The Cloister’s Breath

Night found Ivar, a fourteen year old Norrbottenspets, padding the silent cloister where incense braided with mist. He felt the stones breathe, old as his aching bones, and listened for the soft footfall of the monk who always slipped him crusts. Only the bell replied, a single trembling note that smelled like candlewax to his mind. He followed it toward the chapter house, tail held low, nose reading a script of dust and thyme. A mural fox blinked in moonlight, or so he thought, and then the reliquary lid shivered. Something inside scratched once, twice, then began to push.

He stood with his forepaws braced and nose lifted, drawing the news from the seam under the lid. Tin and old honey, iron and winter apples, a whisper of mouse, a deeper whisper of something that remembered blood. Between two breaths the scratching stopped. The bell in the tower took one small breath as if to speak and thought better of it.

Ivar nosed the hinge. The chill of the reliquary traveled up his whiskers and into his eyes. He pressed again until the lid answered with a patient sigh and slid aside the width of his paw. Air exhaled—cold as moonlight on birch bark—and ruffled the fur along his spine.

What rose was smaller than he expected and bigger than any rat. It had the shape joy has when it runs in snow: quick and low and sure. Dust seemed to knit itself to fur, gold leaf to guard hairs, a brush of tail knitting last of all. The mural fox on the wall missing a stroke of paint at the hindquarters blinked without eyes. The thing that climbed out shook once and showered the chapter house with motes that smelled like fennel and ash.

Ivar’s lips twitched back, but his old throat held the bark. He knew fox. He knew the taste at the back of the world that said fox, the high salt, the sly sap. In his pup winters he’d dammed his voice in the deep snow and sent it up the trunks to hold a red back in a spruce. Those days had run off with the melt. This creature wore those days like a remembered coat and looked at him with more than eyes.

It stepped delicate onto the stone as if the centuries were damp moss and touched its nose to his. The touch was a little burn. He smelled field edges, goat stink, eggs in hedges, the first peel of frost from a puddle. Under it all a sweetness that didn’t belong to meat or fruit—a sweetness of vow and candle smoke: the monastery’s breath woven into fox.

The fox turned and went, no shiver of claws on tile, no sound at all, only the line of scent it drew behind like a string. Ivar followed, because that is what you do when a story you know wakes up and asks.

They moved through the chapter house, past books that smelled like green walnuts and rain, under saints stiff as birches, through a door that had learned all the footsteps and had forgotten none. The cloister walk had a fur of moss. Ivar’s pads pressed it flat. His bones whispered. The fox’s tail was the moon’s scythe cutting the mist into thin bread.

He looked for the monk with crusts. The soft, butter-crumbed hand, the murmuring voice that patted his rib cage with a rhythm that made sleep come. He did not find him. Only his absence had a weight—like the bowl he licked clean each noon set upside down.

The bell shivered again. One note. It smelled less like candlewax now and more like wool warmed by a fire and then shaken. The fox tilted its head toward the sound and notched its ears at the garden door.

The iron latch was a mouth too high for Ivar. He sat back, lifted his muzzle, and gave a little chuff, a sound from before speech. The fox rose on its hind legs and put it together. Nose to latch. The tongue of iron lifted with a thrum he felt in his chest, as if the bell were in the bolt. The door opened, and the garden was a recipe he remembered: earth, thyme, frost, the lead tang of the old well, holly oil bruised under bird feet.

They crossed the flagstones. Ivar paused where the monk always stood and tossed him crusts. He breathed deep, searching the cracks for the Monk-smell—soap, ink, the salt of the sea captured in the wool of his robe and never fully rinsed. A smaller scent found him: a thread of grief, just fallen, fresh as cut pine. He didn’t know the word for it, but his body did. He shook his fur once, and the shake went deep as marrow. He tracked the fox’s line between the rose stubs and the cold fig.

At the far wall the ivy had fingers. The fox sprang until its shoulders were even with the coping stones, and then it stopped and looked back at him. It wanted the gate, not the scramble. It wanted to go out properly, through the mouth of things, not their broken tooth.

The gate into the meadow stuck every spring and every autumn swelled. Now it stood as if waiting. The latch wore a string of rust beads. This time Ivar leaned his weight and felt the hinges consider the matter. The fox flowed around his legs and pressed at his side, a small constant push, the way very young pups lean into their mother’s ribs. The gate gave, and meadow air poured in, long grass cut months before and still talking, field mice stitching little silver messages, frost writing the last of them over.

They went into the stubble field where the moon had come to ground. The low stones that broke up the row wore caps of lichen like old men’s hats. Somewhere a brook said yesterday’s things and did not tire of them. The fox went a pace ahead, then fell back, then matched Ivar’s, which had shrunk in the last months to this patient four-four of breath and step.

At the field’s margin a birch leaned crooked, white bark peeled back like pages. Under it a hollow held the dark like a hand. The fox went into the hollow and came out carrying nothing, then went in again. When it stepped out the third time it carried a smell.

