Heartbeat on the Ridge

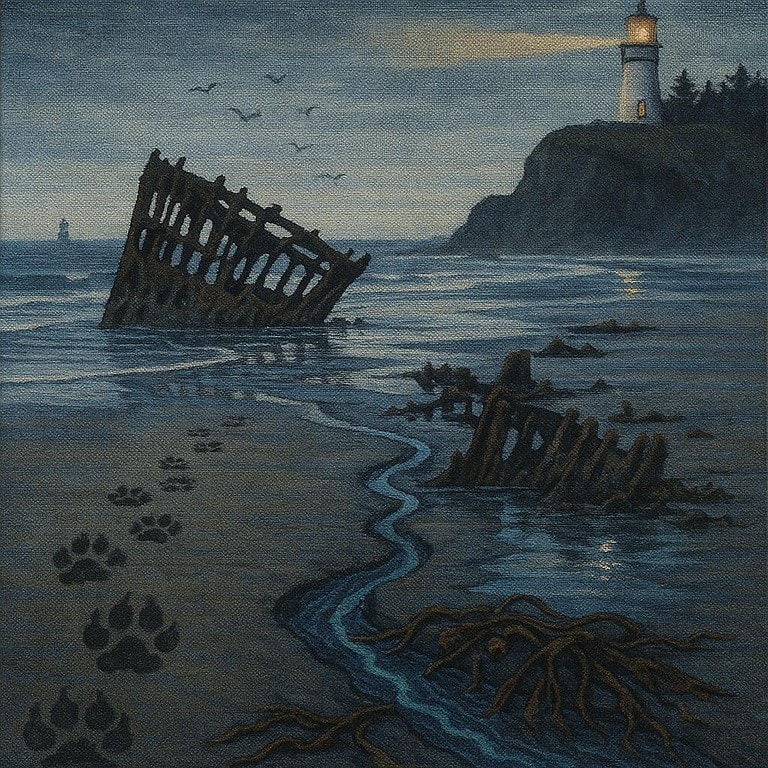

Hushed twilight softened the valley as Harlow, a fourteen-year-old Siberian Husky, lifted tired paws through meadow grass. He remembered winters of flying snow and the warm laugh of Mira, whose hand still found the gray along his muzzle. The river turned rose, and the valley breathed a vow around them; even the hawks circled slowly, as if blessing a promise Mira had hidden in her pocket. Harlow caught it first, a scent threaded with wildflowers and years ago. Not Mira. Not river. A familiar heartbeat on the wind. He looked up, ears pricked. At the ridge stood…

…a small, dusk-colored husky with one ear bent and a milk-blue eye, standing as if the ridge had grown him there.

The scent unfurled the way a song returns—thin at first, then full, then unmistakable. Milk-warm den straw. Birch sap. The breath of a mother long gone. He did not know this young body, but he knew its heartbeat like a bridge he’d crossed before and could cross again without thinking. His chest shook not with age but with recognition, and he gave a sound he hadn’t made since the last snow of his first winter: a low, hopeful whuff.

Mira’s fingers found the space behind his ear. “Go on,” she whispered, as if he were still the young fool who didn’t need telling, who would have bolted straight up that slope with no thought for the thorns. Her other hand stayed in her pocket, the promise warm and small there, waiting.

The young one stepped down from the ridge, deliberate, toes spread to feel each rock. Halfway, he stalled, head angled, nose lifting to weigh the old stories riding the wind. Harlow stood still so as not to frighten him, letting the boy take measure of gray hairs and slowed breath and scars beneath fur. He kept his tail loose, his shoulders soft, and when the boy finally drew close enough to smell the truth of him—the river and the woman and the thousand miles that had carried them here—Harlow lowered his head and pressed his muzzle to the youngster’s forehead.

The ridge let out the breath it had been holding. Grass leaned and whispered around their legs. The hawks circled lower, like coins flipping in the sky.

