The River That Knew His Name

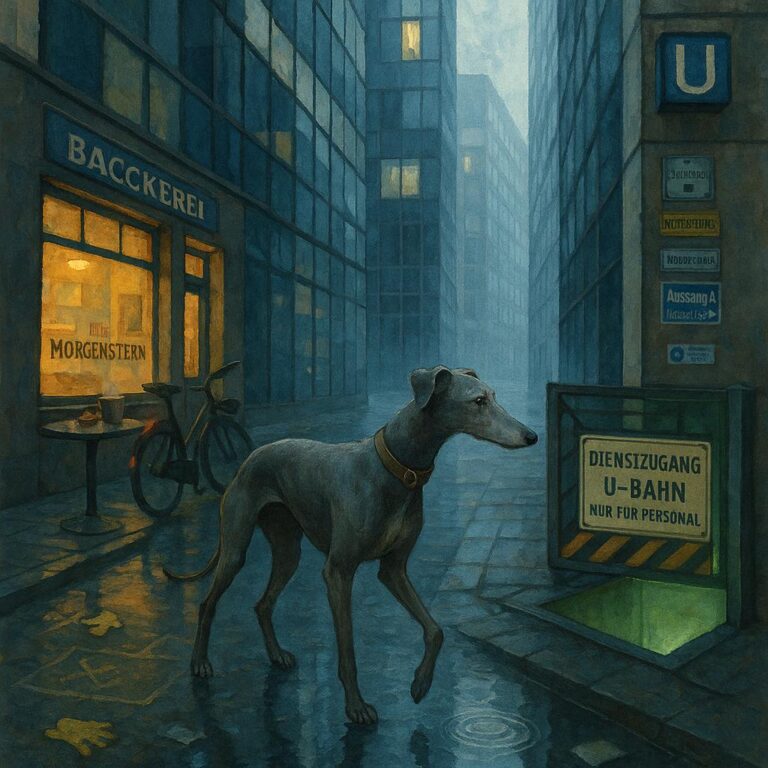

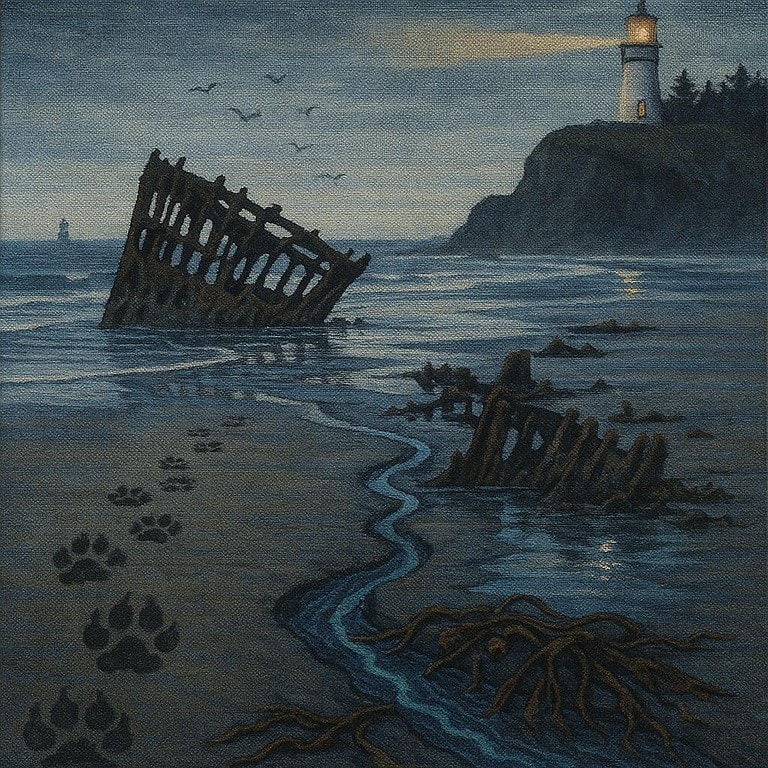

Mist clung to the riverbank as Lumen, a fifteen-year-old Blue Lacy, padded along the pebbles. He felt the ache of seasons in his bones, but his nose, wiser than eyes, sensed a trail of cold iron and lilies. The river knew him; it had watched him since puphood, and tonight it whispered in eddies only old ears could catch. A silver glimmer drifted against the current, a collar just like the one he lost years ago, rattling with a tag that read his name. The water tightened, stilled, then parted. Something stepped onto the stones, wearing Lumen’s other scent.

It stepped into the moon-sheen and it was him, only unscuffed: a blue hide taut over quick muscle, eyes river-bright, paws that hadn’t yet learned the careful set of old ankles. The smell of it was all beginnings—sun-warm rope, milkweed sap, the hayloft on a June noon, the copper bite of blood from a first thorn and, threaded through it, lilies. Not the garden kind. The kind that find their way into water, opening pale as if to catch starlight.

They stood with the pebbles popping under their weight and studied each other, head to tail, tail to head, trading histories in breaths. The newcomer’s ears pricked; he dipped into a play bow that made Lumen’s own forepaws tingle with ghost-memory. It was a bow from a time before lightning scars and before the gentle ways people bend to scratch you stiff as a board because they’re scared of touching something that won’t be there one day. Lumen’s back legs argued, but his chest lowered anyway, a careful fold, and for the laugh of it he swatted at the collar glimmering on the rocks.

