Bram, Come Home

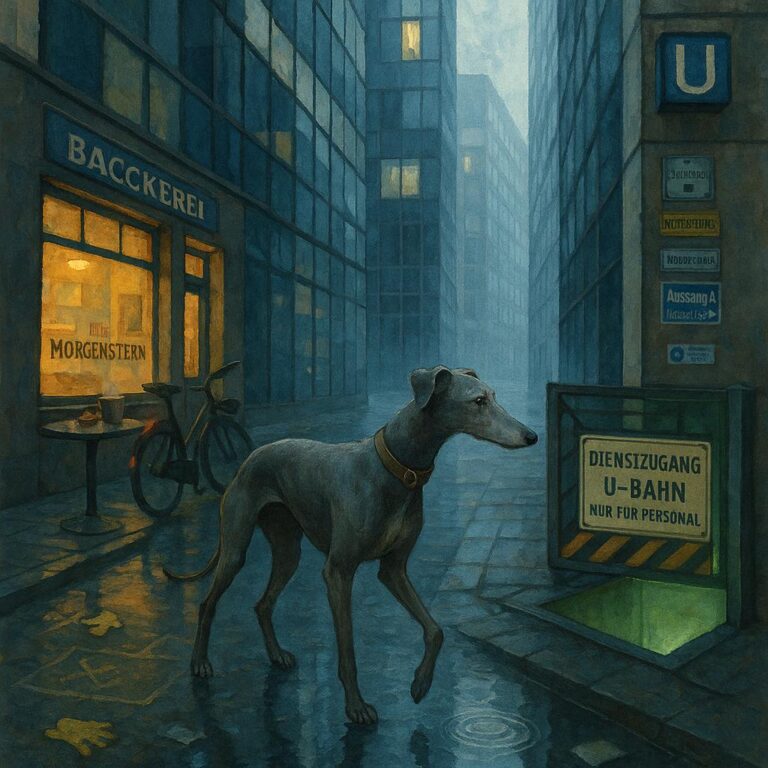

From the moment moonlight pooled on the cracked flagstones, I, Bram, a fifteen year old Brussels Griffon, felt the castle breathe. Drafts ruffled my whiskers like unseen paws. Portrait eyes followed my shuffle along the mossed corridor toward the barred chapel. Bells that had no ropes chimed once. I nose pushed the rusted gate and it yielded. The scent of my long gone master rose warm as summer, threading through cold stone. Then a soft voice, shaped exactly like my bark, whispered behind me, Bram, come home, and the gate slammed shut as footsteps descended the stair.

The steps were not heavy ones. They padded as I pad, delicate, sure, familiar to my ear as the beat under my ribs. The smell rose again—sun-warmed wool, saddle soap, the apple core my master used to hand me to worry in the orchard. There was damp stone too, and old beeswax, and somewhere far off the green, sweet leak of the moat.

The chapel was bones and cold, but the air around me softened like lap furred by many nights. Candles that had no wicks gave a low light. I did not growl. My tail made a single metronome tap against my hock. I knew that gait. I knew that patience.

Bram, the voice said once more—my own bark folded into a word the way he always did it to tease me. The barred gate had clanged behind me, but the iron between the nave and the chancel had a dog’s gap and I slid through as I always had, ribs scraping rust, whiskers combed by old iron. The chapel heart opened. Stone knights slept with their paws on their swords; angels with sand-worn noses watched through white dust.

He waited not on the slab, but on the shadow the slab throwed. Boots that would not stain with mud. A hand that did not stir the air and yet pressed the top of my head into the right shape with a memory I had carried in my skull my whole life. He smelled like July. He smelled like the first time he said my name and meant it.

I burst into a trot without pain catching my hip. The ache that had been mine for two winters fell off like a burr brushed out. My nails, blunted from years, struck the stone with a young, sharp tick. I made a circle, then another, to show him I remembered the right way to greet. He laughed, the sound cut with my own yip, and bent without bending.

There were stairs down behind him. There had always been stairs down; they had always been closed. Now the dust lay divided into two neat lanes. He went first as he always had, quick, looking back to see that I followed, and I followed as I always had, chest out, ears pricked, my body making itself wider to guard his heels from any rat or rumor.

Down there the castle breathed different, slow and warm like a hound sleeping. The walls were damp and tasted of iron when my tongue ran over them. Names hummed in the stones, hundreds of names, all of them said the way he said mine: knowing the shape of me.

