Cold Light on Maple Street

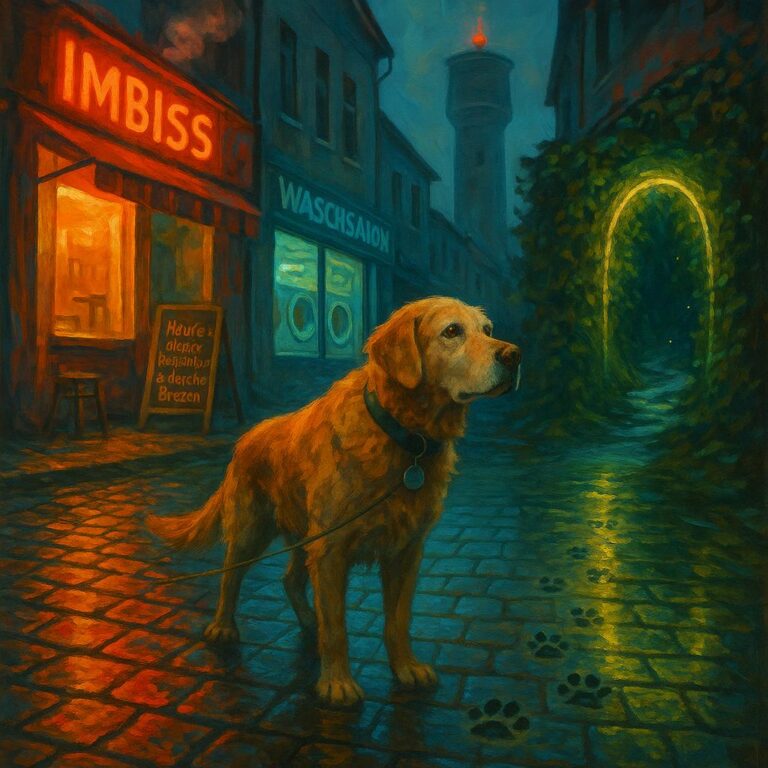

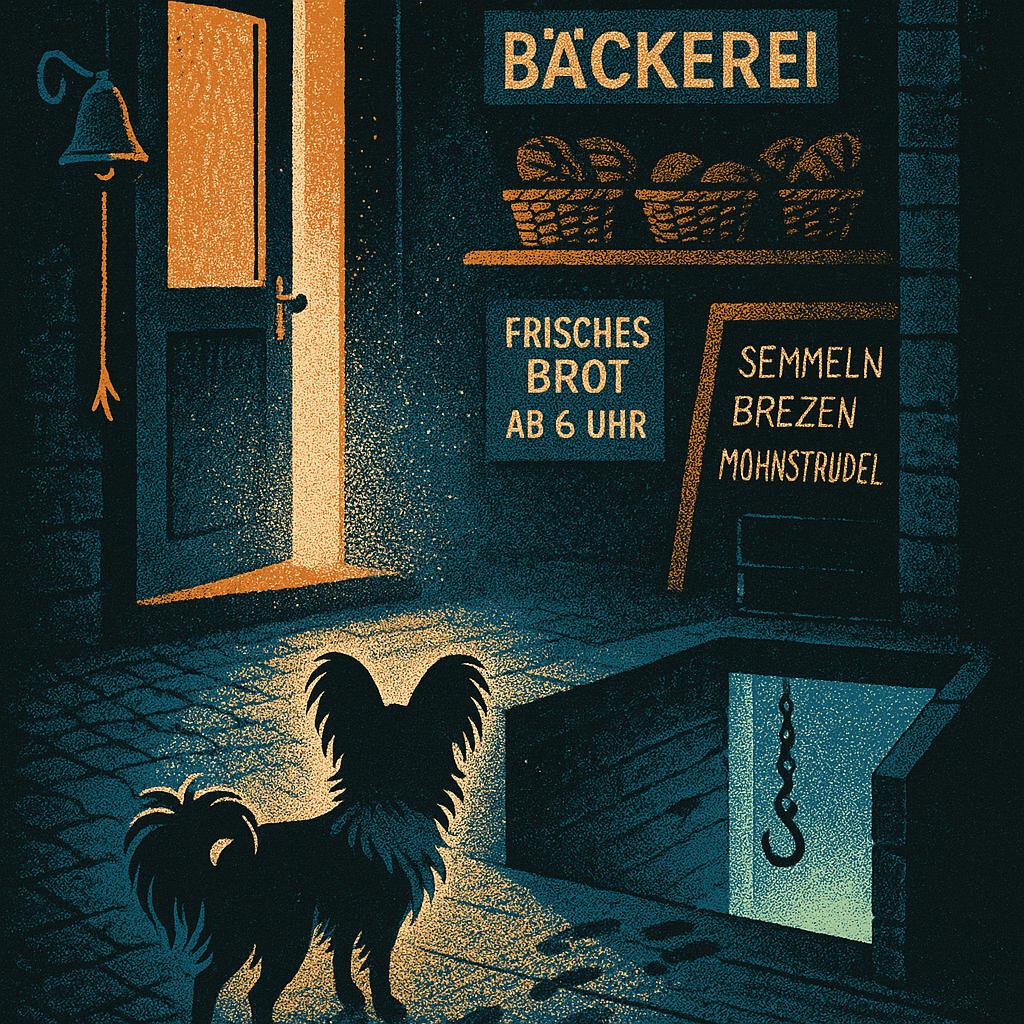

Frost clung to the cobbles as Pip, a fifteen-year-old Papillon, nosed along Maple Street. His hips ached, but the scent was wrong, like metal and rain before a storm. The town had gone quiet after midnight, yet the bakery door stood ajar and the bell rope had been cut. He remembered chasing crumbs there as a pup. He slipped inside, ears pricked. Flour dust shimmered, pawprints circled the counter, not human, not dog. They stopped at the cellar. From below came a clink and a breath that smelled of river moss. Pip crept down.

A cold light flicked on.

The bulb hummed, washing the stone walls in a thin, blue-white glare. Pip flattened against the bottom step. The air tasted of damp metal, of batteries and the river under the bridge.

A man stood by the shelving, coat slick with wet and flour dusted across his sleeves as if winter had touched him too. Waders creaked when he shifted his weight. In one hand, a knife, thin and sharp like a fish’s spine. In the other, the lip of a stoneware crock. The crock had an old linen tied over its mouth. The cloth was dark with years of use. It breathed, faintly, sour and sweet.

Something flicked along the floor. It was low and sleek, whiskers lifting, small black eyes bright in the light. Not a cat. Its feet left the prints Pip had followed, little hands that weren’t hands at all. Otter. River come walking.

The otter’s head turned when he smelled dog. He made a chitter, a question. Pip stared back and knew the river on his fur—snails and cold weeds and iron rails gone soft with rust. The otter tilted his head, not afraid, only curious.

