Iron and Old Secrets

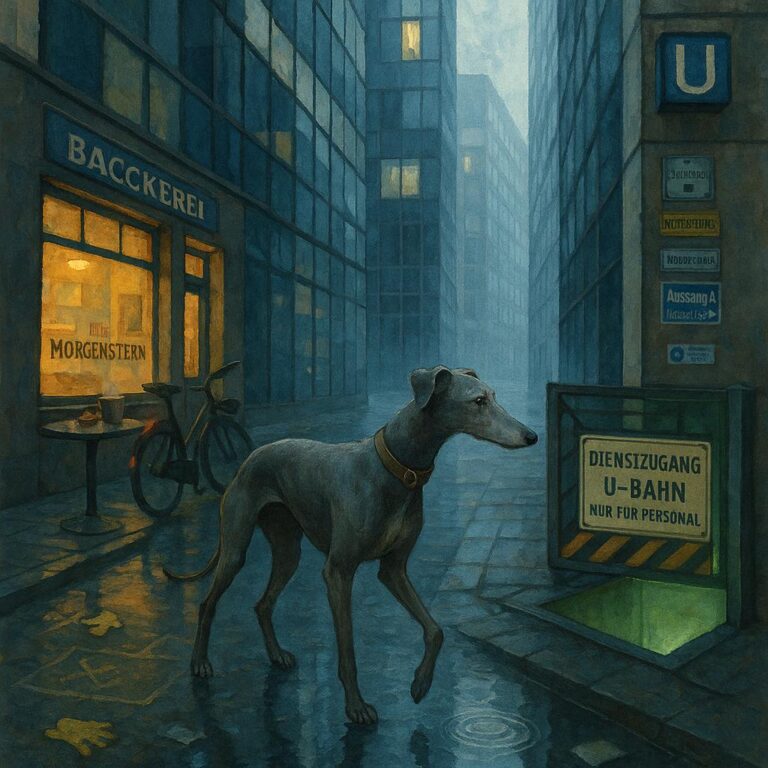

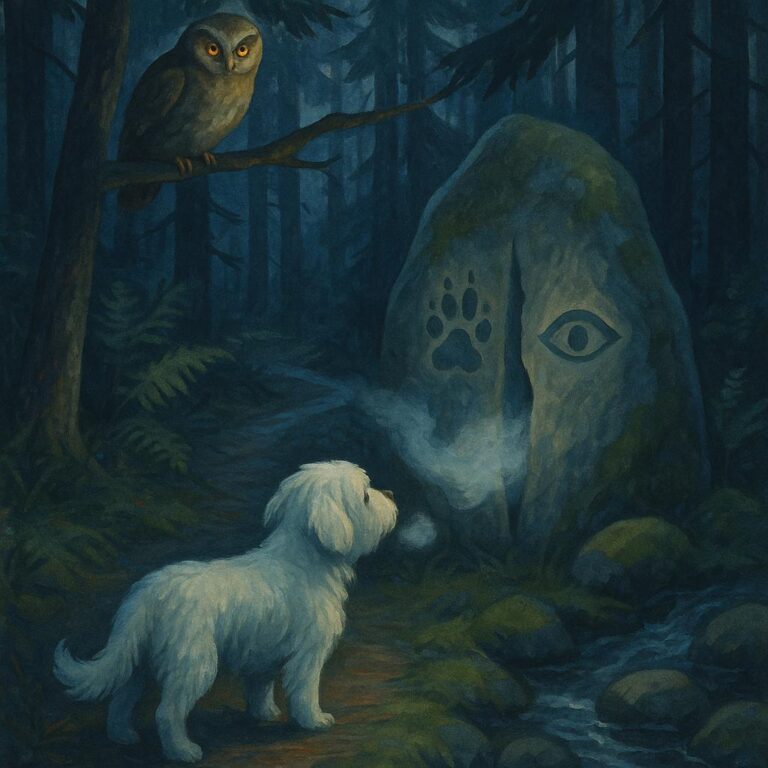

Dawn teased spruce as I, Winston, a fifteen year old Bernese Mountain Dog, padded ahead. I tell the truth of every heart here, because I hear it. Mara’s courage shivers. The fox calculates. Even the moss remembers rain. We follow the lost bell of her brother’s bike deeper, where the air smells like iron and old secrets. I taste thunder before clouds exist. I know the stag will wheel left, the creek will swell, the man with the red cap will lie. When branches snap behind us, I turn, and see the red cap. He raises the rifle toward Mara.

