Eighth Avenue Vigil

Keen lights stained the rain on Eighth Avenue as Ishiro, a fifteen year old Akita, threaded the crowd. He remembered snowfields in his first home, yet moved with city patience, reading the air. A courier burned with late fear. A violinist measured hope. Their scents braided into a quiet truth he understood. From a subway grate rose hot metal, pennies, and almonds. Fire. He turned, old bones steady, and drew toward the steps no one noticed. Far below, a small voice called for a mother. The tiles shivered. The lights cut out. The grate under Ishiro’s paws began to lift.

The grate heaved under him like a chest taking a last breath. Ishiro lowered his weight, claws ticking into iron. He let out one bark, deep and clean, the kind that drew eyes without panic. People paused mid-stride, plastic umbrellas stilled. The violinist’s bow hovered. The courier, all wire and worry, skidded back, messenger bag swinging.

“Hey!” someone shouted. “There’s someone—”

Air from below came up hot and sweet with pennies and almonds, the cooked tang of wire. It kissed Ishiro’s nose and burned his whiskers. The small voice lifted again, caught between tile and metal. “Mama?”

The street took a step closer. The courier threw his bag off and jammed the strap through the grate’s lattice, looped it around a bike rack. A pair of cooks in wet whites shouldered in. A traffic cop sank her gloved hands into the iron lip. The violinist lay his instrument case flat and slid it under as a wedge, jaw clenched like he was sighting a note.

Together, they breathed. Together, they lifted.

A thin hand pushed up through the dark seam. Soot traced fingerbones. Ishiro pressed his muzzle to it and let his tongue say what words could not: here. The hand stilled, then wrapped feather-light in his ruff through the grate. The cop took the wrist. The cooks hauled. The courier swore at the weight and added a knee.

They got it open enough to matter. Heat rolled. Light from phones made small moons on tile. Ishiro jumped, old hips remembering and forgetting at once. The gap swallowed him with a clatter. He found the steps no one noticed and took them two at a time, careful and careful again.

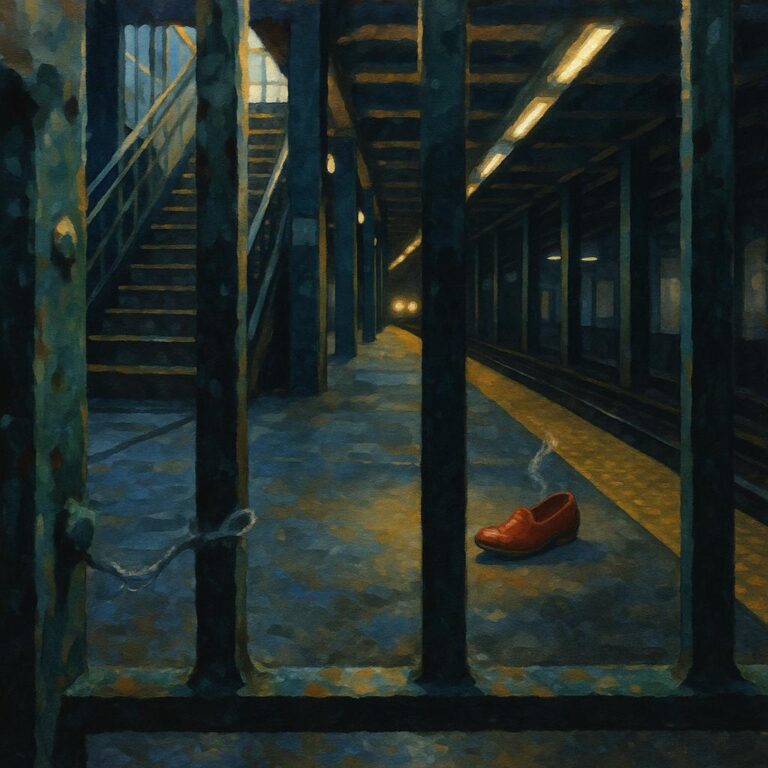

Below, the subway was stopped in its throat. The tiles held their shiver like memory. The emergency lamps failed at corners and came back, butter-yellow. Smoke was thread-fine. The smell of almonds was louder. He moved into it. Through it. He read the ground like a page.

“Here,” the voice said, near the mouth of a service door that stuck. Ishiro pressed his shoulder to it. It rasped and opened enough for a small person to squeeze. A boy with ash in his lashes looked up, rain caught on his cheeks where he’d been crying. Behind him, a woman lay half-curled, one leg pinned beneath a fallen map display. She was breathing wrong and quick.

“Mama,” the boy said, like saying it might do magic.