“Quiet,” the man said, not to either of them, only to the cellar itself. His voice came through a scarf, thick. He set the knife down, carefully, the way one puts steel where it can be found again fast. Gloves squeaked on stoneware. He cut the knot in the linen and peeled it back.

The smell rose. Life. The old starter had the river in it, too—not its moss, but its history. Pikestaff and barge, noon sun on ferment, baker’s palms kneading. It breathed in little ripples. Pip had licked spilled dough from these steps when his ears were still too big for his head. He licked his lips now and felt the ache run through his hips like cold.

Pip let out one sound. Not bark. Not whine. The sound a door makes when you open it in winter—wood and swallowed air.

The man flinched. The otter darted sideways. The knife clinked as it spun on the table and fell, the slice of it ringing in the concrete like a bell that had not been cut.

Pip moved. He had no speed left for running, but he had every corner of this place mapped behind his eyes. He pushed at a stack of tray lids with his shoulder. They teetered, then cascaded, bright tin raining. The man swore. He reached for the crock, arms wide to keep it from spilling. Pip went under him, through flour fallen on the floor, through the ghost of a hundred loaves ground fine as fog. His paws were silent. He put his teeth into the linen at the crock’s side, not the jar, not the living thing. Linen was familiar; it tasted of rinsed salt and sun.

His jaw screamed at him. He held.