I do not think. I move.

My shoulder slams Mara and she falls into fern. The shot bites bark where her ribs were. Sap leaps out, sweet and shocked. The rifle hums a second song into the trees.

“Hey!” the red cap says, but his heart says different. Keep them out. Hide the hole. Hide the snare. He smells of oil and old beer and a fear with knuckles.

I plant myself between Mara and the mouth of the barrel. I am old, but I am heavy. Mountain is in my name. I raise my hackles until I am taller than I was yesterday. My bark rakes stone from the creekbed and sends it skittering through the man’s boot.

“Winston, don’t!” Mara is a fist on my collar. Her courage shivers, but she does not pull me back. Brave girl.

The man’s hands wobble on the rifle like trout trying to be river. “You shouldn’t be here,” he says. He lies like he breathes. “Hunting grounds.” Lie. “Private.” Lie. “Accident.” Lie, lie, lie. Sweat slicks his lip.

I hear something else. Under the lies. Under the growl of storm still not yet cloud. A thin metal thought, far below. Bell. Not wind. Not fox. The creek swells in the near future. The stag is already running, not because of us, because the thunder I tasted a mile ago is licking his spine.

“Gun down,” Mara says. Her voice slips but she keeps it low, like talking to a spooked foal. Her brother’s scarf wraps her wrist blue and red. “We’re looking for—”

“I know what you’re looking for.” Honest, that bit. It lands heavy in the dirt.

Then the stag wheels left, just as I knew, and the forest throws its own weight into the argument. He erupts out of the brush to our right, a brown hurricane with eyes and bone. He doesn’t touch the man, but he touches the gun. Antler hooks the barrel and flings it into holly. The man yelps, capsized by surprise. He goes down in his knees and the rifle clatters away, drowned in ferns.

Silence falls sharp, except it isn’t silence. It is wind laughing through spruce. It is the bell below. It is the creek remembering the swollen shape it wants to be.

“Don’t,” the man says again, softer. He doesn’t reach for the gun. His heart staggers. There is a picture there: a black mouth in the ground, a board, a nail, a small shoe slipping.

“Where?” Mara asks, all the air in her is a string pulled tight. “Tell me.”

“Turn back,” he says. Lie. His tongue can’t help himself; it was taught that way. But the bell answers for him. It quivers through the roots into my paws. It is scared and trying not to be. It is metal trying to be more than its noise.

I push through fern to the sour place. Iron. Old secrets. Moss remembers rain here and also footsteps that never went away. A rotted plank lays over a mouth. It has a fox’s curiosity of light around the edges.

“Mara,” I say without words. She understands my shoulder when it leans and where my nose points. She drops to her knees and the world shrinks to her breath and the dark below.

“Eli?” she calls. We have not said his name until now because names call things into being. The dark answers with the tiniest glass bird sound. Bell. And then: “Mara?” Thirst and mud and hurt and hope, all inside that two-syllable coin.

The man flinches like a thorn bit him. For the first time his heart tells the same thing as his mouth. “Oh God,” he says. He tears off the red cap and crushes it in his fist.

He scrambles for the rifle and I put my teeth on his sleeve and show him my mountain again. He doesn’t pull away. He doesn’t want the gun anymore. He wants rope. He wants to repair, if repair is a thing you can do after lie upon lie.

“There’s cord in my pack,” he says. Truth. He spins, throws it down, his fingers clumsy. Thunder stitches the sky closer. Fat drops hit the leaves and the creek claps hands in the distance. Everything is coming. It always was.

Mara ties the cord to her waist, then to a birch that grew with the idea of holding tight. Her hands shake as if the wind moved them, not terror. Courage shivers and then sets. She feeds the line into the dark.

“Eli, I’m here. I’m right here.” Her voice is lint she stuffs into the crack so the cold can’t get in.

“My foot,” the boy says. Small. “It’s stuck.”

“Traps,” the man says to no one. His mouth tastes of shame. “Illegal. Not mine.” Lie. “I was going to take them up.” Lie. But I hear the day he almost did. I hear the fence inside him that fell the wrong way when no one would see.

“Help me,” Mara says, and she doesn’t look at him, and he does.

We make a machine of ourselves: birch, cord, Mara, me. I walk backward, chest low, collar biting. I am an old plow dragging spring out of hard ground. The man leans his weight with us, rope over his shoulder. He sets his feet the way someone who works alone does. He winces at every sound from the hole as if it is his own bone.