A small whine trembled against Harlow’s teeth. He answered with a puff of air that said yes without needing words. The boy’s tail wrote his whole heart, a clumsy eagerness, and Harlow felt the old joke lift in him, the one he used to play on bolder pups: the lean-and-bow, weight on front legs, a lick’s breadth of a dare to chase. It had been years since his ankles trusted dirt that way. He did it anyway, and when the boy sprang, Harlow turned and let himself be chased for a few strides, not far, just enough to feel winter again, just enough that Mira laughed out loud, the laugh that had kept him from breaking during storms.

No tether, no command. Just three bodies in a meadow and the river storing the last of the day’s fire.

They came to rest under a straggle of alder that had survived floods and cattle and careless campers. The boy nosed Harlow’s paws, mouth soft, tail busy. Harlow licked the boy’s whisker spots as if blessing them, then glanced at Mira, who had not moved, because she knew sometimes you ruin magic by stepping too close.

She knelt when he looked, the way she always had, so that her face was level with his and he could see the mark of years in the skin at her eyes, and love in the new lines there, too. She drew her hand from her pocket.

On her palm lay a small bell and a circle of leather gone smooth with time. The bell had rung one winter through white-out that tasted like metal and fear, when the man with the voice like cracked ice put Harlow at lead for the first time. Later, when the man was gone and Mira had brought him home, she’d tied the bell to their kitchen window where it caught sun for fourteen summers and called him for dinner. He had not heard it against his own collar in years, because some sound belongs to then, not now. He had thought maybe they’d buried it with the first friend who’d known his name. But Mira had kept it. The promise.

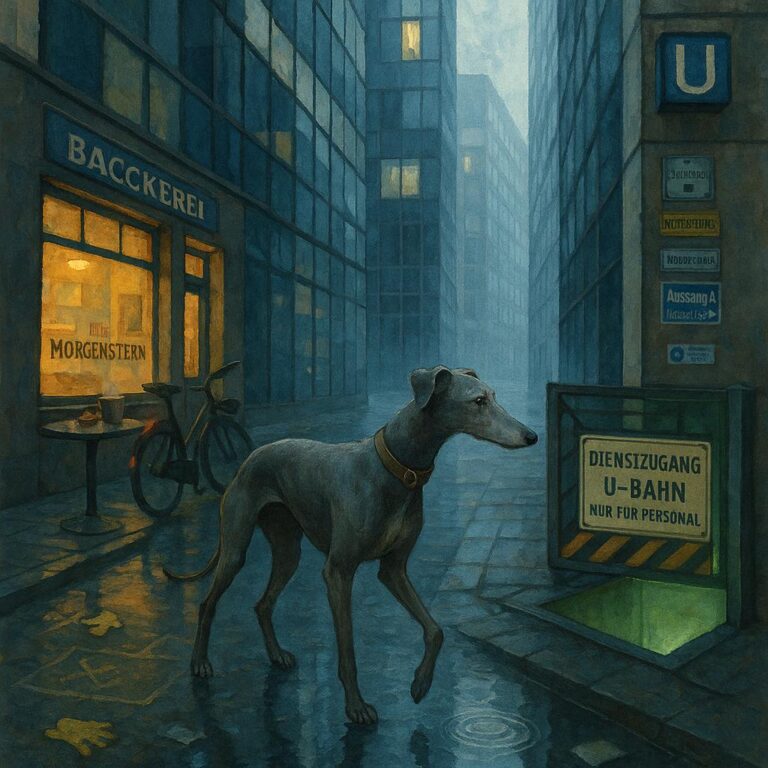

“She’s called Rowan,” Mira said. “Your girl from before had a daughter after you left, and she had him. Her people moved to the hills, and their boy starts at the fish plant next month and won’t have time. They said he needed someone who knows snow. They sent letters. We found them.”

Rowan. The boy lifted his head at the name as if it tugged on a string attached to his ribs. He looked over the valley as if expecting it to answer back. Harlow pressed his shoulder to Mira’s knee, listening, understanding—not the words, but the shape of them. Not your blood, and yet.