“Hey!” the man said, and grabbed at the crock. Glove against cloth, cloth against old porcelain, Pip against the weight of his own years. He dug in. Nails scratched stone. Somewhere above them, a truck passed, and the iron belly of the oven upstairs pinged as it cooled.

The otter watched, head moving with the draw and pull. Then, like water deciding, he slid along the floor and knocked his shoulder into the man’s calf. Not hard. Just enough. Waders lost purchase on the flour. The man went a little sideways. The crock came toward Pip as if offering itself. Pip took two steps backward and felt the first stair under his paw. He pulled, breath sawing singed wool through his throat. The crock lifted enough that the bottom scraped rather than cracked.

They climbed like that, man grabbing, dog setting every ounce into the strap, otter reappearing and vanishing along the side of the room as if tracing the current of their struggle. The knife gleamed on the floor, forgotten.

Noise saved him. Tray lids still spun and clattered. A spoon, disturbed at last, rolled in a circle near the drain. It sounded like a bicycle bell that had lost its owner. Up top, someone woke. A window slid. On Maple Street, voices came together and broke apart again: Did you hear that? What is that? The bell rope—who cut it?

Pip backed out of the cellar, one stair at a time. The first scrape brought the crock to the landing. The second lifted it to the level of his old paws. The man lunged and hit the post with his shoulder. A bag of sugar went with a soft thunder, burst against him, and made him a ghost. He coughed into his scarf and coughed again, eyes running, arms white.

Pip dragged. The linen burned his gums. Old teeth moved in their beds. Upstairs was night and flour in the light like snow. He could smell the door, the hinge, the street beyond. He could smell warmth far away, like a memory someone else was having and he could eavesdrop on—bake to come, even if it was still dark.

He reached the counter. He couldn’t jump. He leaned and slid the crock onto the flattened sack of flour, and it sledded a little to the far side. He planted himself in front of it, legs braced, little and certain as a doorstop. The man came up, white as bread before crust, knife forgotten in the cellar now. He saw the place between dog and crock and another thing came into his eyes, the kind that isn’t about food. It was the kind men get when they’ve made a decision and can’t unmake it without unraveling more than rope.

The back entrance rattled. The night watchman’s key knows every lock in town. The door gave, and cold, clean air moved like a new page turning. The watchman filled the doorway, the baker behind him in a coat over pajamas, hair up in a cap without thinking. The baker smelled of coffee and exhausted worry. The watchman smelled of wool and nickel.

“Joseph?” the baker said. The name landed heavy.

The man swallowed. He took a half-step back and left a print that would never match any shoe. It was the sole of a wader, not a human sole at all, broken into pads like a paw.

“They’d pay,” Joseph said, muffled. “For the mother. In the city. More than the season’s take. You know it. We learned it on the river. You did. I did. Wild yeast keeps you alive or it doesn’t.”

“You cut my bell,” the baker said. His voice wasn’t loud. It didn’t have to be. The watchman moved forward. The otter slipped past his boot and he flinched and lost a little of his importance.

The watchman’s hand was on Joseph’s arm before any more words could come. Waders squeaked again. Sugar turned the floor treacherous. Joseph sagged, sat down on the burst sack, and watched his hands sink into it as if snow could dissolve a man from the bottom up.

The baker crossed the room and went first to the crock. He put his palm near the linen like a blessing that did not touch. He looked at Pip then. You might think eyes would go young when they filled, but his didn’t. He was an old man looking at an old dog. He crouched until his knees cracked, and he put his hand against Pip’s cheek where flour had mapped new freckles on him.

“Good lad,” he said, no louder than you tell a secret to a baby. He smelled of coffee more now. He stood and took the crock into his own arms, held it like a child he had once lifted every morning.

The watchman said the things watchmen say. Joseph said the things men say when the night has gone on too long and chances are used up. The otter, finding no water, nosed at the corner of the sugar and sneezed. The watchman made a little noise and the otter made another, and in the confusion of it he slid through the open door into the street. He flowed toward the alley and the drain grating there, where the town met the river, and did not look back. The night took him and kept him, as was right.

