Prairie Thunder

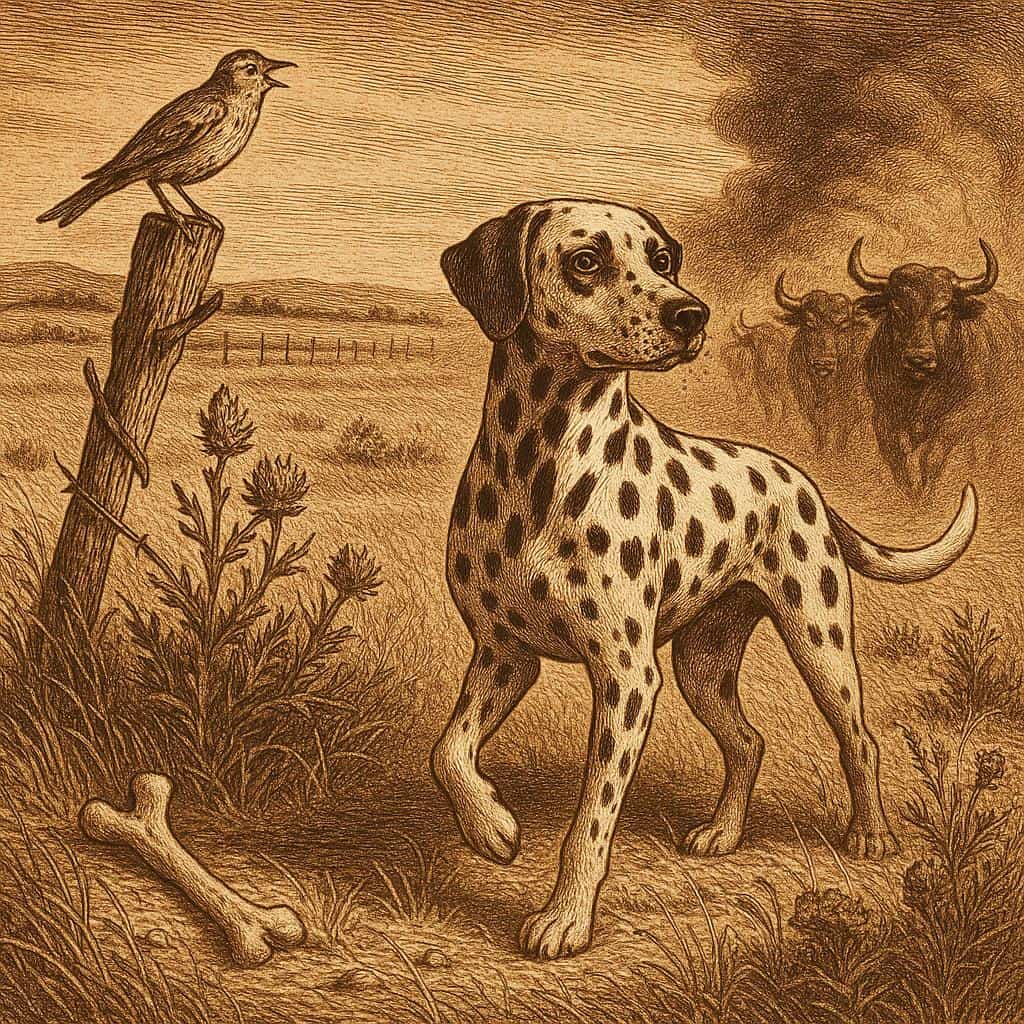

Fritter crumbs freckled Huckleberry’s muzzle as he surveyed the prairie like a retired sheriff. At fourteen, the Dalmatian believed the wind existed mainly to deliver snack smells. He padded past sage and sun bleached bones, thinking the horizon was just a long, flat nap. A meadowlark heckled him; he heckled back with a wheezy bark and a jaunty wag. Then the ground hummed. Dust lifted in a long brown ribbon. That is not a nap, he thought, ears pitching forward as a shadow rolled over him and something huge thundered straight at him.

The shadow resolved into a horned wave. Not storm, not cloud—backs and shoulders and beards and eyes, a shaggy river of buffalo pouring down the draw, the kind of prairie weather nobody can predict. The ground did not just hum; it spoke in ribcage language: move, old spot, move now.

Huckleberry’s ears had been good once. They still remembered hooves. He’d run under wagons in a town where iron shoes rang on cobbles and a bell lived on a red truck; he’d known how to stay in the sliver of safe, the seam between thunder. Hooves meant lanes. That old knowledge rolled up behind his eyes like a map.

A bull the size of a moon shed a snort that stank of prairie tea. Huckleberry hopped, knees stiff, to the right, where the earth dipped into a wallow slicked with last week’s rain. A prairie dog hole offered him a laughably small front door. He snorted back and slid on his old hips into the wallow, belly to mud, chin to dust, tail a comma of white-and-black punctuation.

The herd broke over him. The world became drum and hair and moving shadow. Bodies parted like a river around a rock, and Huckleberry held that rock thought steady in his head. Dust sifted onto his freckles until he was a peppered biscuit. Hoofbeats stitched their thunder on both sides; he felt them in his teeth. A calf flashed by, wild-eyed and frothy-chinned, missing its mother by an impossible inch. Longer beats, shorter beats, a space for breath. He waited, listened, counted, the way old bones count weather.

Silence arrived in ragged pieces. The back edge of the herd unspooled into distance, dust rising like bread dough and collapsing again. Huckleberry lifted his head. His ears were full of heartbeat and meadowlark scorn. He took a breath heavy with bison musk and old sage and the faint, heroic ghost of sugar.