Mira slid the leather through her fingers. “If you don’t like the bell, we won’t,” she told Harlow. “Maybe we keep it on the kitchen window. Your choice.”

Choice was a funny thing. For years it had been given to him in the smallest ways—the side of the couch, the pace on a walk, the spot to sleep near the radiator. Bigger choices had always belonged to weather and humans and the simple math of eating and being warm. This, though, felt like something he could answer.

He leaned in, and Mira’s hands did what they had done a thousand times: buckle, check, snug. The bell sat at the hollow of the boy’s throat. Rowan shook his head and froze, startled at the sound, then chased it in a circle, ears up. He looked at Harlow, asking. Harlow sniffed the bell, then the boy’s cheek, and brushed his face along it as if to say: That sound will be us. That sound will mean home.

They took a slow loop to the river, Harlow setting a pace that respected rocks and knees and old aches. Rowan tried to match it, overshooting with puppy zeal, then checked himself, eyes cutting to Harlow for correction, for yes and no. Harlow gave him both as needed. Go around the thistle. Keep your head when the hawks shadow you. There, where the water mouths the bank—don’t step, it slides.

Mira walked behind, and when Harlow looked back, she had the expression she wore when she finished a hard thing in the woodshop and knew she had gotten it right even if nobody else could name how or why.

They came to the place where the river bent and softened around a gravel tongue, a spot that had been theirs and nobody’s for a long time. Harlow went to his belly with a groan that ended in pleasure, front paws long, chin on his wrist. Rowan copied him so exactly that Mira had to sit down in the grass to laugh again, tears in it this time. The boy put a paw over Harlow’s, a clumsy claim. The bell made a small sound on the stones, bright as the river talking to itself.

Evening collected itself. The hawks were black loops now against lavender. Somewhere up the slope a fox yipped, and Rowan tensed, and Harlow breathed patience into him without moving, the old lesson: some calls are not for you.

He found himself remembering a winter with no end, when hunger was a small god and the only prayer was forward. He remembered the first night Mira let him sleep at the foot of her bed, the way her feet had shifted in the covers to make space for him, as if she were shaping snow with her toes for his body. He remembered the squeak of his mother’s ribs under his ear, and the way dawn smells when it has promised you something. He remembered and did not hurt from remembering.

Rowan’s heartbeat settled against his foreleg, steady now, not the hummingbird of earlier. Harlow turned his head and mouthed the boy’s ear just enough to say, You hear that? That’s the sound you keep. Whatever else changes, keep that.

When at last they rose to go, the first star had stitched itself above the ridge. The valley was a room with the light turned low. Harlow went first, which he had not done in a while—not because he had to, but because it fit the moment like the collar fit Rowan’s neck. Down the path, across the meadow, through the gate Mira had mended with wire and patience. Their shadows braided and unbraided with the grass. The bell was a small heart that took up no space and filled the whole field.

At the porch, Harlow stopped and looked back. The river had turned to silver string. The hawks were gone, their blessing spent. He felt Mira’s hand find his shoulder. Rowan pressed against his side and made himself tall to match a height he did not yet have.

“Home,” Mira said. She opened the door.

And in they went, the old dog with the frost at his muzzle and the young one with the bell at his throat, and the woman who had carried promises in her pocket to where the valley could hear them. The house took them in with the ease of the familiar, floorboards greeting pawpads as if it had been rehearsed. The last light left the kitchen window, and when it moved, the bell in the shadows gave a small answering ring, as if memory itself had nodded.

Harlow settled in his spot and left half of it empty, not to give up, not to make space he didn’t want, but because sharing is how a room grows. Rowan curled into that offered curve without thinking. Mira knelt, pressed her palm to both of them at once, and didn’t speak, because there are vows you finish by breathing.

Outside, the valley rested. Inside, three heartbeats found the same time, and kept it.