The board gives up slow, like a secret told by someone who has kept it too long. Wet rot sighs. The hole breathes. Rain stitches a curtain. The creek swells, licking the lip of a culvert, tasting whether it should come in here and drown us all.

“Got you,” Mara says, and her sound breaks when Eli’s fingers break the edge of the world. Small, filthy, bleeding from the ankle where iron kissed too hard. I take his wrist softly in my mouth and pull. He is light as wood-smoke and heavy as alive.

We pull the boy out of the ground and back into the air where his bell and his chest can ring. The cord bites my tongue. My hips complain. Every winter in my joints raises a paw. I tell my bones hush. One more hill.

Then he is out. He clings to Mara and she makes the sound I like best, the laugh that cries. The boy presses his face into her neck as if he could crawl back in and finish growing. He holds the bell that came off his handlebars days ago when fear unbolted it. He rings it once because he can.

The man sits down hard. His face is the color of birch underskin. He looks at the snarl of cord and the hole and his hands like he has never noticed they could be used for either hurting or saving and now he has to pick. “I’m sorry,” he says, and that is the first truth he made on purpose.

Sirens are a long way from here, out where the road pretends this forest is not as deep as it is. The storm decides we have paid enough tax and walks off toward the ridge. The stag is gone. The fox recalculates and chooses mushrooms over mayhem. The creek swells and then thinks better of it and goes home inside its banks. Somewhere, a jay changes his mind mid-sentence.

Mara wraps Eli’s foot with her scarf. Blood blooms like a poppy and then halts under her hands. She leans her forehead to mine. “Good boy,” she breathes. It’s not a sentence. It’s a door that opens.

The man stands with the rope, cap in his pocket. He looks at the rifle in the brush as if it’s a snake that used to be his brother. He nods, not to me, not to Mara, to the choice he’s about to carry. “I’ll show you the other traps,” he says. He will. Later. Today he will walk us to the road by the old logging cut, and he will call the warden himself, and he will wait. I hear it. Truth has moved in him like a new tenant, still unpacking, but there.

We make our way out. The forest shakes water from its coat and pretends it didn’t worry. The moss remembers rain and also remembers my paws, how they pressed and didn’t press again. I take the weight I can from the boy by leaning, warm flank to warm calf. He leans back, trusting. That is the greatest thing in the world. The bell taps my shoulder, a silver punctuation mark to our breath.

At the creek we ford on stones I chose when I was two and when I was ten and when I was fourteen. I know them all by weight and by argument. Today they are slick with the storm’s hurry and I watch Mara’s feet and Eli’s and the man’s. I put my body where the water wants to take theirs, and the water takes me instead a little, and we laugh because I sneeze and because relief makes humans silly and I love them for it.

At the edge of the clearing where the road will be, the light has started to be afternoon. The air smells less like secrets. The fox sits, not close, and blinks at me. We understand each other: calculations, costs.

Mara crouches and puts her hands on my face. She looks into me the way only a few ever have, as if there’s a door and she could open it if she needed to. Eli slides the bell’s strap over my neck. It sits against my white blaze and winks.

“Winston,” she says, “you’re my best mountain.”

I am tired the way stones are tired after holding a house for a hundred years. My legs shake their old song and then quiet. Pain speaks from my hips but it is not the only voice. There are so many voices. Mara’s steady. Eli’s small and bright as a penny. The man’s rough one smoothing a splinter. The forest, all of it, exhaling. Even the moss telling the story of rain to anyone who will put their ear close.

I lie down in the grass with my bell and the taste of thunder gone. The sun finds the place under my ear that always heats first. I smell home like it’s already around the corner, because it is. A blanket. A bowl. The sound of a kettle Mara forgets until it whistles too loud and makes her laugh. Eli asleep on the couch where he was told not to. The man’s red cap on our porch like a flag of surrender. The creek tells me it will stay in its bed tonight, and I believe it.

I keep my eyes on Mara until her shoulders stop shaking and start breathing like a person who remembers how. She lays her palm on my ribs. My heart beats against it. Her heart answers.

I hear all of them, truth braided with truth. And because they are safe, because the bell is no longer lost, because I have carried what I was given to carry, I let the world blur and soften into the weight of her hand. I rest.

The bell on my chest makes no sound. It doesn’t need to. Everyone hears it.