At the bottom, a wooden door leaned drunk in its frame. He pressed it with the side of his leg and the dark beyond uncurled. I could smell grass, not the sick February stubble above, but the lawn that remembers chasing and laughter. Apples were piled against the doorway although no tree could have grown here. A brass bowl sat level, full and still, and I recognized the dent from the time I had stepped in it and been forgiven.

Come home, he said, and I saw what home meant—my bed before the fire, the weave of his coat against my ribs, the sound of his violin bowing low and my own small dream-woofs breaking it. I did not have to be brave. I had only to do what I had always done: climb where he climbed, lie where he pointed, keep watch.

I went to the brass bowl and drank. The water tasted like the first time and every time after. It went right through me and took the stiffness with it. When I lifted my head, he was sitting on the step with his hands on his knees, making himself small so I might reach him. I put my chin in the place above his boot where the leather creased. His fingers found the place behind my ear that had made my foot thump for fifteen years. My foot thumped.

The bells rang again—twice now—and, far up where the moon had been, morning laid itself across the ruined windows. Light found the chapel, turned the dust to gold, and ran cool fingers over the iron that had barred me. The gate unlaced its teeth. The portraits, for once, looked somewhere else.

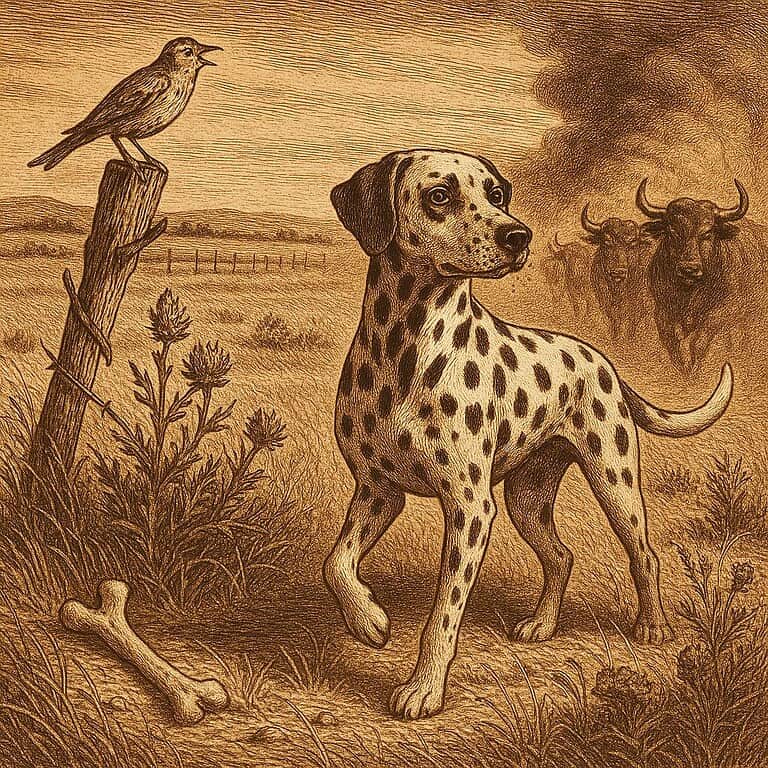

Do you remember the orchard? he asked.

I remembered. Bees slow with bloom, my teeth sunk carefully in fallen fruit, his laugh when I sneezed pulp. The path under the hedge I wore just wide enough for a dog, the way the world smelled like green and sugar and a man who was mine.

We went back that way—through a door under the world that opened not on bone and stone, but on grass. The castle stayed behind us like a coat shrugged off. I did not look over my shoulder. I did not need to. I knew every draft and sigh and wardrobe of its heart. I had kept it, as I had promised. I had waited until the call came in my own bark.

He kept a pace I could keep. My chest did not rasp. My paws did not turn under. When he ran, he ran just far enough that I could catch him, and when I leapt, I caught the cuff of his coat and was scolded, and the scold was love.

By the time the sun was full on the east face, the morning caretaker found the chapel gate swung open and muttered about hinges. He touched the iron and it did not bite him. He saw the little bed near the altar that sometimes had a blanket on it, empty, the blanket smooth as if pressed by a careful hand. He saw paw prints in the dust leading to the chancel rail, and beyond that, nothing at all.

Up in the orchard that no longer grew, where only nettles should be, a sweetness lifted like breath. A small red dog’s bark, thin with age and strong with joy, threaded the air once and faded into the kind of silence that keeps. In that quiet, if you pressed your ear to the ground and did not mind what your trousers suffered, you would swear you heard footsteps, four and two, going on together.