It was not a thing he could see. It was a season, or a promise, or a word spoken on a winter morning when the breath knits it to the air. It was the beginning and end of someone’s story, and it hung from the fox’s teeth without weight.

He saw other traces now. A small polished bone set under a red ribbon. A scrap of hide, fur gone to dust and then to dream. He understood. The reliquary had been a box that kept an idea: a fox given up and made sacred. The idea had tired of its own corners. It wanted wind again.

The fox dropped the not-quite-thing at his feet and bowed its head. Ivar bent, and the smell stood up in him. For a heartbeat he was young and arrowing through pines, snow hurling itself out of his way, a red tail ahead, the sound of men laughing behind, the promise of a hand on his ruff and the warm men-room at the end of day. Then he was old again, and his breath had to climb to get out.

The fox picked it up and set off across the meadow, not toward the woods but into the low place where mist collects. Ivar followed until the ground went damp and the reeds told each other stories with their knees. The fox waded into the fog, which was not deep, and lay the not-quite-thing down as one lays down a sleeping pup. The mist took it without notice, and it went into every place at once.

They stood there together while the meadow took a new breath and let it out. The bell in the tower of stone gave one more small note. This time it smelled like warm milk and the inside of a den in spring.

Ivar’s legs shook as if new. He sat. Then he lay, the old way with his head between his paws, one ear cocked for news, as if an early thrush in the hedge might tell him something. The fox circled once and lay down against his ribs. Its fur was a story told in a language that lapped at him and did not demand answers.

He did not count his breaths. He did not think of the gate, or the monk, or the empty bowl. He listened to the ground. It spoke stone and root and the tiny crisping of frost making lace of the leaves. Somewhere a mouse corrected another mouse. The stars had set their mercies, and one fell and brushed his eyelids with its tail.

When he woke, he would go back to the cloister and find the monk or the monk would find him and feed him crusts and scratch the place on his chest where the old cough lived. Or he would not wake, and the fox would carry what remained of him where it was supposed to go. Either seemed right. He had carried; now he could be carried.

The fox lifted its head when he loosed a long breath that did not entirely return. It put its nose to the hollow behind his ear and smoothed the fur there with a gentle, useless lick—the way animals do in the face of weather they cannot command. The gate clicked in the distance as if a hand had touched it and then set it careful.

When morning came, the cloister would remember that the reliquary lid was a little off true and that a fleck of gold leaf had worked itself free and sailed like a moth. Someone would say the saint had sighed. The monk would stand at the garden door with a bowl and not call. The bell would not ring. The mural fox would have a thin pale place where the paint was rubbed, as if someone had stroked its flank to comfort it.

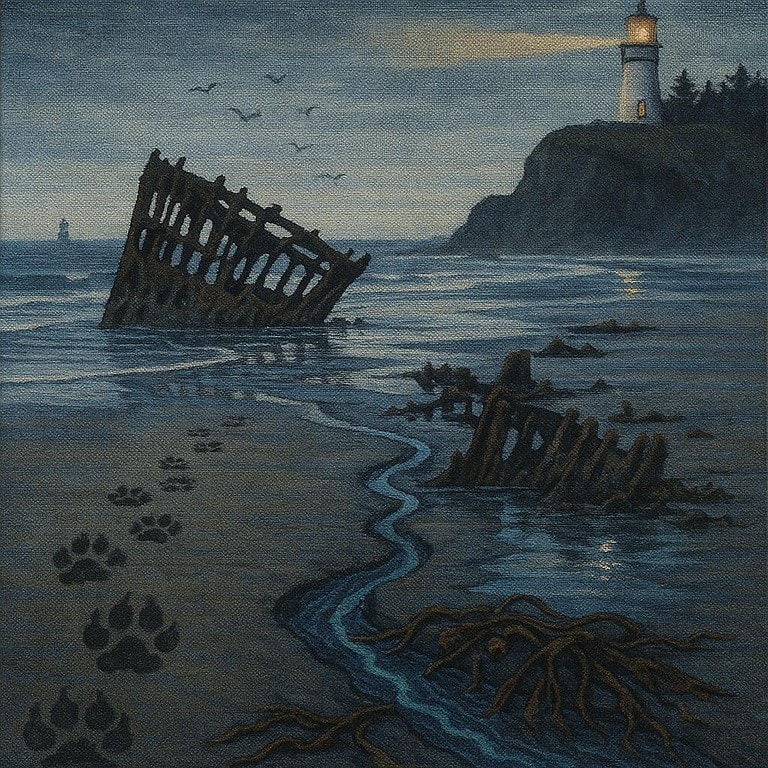

Out in the meadow, thyme invisible under frost would breathe. A white dog and a red fox would be a rumor the grass kept and did not waste on birds. A ribbon of old red would soften in a brook and ribbon the water more redly for a yard before it forgot it ever had color at all.

Ivar shifted once and found a last good angle for his bones. A luck, like a soft paw, pressed on his heart and kept it. The fox lay his head over Ivar’s paws as the first light came, and with it an easy, unremarkable end to the night.