The tag sang two notes he knew by the old porch step: thin metal on metal. Lumen nosed it. The letters were the same he’d chased when he was small—up and down, a river of lines that meant Lumen because he was the one who found light when it rolled beneath the truck the first night he ever heard his person say “C’mere.” He knew those sounds as surely as he knew where rain was born. The collar smelled like cold iron and lilies and river stone, and underneath all of that it smelled like his own chest fur warmed by someone’s palm.

A breeze slid cold under his ribs and the young him flicked his eyes to the upstream bend. There were stories hanging there, strung like burrs in the grass. The water held its breath. Lumen took a step, and the younger set off beside him, close enough that their shoulders nearly brushed.

They traveled the shallows where the current ran satin over stones. At the first bend the river threw up a picture with no color, only smell and muscle and sound. Fence posts burned by June sun clicked against each other as a calf broke from the herd. There was the slap of leather and a whistle he knew better than words. He and his young self turned in perfect mirror and cut that little panicked body back into the moving mass. He felt the tight joy twist in his belly, the exact beat of running under a sky that went on forever. He felt it and then it was gone, because the river does not stop.

The next bend carried thunder. He saw himself younger still, a skinny thing, fly off the porch when the first big drop hit the dust, because storms held his name and he’d chase them to the fence and back while his person called, laughing, “Lumen!” until the laugh turned to worry as the lightning came closer. Lumen watched the flash hit the far cottonwood and remembered the way the world smells when it’s opened like that, iron and green and the black after-flavor of something ending. He remembered losing the collar then, or maybe it had been another storm—years ran together like muskrat paths. The water had taken it from his throat in one easy pull, swallowed the jingle, kept the name.

They waded on. The river gave him a cattle guard humming under his pads, the oily perfume of farm hands, the clean sting of winter, and a smaller smell he didn’t know then but knew now: a baby’s blanket dropped on the grass by mistake while the family had a picnic by the low concrete bridge. He had laid on it until someone noticed, because that was what you did for small, helpless things. The blanket had smelled like apples and milk, and it had made a place in him and stayed.

Upstream the water slipped wide and calm, and lilies showed themselves at the edges where the mud was thick and the shallows were warm. Their faces were moons with soft hearts. The young Lumen jumped once at a frog and missed on purpose. Out of habit the elder watched the bank for coyotes, caught only the sour drift of fox, the ghost of a raccoon that had died and gone to become leaves.

He didn’t see his person at first. People don’t show up to noses like dogs do. They come as a braid of things: the nicked leather of a riding glove, the coffee she’d tipped onto her sleeve on long drives, soap, rain-soaked wool, callused palms. The braid tightened somewhere ahead. Lumen’s tongue went dry. The young him lifted his head, and his tail moved in a slow, respectful wind.

There was no body waiting, no boots, no shadow standing tall. There was a shape made from the scent braid, perched on the old fallen cottonwood that the flood had dragged here God knows how many springs ago. The river leaned in to listen. It seemed to Lumen that every night a person sits out alone, rubbing the seam of a cap, certain she hears the dog’s toenails clicking back up the porch—that is where the river put them now, him and that ache together.

The tag on the collar rattled once against stone. The younger turned and looked at him. His eyes were the good kind of empty: not hollow, but open as a winter field, expecting snow. Lumen’s whole body had been aching for months, seasons stacking inside his joints like slipped stones, but right then he felt something loosen, as though a long-held fetch had finally come to hand.

He nosed the collar’s leather. It slipped smooth over his head in a slow, patient circle. The cold iron lay against his throat. The lilies’ breath rose up around him as the water shifted, as if someone exhaled after a hard day, as if the house lights clicked off one room at a time. He stood between water and bank wearing his name again and the years that name had traveled.

The young Lumen came in close, shoulder to shoulder at last, their ribs making a hollow between them where warmth pooled. Lumen took in the young one’s smell one last time, the way you inhale hay deeply before the stack is gone for winter, knowing exactly what you’re losing and not afraid. Then the young dog moved, not away but into him, not in anything so showy as light, just in a rearranging of scents and heartbeats. Lumen’s next breath was bigger. Not stronger—bigger, as if there were room in it he hadn’t had in a long while.

They turned downriver together, towards where his porch lay—the one with the step that popped because of the swollen plank, the one whose boards kept the day’s heat for an hour after sunset. The river didn’t reach to the house; it made a promise, the quiet kind, that it would run under his sleep.

He climbed the bank in the same careful way he had come, paws learning each rock, the tag giving a soft music that the frogs folded into their own. He trotted the dirt lane and the driveway gravel, slower than once, but with that old straightness of purpose. The porch knew him by weight. It sang its old pop when he put a foot on it. He did not go to the door. He put his shoulder where his person used to sit with the world on her mind, where dust and sun had made a small warm hollow against the siding, and he lay down there. He set his chin so the collar’s tag touched wood.

Night touched his ears. A whip-poor-will wrote the same word again and again at the yard’s edge. Somewhere a bottle fly worried at the screen. When the house shifted, it said things to him it had been saving up. Thank you. No more chasing storms. Sleep.

He let the sounds come and go. He let the smell of lilies and cold iron fade to a thread and then to nothing. Dawn gathered itself on the far side of the field, pink behind the oaks. It arrived first as a change in the kind of dark. In that paler dark, with swallows drawing commas out of the air and the house giving one last sigh, Lumen’s breath went easy and then simpler. The tag tapped once, then was quiet.

The river, having returned what it had kept, went on doing its oldest work, shouldering round stones, carrying news downstream. On the porch, in the small warm hollow, there was only a dog-shaped stillness and the faintest scent of lilies where his name had rested. When the sun found it, the space filled with light. The light had a name. It had always had one.