Then came the cry. Not meadowlark. Higher and thinner, a torn whistle. He found it at a rusty fence that pretended a pasture was a decision. Barbed wire had snagged the calf he’d seen, twisted around a skinny hock and biting deep. The calf lay panting, sides racing like the prairie had given it too big a sky and no instructions.

Huckleberry approached sideways, the way you do when someone’s pain is all legs and panic. He wagged once: we are civilized dogs, even at fences. The calf rolled an eye at him, a marble of fearful milk. The wire sang a tight note.

Teeth were tools. He had good ones left, blunt and honest. He set them to the twist. The barb nicked his lip; a dot of red bloomed among dots of black. He shook the wire, worried it like a rat, backed off, tried a new angle. The fence was an old story, but Huckleberry was old too, and old stories could be unbraided if you didn’t rush them.

The calf’s breath came hot on his neck. Behind them the herd muttered, mothers calling calves with the old language of plains and milk, a foghorn syllable that made the hairs along Huckleberry’s spine rise. He dug claws into sod, leveraged his weight, and the twist gave a sighing little surrender. He pulled again. The barb slid, caught, slid. The calf jerked. The wire snapped back like a snake and bit Huckleberry’s ear for good measure. He flinched, blinked at the lightning of it, and returned to the work.

He remembered the bell from the firehouse that used to lift him to his feet no matter what the hour. He remembered men’s boots and horse breath and his job to be calm when everything burned. This was smaller, simpler, true as water. He let the job fill him until nothing was left but the particular taste of rust and the problem of a twist.

When the wire finally spilled its grip, it did so all at once. The calf scrambled, leg free, staggered, and blinked at Huckleberry with the amazement of a creature to whom the world had just changed. It smelled like milk and heat and daisies. It licked Huckleberry’s sugared muzzle—one grateful swipe that took a lifetime—and bawled a word he didn’t speak. Huckleberry stood and made a small circle to prove to his knees that they still remembered circles.

She came for the calf then, the cow with a face like the west end of a storm. She did not rush so much as rearrange the air around her. Huckleberry was not impressed by rearranged air; he had napped under heavier. He kept his line of sight low, eyes soft, tail low and occupied with the serious business of a non-threat wag.

The cow stopped close enough that he felt her breath stir the fritter crumbs on his nose. One enormous eye took him in, mottled and old-seeing. She huffed—the kind of huff that in any language means: noted. The calf put its adorable head under her barrel like a lamp under a porch. They moved off, not quickly, not slowly, just moved, the way the prairie moves when it has done the math and the answer is leave.

The meadowlark came back to inform everyone that this had been very dramatic and frankly unnecessary. Huckleberry heckled once, because one must return heckle for heckle to keep the world balanced. Then he turned his spots toward home.

Home was a short walk if you were the kind of dog who believed that every distance could be shortened by thinking of biscuits the whole way. The path bent past a cottonwood that sang of water no eyes could see and a pile of bones bleached to the color of moonlight. His shoulder ached the way an old hinge sings in a familiar house. He let it. He took what shade the grass offered. He stopped to drink from the stock tank because cold metal water has a taste like coins and summer. On the far hill the bison rippled on, already the memory of weather.

The truck was where it always sat, sunburned red and patient, with the Airstream glinting like a fish pretending to be a building. Junie’s door stood open in surrender to the heat. She’d not gone far; the smell of oil and sugar told him she’d been frying something two parts sinful to one part practical. He climbed the steps like an old porch dog and put his chin on her knee. The knee in question had a flour handprint on it that matched the one on her shirt. She wore her hat indoors because sometimes the day gets inside you and you need to keep your shade.

“You’ve got yourself decorated,” she said, and thumbed at the ear where a spot of blood had dried. The thumb came away freckled with him. “What’d you go and argue with?”

Huckleberry blinked in the manner of dogs who have seen a thing, done a thing, and do not subscribe to overexplaining. He licked the edge of the paper bag on the counter. Junie laughed, a sound with the same temperature as biscuit steam, and pushed the bag across so he could render the grease stains into something more philosophically complete. He chewed thoughtfully. Sugar on his tongue said the wind had done its job.

They sat in the doorway like two pieces of the same porch, watching the prairie put itself back together. Ants returned to their errands. The meadowlark tried out a melody that wasn’t an insult for once. The bison were back to being hill-shaped, the immediacy of them dulled to fact.

Junie scratched the base of his neck the way a person does when she’s counting someone else’s heartbeats because counting your own is too close. “Thought I heard thunder,” she said. “Then I remembered we don’t get rain when we need it. Guess it was those old shag rugs on legs.”

Huckleberry sighed from somewhere behind his ribs. He felt large in the good way, like a thing with purpose. His body had ached and worked and would ache again. His spots were dirty and triumphant. He had exercised his right to remain calm when unreasonable. He had put himself where the world could go around him and not through. He was, in the unfussy arithmetic of dogs, fine.

The light went all honey at the edges, smearing gold on the cottonwood leaves. The horizon lay down its long, flat invitation. Huckleberry accepted it with ceremony, circling twice on the mat beside Junie’s boots, curling into the comma of a sentence that had said what it meant. He thunked his tail once, because joy will out even when sleep storms over you.

As his eyes drifted, the wind tugged the last of the sugar from his whiskers and carried it into the long grass, where ants, larks, and microcosms made what they could of it. The prairie breathed, big and slow. What had thundered had passed. What needed saving had been saved. For an old sheriff of a dog, it was enough. He slept, and for a while the horizon really was exactly what he’d always thought: a long, flat nap, taken by two.