Ishiro nosed the boy’s knee and leaned, felt the child’s fingers knot in his coat. He walked backward; the boy followed. On the second stair the boy remembered his mother again and pulled, and Ishiro stopped and turned and went back without thinking, because that was the right line in the air. He planted himself against the map, heat warming through his coat. The metal knew his age and did not care. He pushed with shoulder and ribs. The woman’s shoe skidded free. The map did not move enough.

The world above creaked with effort. Boots thumped on the steps. The courier came down with a crowbar borrowed from a hardware store clerk who had appeared out of nowhere like a man from a pocket. The cop followed, radio muttering into emptiness. The violinist came too, not elegant now, just another set of hands.

“On three,” the cop said, and the word three was a promise. They lifted and braced and swallowed the heat. The map came up an inch. Then two. The woman cried out because pain has to seal itself to move. Ishiro slid into the gap and took her hand in his mouth, gentler than you would think a mouth could be. He pulled as human palms slid under her shoulders and her free leg kicked. She came out like a letter from an old envelope, torn a little at the corners but whole.

Up the stairs they went in a strange parade—the boy with his fist in fur, the woman limping and swearing soft into the smoke, the courier backing up, the cop counting breaths, the violinist holding the flashlight high. Ishiro climbed with them and did not look down.

The grate was a square of night trimmed with rain. Hands waited. The city made room. They lifted the boy first, small shoes scratching metal, then the woman, whose eyes found sky with a hiccup of relief. She pulled the boy to her and pressed her face to his wet scalp. She said his name again and again like the taste of it could fix everything. People clapped and didn’t know why their hands were doing that.

Ishiro put his paws on the last rung. His joints spoke to him in old language. The courier, belly flat on sidewalk, reached an arm down that was all tendon and worry. “Come on, old man,” he said, as if the words were a rope.

Heat rifled the shaft. Somewhere far down, something blew like a door slamming in a storm. The grate shuddered in the cop’s grip. Ishiro gathered himself. Not the way he had at two, when the world sprang because he did, but with the inventory of an old soldier. He pushed. His rear paws slipped, found purchase, slipped again. The courier grabbed his collar and the violinist grabbed the courier and the cooks grabbed the violinist’s belt and the whole city became a chain that did not break.

He came up into rain and hands and the boy’s new laughter, high and disbelieving. The grate dropped and clanged, a lid put back on a pot. Sirens began their long blue sentences from blocks away. The smell of almonds thinned and then was gone, chased underground by water and foam and people in coats with letters on the back.

Ishiro shook himself once, head to tail, and the street took a step away to make room for the arc of water and ash. He licked the boy’s knee and the woman’s salt, took inventory: everyone accounted for; fire out of teeth and back in wires where it belonged; the music of the place resuming in small parts.

The woman knelt and put a hand on his chest. Her palm was still shaking from what it had held. “Good dog,” she said, voice cracking. There was the scent of her gratitude, bright and human and animal at once. It was a warm thing. He placed it with the others in himself.

The courier laughed suddenly, that unraveled laugh people make when the end doesn’t end them. He rubbed Ishiro’s ears with coffee hands. The cop wiped her eyes like rain had tricked her. The violinist, quiet as ever, opened his case and lifted the instrument, drew the bow across the strings. A light song the length of one block. It stitched the torn moment without pretending it could fix the world.

Ishiro stood in it. His paws stung, the pads notched a little, but the rain cooled them. His breath slowed. The city’s scents returned to their separate lanes: mustard and wet newsprint, cheap cologne and autumn apples from a vendor who’d never pause, a hundred heart rates steadying into themselves.

Snow came back to him then, from a place further than the train could go. He remembered how it hushed things without asking, how it tucked noise in its white mouth. He remembered the first home where breath made clouds and paws left perfect language behind him. He was the same animal in both places, a thread pulled through time by scent and duty and the simple math of going where he was needed.

The boy pulled free of his mother and pressed his face into Ishiro’s neck, not afraid of the ash. “I found you,” he said into fur that smelled like rain and subway and old pine.

Ishiro stood until the child stepped back into his mother. He stood until the cooks went home to heat and steam, until the courier remembered time and made himself fly, until the cop’s radio filled with instructions that could be followed and the violin’s bow lifted in a last bright note. He stood until the street forgot, the way it must, and became only itself again.

When at last he lay down, it was on the small dry island under the awning of the deli, his chin on his paws. The grate was quiet. The boy’s laughter still lived somewhere on the block, folded into the brick. The rain softened to mist. He closed his eyes to it and let snow come back in the way old things do: not as ache, but as company.

The city breathed around him, steady now. Ishiro breathed with it, an old rhythm he had learned on a mountain and carried down. He slept.