddy—and felt the warmth of Marta’s hands finally on his neck, her fingers sliding under his collar to take the weight should he decide to relax. He did not. He waited until the air thinned enough to show him the goat’s ridiculous rectangular pupils peering down. He waited until the shoulders of the peaks stepped back out of nowhere and the porch bell resumed its normal, sensible ding. Only then did he lift his paws and nudge the tin, cautiously, as if it were a hedgehog.

The lid held. The tin was dented now, the cloud stamp scuffed, the metal cool. He licked it once, because sometimes that helped, and tasted nothing at all.

They wrapped it in a scarf because that seemed polite, and Marta cradled it like a loaf fresh from the oven. “What are we going to do with this?” asked the man with the expensive backpack, who had discovered that being properly frightened makes you humble.

“Put it somewhere it can’t be sat on by a goat,” said Marta, whose wool had soaked to a darker gray, whose cheeks were pink. “And maybe tell people not to open things that hiss.”

Dashiell tolerated a fussing he would have ordinarily considered undignified. His head was rubbed, his ears kissed, his old ribs thumped with relief. Someone called him a hero, which he filed under Facts, Not Opinions. The neon hats took photographs of him in which, for a change, he was not just the handsome porch ornament but the warm spot in the fog, the small gravity that people fell toward.

Back at the chalet, the tin went in a cabinet behind the bar next to the jar of marigold candy only the grandparents liked and a signed photograph of a champion ski jumper who had once eaten four plates of rösti and fainted from joy. Marta wrote a label in thick, impatient marker: DO NOT OPEN. She underlined it twice. Then, because she knew her regulars, she added: EVEN IF YOU’RE CURIOUS.

The sun burned through what was left of the cloud, and the goat, its dignity restored, ate the face off a tourist map. Dashiell stood on the porch while his fur dried in strange scallops. The mountain had tucked its teeth away again. He allowed the breeze to turn the story over and over in his head until it lost its furious shine and became part of the day.

Someone brought him sausage without being asked. He accepted it with the solemnity such things deserved. He watched Marta retell the fog to newcomers with her hands, growing bigger every time she described the part where he jammed his shoulders into rock, which was fine with him. He caught the galvanic scent of storm from the tin even through the cabinet door, the tickle of it in the nose like thinking of thunder.

He completed his patrol from the porch with the lazy compass of his eyes, and found, to his surprise, no new business needed tending. The peaks sat up straight. The goat failed to fall. The hikers walked on their legs like people who knew where they were. He nosed at the boards where the afternoon sun pooled warm and golden as soup.

He arranged his old bones. He turned twice—performance matters—and lowered himself with each joint remembering it was a hinge. He faced the cabinet because he was not a fool. He placed his chin on his paws and lifted one ear so it could catch the sound of anything deciding to escape.

Retirement in the mountains, he decided, did include naps. Not as surrender but as strategy. You slept so you could do the next thing that happened. He closed his eyes and dreamed of canned weather and of moving through it, of noses making paths where there were none, of being the shape the world found when it needed a direction.

He slept, and the fog stayed in its tin. Outside, the peaks kept watch like patient, enormous dogs, and the air tasted, faintly and contentedly, of sausage.