They led Joseph away between wool and wool. The baker locked the door. He took a broom to the sugar, moving snow back into the drift from which it came. He set the crock on the counter where Pip had never been able to go, high and safe. He tied fresh linen over its mouth. He checked the knot twice. He went to the corner where the bell rope should have hung and climbed on a chair and threaded a new line. His hands remembered. The bell on the door gave a small, suitable sound as if clearing its throat after a bad dream.

By the time the eastern edges of roofs turned from black to metal to pearl, the bakery had heat again. The oven woke, stretching iron and sighing, its smell turning from cold ash to warm. The starter lay down into the flour with water and salt as if returning to bed. Hands turned and folded and pressed, and the room filled with the slow thunder of working.

Pip curled under the table where he had lain a thousand mornings. His hips talked about everything they had done as old hips do, a list and a list. The first loaves went in. The oven door shut like a promise. Maple Street breathed. The smell that was wrong, the one like rain before a storm, went thin and then was gone, left behind by crust and butter and the sweet, clean steam of yeast doing what yeast does when it’s safe.

Someone laughed upstairs, a tired, shaky noise. The bell chimed as the baker’s wife came in from the back with a blanket. She laid it over Pip without asking because she had always known where he’d be. Flour fell from the blanket in a drift and he wore it like he had grown whiter in an instant. He licked one paw and then the other and tasted sugar. He closed his eyes because then he could see better.

Later, when the town woke properly and the door opened and the bell spoke and there were boots and small shoes and a child’s mitten forgotten on the counter edge, the baker tore the heel from a still-warm loaf and let it cool on his palm. He broke it into a piece the size of Pip’s mouth. He held it low. Pip lifted his head and took it gently, as if returning a borrow.

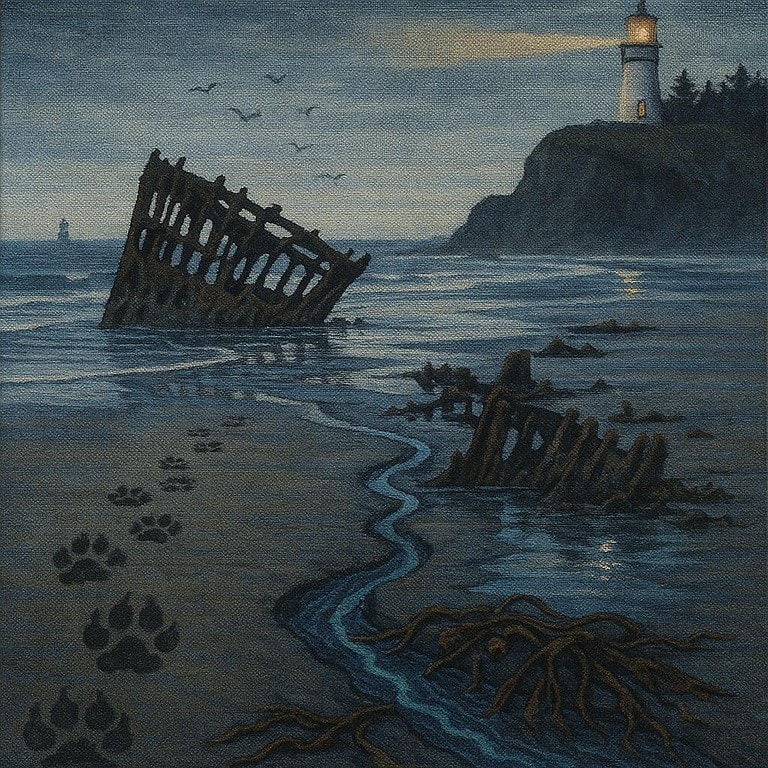

Outside, frost let go of the cobbles under the slanted sun. The river moved as it always did, taking and taking and giving back in smaller ways: damp air, a reflection, a scent on the breath of an old friend who had come to steal and had left with nothing but a set of prints that didn’t belong in a bakery. Upstairs, the new rope swayed when the door touched it and the bell made a clean, decent sound. Pip slept, and in his sleep his paws moved a little as if they remembered stairs. He dreamed of crumb and warm light and cool water that stayed where it belonged. When he woke, the day had started, and the town smelled right again.